In my previous post I stuck to ordinary Christian symbolism. The "Marseille" design and its prototypes might have produced, or been produced by, more erudite interpretations, discussed in humanist circles in the 16th-18th centuries. Here are a few possibilities.

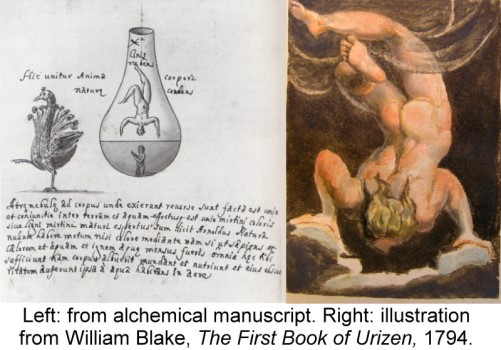

(1, alchemy.) One is suggested by a 16th century alchemical illustration, which seems to have been well enough known that William Blake used it in his depiction of the element Air in his "Book of Urizen," 1794. In this way of seeing the Noblet falling figure, he is rising from the water as vapor rather than, or as well as, falling as condensation. The alchemical figure may also have been an inspiration for some of Bosch's upside-down men in his "Garden of Earthly Delights," central panel, c. 1504 (details below)

The figures in the alchemical illustrations are usually in a container; the person on the card is not. However he may derive from a more general tradition, like the Bosch images, souls in an altered state, or the Blake image, floating upside-down. On the card, they touch the plants and the earth, as though seeing the world in a new way. Here is what Jodorowsky says (p. 222):

The figures are not in the middle of falling, quite the contrary. Their hair is yellow, the color of illumination, and they are touching the plants growing out of the ground with their hands. In reality, they are honoring the potential of the Earth. They have their heads at the bottom like The Hanged man of Arcanum XII because they are seeing the world in a new way. The intellect, the mind, is looking directly at Nature. One of the feet of one of the figures is pointed toward the sky; his steps are leading him to the mind.

The two imps of Arcanum XV have become humanized and have realized their ascent...

I see no reason why such thoughts, influenced then by alchemical illustrations, shouldn't have occurred to people in the mid-18th century as well.

(2, phallus; and 3, spinal column.) Another interpretation, suggested by Daimonax (

http://www.bacchos.org/tarothtm/15diable3.html), is an association between the smoke or flame coming out of the tower with the serpent coming out of the basket on Dionysian sarcophagi.

Clement of Alexandria said that what was in the basket on the tray represented the "virilia of Dionysus" (

Exhortation to the Greeks 2.15,

http://www.theoi.com/Georgikos/Zagreus.html). The object poking out of the basket on the Bateleur's table is thus a precursor to the tower of the Maison-Dieu. On the sarcophagi, the snake is then a symbol for the phallus of the god. In case one supposes that identifying snakes and phalli was too Freudian for the 17th century, I post on the right the Florentine Minchiate Devil card. From this perspective, sexual energy activated in the previous stage of the Devil card is now expressed as the fecundating power of the god, exploding heavenward.

On one level, this is the release of instinctual power. Thus Jodorowsky says of the card (p. 224)

The phallic connotation of the tower also makes it a symbol of the male sex organ and all the questions connected to ejaculation.

Such a perspective on the Tower would not have to await a Freud.

On a higher plane than the instinctual is the Hindu doctrine of the Kundalini as a serpent rising through the spinal column. This idea was certainly known to educated Europeans by the 18th century, and possibly by the 17th. The top of the tower would then be the head--and the "crown chakra"--which as the seat of the ego has been knocked off kilter by the energy coming up from below. Jodorowsky says, somewhat melodramatically (p. 223),

The diabolic androgynous being of Arcanum XV has become a flame that has climbed up the entire spinal column and opened the coronary nervous center to launch itself into the cosmos.

Jodorowky is not trying to be historical here, but I see no reason why similar thoughts would not have occurred to tarot interpreters and designers of the 17th-18th centuries.

(4, Dionysus and Pentheus.) There might be an association, suggested by Daimonax (

http://www.bacchos.org/tarothtm/15diable3.html), to Euripides' famous play

The Bacchae, where Dionysus's cousin Pentheus, not recognizing Dionysus, unknowingly locks him up, thinking him merely a priest of Dionysus, whose cult Pentheus suppresses because he does not believe Dionysus to be a god. Dionysus in disguise then calls on the "sacred lord of earthquakes" to destroy the palace, and adds, "Let fiery lightning strike right now, burn Pentheus' palace, consume it all." (

http://beauty.gmu.edu/AVT472/AVT472%20P ... -text).pdf). The palace appears to disintegrate and burn, and Dionysus walks out the prison door. This event is possibly paralleled on the card by the man on the steps--although the man is not shown walking. Dionysus then leads Pentheus to go into the mountains and climb a tree from which to view the secret rites of the Maenads. They discover him, and he dies at their hands--although not by falling; his death testifies to the power of the god against his detractors.

This interpretation, since there are several mis-correspondences between the card and the story (it's only a tower, not a palace, and the men don't take the positions on the card), is not specific enough to refer uniquely to Dionysus. It is simply one more instance (of which the Bible is full) of a god's punishment by natural calamity of those who do not honor him. However it is unlike many of them in that it also contains the element of freeing oneself, of bursting illusory fetters, such as bound the imps of the Devil card, and stepping out of his prison, just the kind of liberation of which Jodorowsky speaks.

(5, Dionysus and Ariadne at Argos.) Daimonax has applied Dionysus' next adventure, in which he tries to establish his cult in Argos, to the Devil card. I think it fits the Maison-Dieu imagery better. In the assault on Argos, its ruler Perseus kills Ariadne (here with a battalion of women) with his spear and throws a near-dead Dionysus into a lake (Apollodorus,

Library 2.3; Pausanias,

Guide to Greece, several places; Nonnus,

Dionysiaca 25.10. See

http://www.theoi.com/Olympios/DionysosM ... ml#Perseus). Near Argos is just such a lake, described by Pausanias as being an entrance to Hades, one that Hercules also used. Dionysus did go to Hades, according to many ancient accounts, to rescue his mother Semele (

http://www.theoi.com/Olympios/DionysosM ... Underworld). So perhaps Dionysus used the lake on this occasion, to rescue his wife as well as his mother. On this view Ariadne would be the one lying on the steps of the tower, and Dionysus the one falling into the water of the Noblet card. From this perspective the card represents a defeat requiring a metaphorical journey to the underworld and back. The Star and Moon cards, on this interpretation, are in the lands of the dead, as I have already spelled out in other posts. It is not clear what the Devil card would be, however--perhaps his return from India, corresponding to a stage of initiation in which the initiates are in shackles.

(6, Cambyses and Prexaspes.) In his

Histories, Book III, Herodotus tells of a King of Persia, Cambyses, and his confidante Prexaspes. The King, after conquering Egypt, killed the sacred Apis bull, aiming at the heart but piercing the thigh instead, after which it died slowly. Then Cambyses went mad. He had a vision of his younger brother taking power in his absence. So he had Prexaspes secretly kill the brother. Then he himself killed his sister, whom he had forced to live as his wife (all up to this point at

http://www.greektexts.com/library/Herod ... ng/54.html). Then word came that the younger brother had assumed the throne. The King, not in his right mind, mortally wounded himself with his own sword, in the same place on his body that he had killed the bull (

http://www.greektexts.com/library/Herod ... ng/63.html). Back in Persia, the confidante Prexaspes was ordered by the new rulers to vouch for the legitimacy of the king's successor, an impostor posing as the brother. Ordered to speak out his endorsement from a high tower, he denounced the imposture, confessed his murder of the brother, and jumped from the tower to his death (

http://www.greektexts.com/library/Herod ... ng/67.html).

Here we have two deaths, Cambyses' and the confidante's. Of the two, it is the one who jumped who has the greater possibility of redemption. As far as imagery relating to this story in the Noblet and other "Marseille I" designs, there might be Egyptian-Pharoah-style hats that have fallen off the two figures. In the "Marseille II," the water next to the tower might be a reference to the Nile, or perhaps Babylon. And of course there are the tower, the falling figure, and the figure on the ground.

I have not seen this association to the card anywhere in the literature. However the story was readily available in tarot circles. In fact, according to WorldCat, its first translator into Italian was Matteo Boiardo, late 15th century Ferrara, printed in 1533. He is otherwise known, of course, for composing a poem suggesting a unique tarot-style deck of cards. The first Latin translation of Herodotus's

Histories was published in 1499 Venice.

[Added by mikeh the next day: Later, in 1781, de Gebelin used Herodotus's

Histories in his interpretation of the Maison-Dieu card. Book 2, Chapter 121 (

http://old.perseus.tufts.edu/GreekScience/hdtbk2.html), has the story of two brothers who rob the Pharaoh's treasure chamber, using a hidden entrance, a movable stone installed by their father, who built the chamber. On their first trip, they carry out a large quantity of gold. But on their second try, one is caught in a a net trap and has to be beheaded by the other, so as to hide his identity; the other escapes with the gold and goes on to have more adventures, eventually marrying the Pharaoh's daughter. De Gebelin (

http://tarotpaedia.com/wiki/Du_Jeu_Des_ ... _de_Plutus) says that the card depicts the two brothers on their successful trip: "Ils voloient le Prince, & puis ils se jettoient de la Tour en bas: c'est ainsi qu'ils sont représentés ici," i.e. "They robbed the prince, and then they threw themselves from the tower, it is thus that they are represented here." But Herodotus says only, "So when he [the father] was dead, his sons got to work at once: coming to the palace by night, they readily found and managed the stone in the building, and took away much of the treasure." The implication is that they simply went out the hidden entrance with their loot. Nobody jumps.]

(7, obelisk; and 8, lighthouse.) The tower might have been compared to an obelisk, an object familiar to anyone who visited Rome or saw any of the numerous engravings done of the ones there. Most of them would have been the first object around to receive the rays of the sun, which its top would then reflect back and downwards. (The obelisk at St. Peter's, of course, would have been upstaged by the dome of the basilica, thus showing the greater power of Christianity.) They signal the coming end of night. As such the tower of trump XVI could be compared to the towers on the Moon card. As such, too, it could be compared to a lighthouse shining to lead our way, a comparison that Jodorowsky indeed makes (p. 224). In that context he re-imagines the little globes around the tower as well, not as fires of destruction but as configurations of energy leading us forward, just as star-constellations guide the sailor.