The versions of Jean Molinet (1425-1507), Jean Robertet's contemporary, should be added to this collection of the Latin quatrains and their French versifications.

Noël Dupire, ed., Les Faictz et Dictz de Jean Molinet, 1937, pp. 584-587.

https://archive.org/details/LesFaictzEt ... 1/mode/2up

As far as I can tell, Molinet's version had only two manuscript witnesses, in Tournai 105, which was apparently destroyed (in WW2 perhaps, I haven't researched it much), and in BnF Rothschild 471, f. 16v (c. 1520-1526), which retains only the first two, Love and Chastity. Dupire's edition thus remains the sole evidence we have of the whole series.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... 9/f39.item

I could be mistaken, since I haven't even begun to check the list of manuscripts Dupire gives in volume one of the Faictz et Dictz -

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5175q/f12.item

But A (Tournai 105) and C (J. de Rothschild 471) are the only two that he lists on page 584. Dupire's note "Voir Jean Molinet 125" refers to his book Jean Molinet - La Vie - Les Oeuvres (1932), page 125, of which I have only been able to see Google snippets. But he mentions those of Robertet as well,

https://books.google.fr/books?redir_esc ... =triumphes

and another author in the Rivista di letterature moderne e comparate, volume 34 (1981), p. 85, quotes Dupire:

"Au XVe siècle, il existait un abrégé [des Trionfi] en latin qui fut souvent mis en vers français: Jean Robertet traita le sujet en huitains et son fils François en rondeaux. Molinet en fit des sixains dans les Six triumphes en latin et franchois."

"In the 15th century, there was an abridgement [of the Trionfi] in Latin that was often put into French verse: Jean Robertet treated the subject in huitains and his son François in rondeaux. Molinet made sixains of it in the Six triumphes en latin et franchois."

https://books.google.fr/books?id=uF_kAA ... AF6BAgKEAI

Have we seen François Robertet's rondeaux?

Having looked around a bit now, it seems they have never been printed. None of the those I have seen so far include the Latin quatrains.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

152Thanks for the links, Ross. Aren't Francois's Rondeaux on pp. 473-479 of Douglas/Zsuppan's Critical Edition? He didn't write any Latin quatrains that I have heard of.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

153Ah yes, thank you! I had overlooked Douglas' transcription.mikeh wrote: 26 Oct 2023, 13:45 Thanks for the links, Ross. Aren't Francois's Rondeaux on pp. 473-479 of Douglas/Zsuppan's Critical Edition? He didn't write any Latin quatrains that I have heard of.

Well, that takes care of François Robertet.

So there are three versions of the Latin quatrains, one from at least 1447, and two French adaptations, by Jean Robertet and Jean Molinet.

Also there are three French adaptations, and probably other Latin and French in tapestries and stained glass.

I haven't checked all of these manuscripts, except for our well-known Français 24461:

https://portail.biblissima.fr/fr/ark:/4 ... 272b83881a

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

154Since Douglas says that Francois's rondeaux are simply paraphrases of his father's huitains, perhaps they are worth translating. Here is Douglas's transcriptions and what I come up with, with the major variants in brackets and leaving in French where I am afraid even to speculate. This is by no means an expert translation, just something that I hope suggests the general sense.

Comments: I notice that he goes back to Thetis rather than Tethys. But "repas" implies food, which comes from earth or sea. So he must have the goddess and the nymph confused.Triumphe de Cupido

SOUBZ Cupido sont prosternez les roys,

Et les coronnes soubz ses piedz et charrois,

Qui vont suyvant les voluptez et vices;

Grans et myneurs, jusques au plus novices,

[Jovis, Neptun, Pluton en leurs offices]

N‘en sont exemptz, tant soient fors et roidz.

Il n'est au monde si dangereux surcrois

[Au monde n'a si regretez surcroys]

D'honneurs et biens estre mis en descrois,

Comme l ’on voit souvent les folz et nices

Soubz Cupido.

Sceptres qui sont en sublimez conrois

Immoderez, tombent en désarrois;

Les moderez à regner sont propices.

Mettez donc frain, princes, à voz delyces.

Sans plus vivre en si piteulz arrois

Soubz Cupido.

Triumph of Cupid

UNDER Cupid are prostrate the kings,

And the crowns under his feet and car,

Who follow pleasures and vices;

Great and small, down to the most novice,

[Jovis, Neptun, Pluto in their offices]

Are not exempt, however strong and roitz [cold?].

There is no other place in the world that is so dangerous

[The world has so regretted excesses]

Of honors and goods being placed in decline,

As we often see the fools and naive ones

Under Cupid.

Scepters which are in sublime conrois [with kings?]

Immoderate, fall into disarray;

The moderates to reign are auspicious.

So put the bit, princes, to your pleasures.

Without living in such piteous array anymore

Under Cupid.

Triumphe de Chastité

Chastité vainc toute Amour furieuse;

Arc, pharetre et flambe impétueuse

De Cupido conculque et met au bas,

En le privant de plaisirs et d ’esbaz,

Comme dame puissante et vertueuse.

La personne repute bien heureuse

De l ’ensuyvir sans cesser envyeuse.

En temps de paix, de guerre et de débata

Chastité vainq.

Es delices de Cypre plantureuse

Est nourrye vye voluptueuse;

Mais de Ceres et Thetis les repas

Font refroidir et regler par compas

Effrenée jeunesse l'amoureuse;

Chastité vainq.

Triumph of Chastity

Chastity conquers all furious Love;

Bow, beacon and impetuous flame

Of Cupid tramples and puts at the bottom,

By depriving him of pleasures and esbaz [?],

As a powerful and virtuous lady.

The person is considered very happy

To follow her without ceasing to be envious.

In times of peace, war and debate

Chastity overcomes.

The delights of bosomy Cyprus

Is nourished and voluptuous life;

But of Ceres and Thetis the meals

Are made cool, and regulate by compass

Unbridled amorous youth;

Chastity overcomes.

Triumphe de la Mort

La Mort prent tout, sans espargner personne ;

Son hault povoir à cela se consonne

Qu'il n'est si chaste, qui ne perde la vye;

Quand il luy plaist, il fault que l'on desyve;

Chascun fait jou quand sa grand cloche sonne.

Où est celluy, pour avoir qu'on luy donne.

Tant soit il grand, à qui elle pardonne?

Il n'en est nul; quelque chose qu ’on dye.

La Mort prent tout.

Celluy vit sain qui point ne s'abandonne

Estre lubrique, Car qui trop s'y addonne,

A mille maulx s'expose et se desdye.

Par accident, fortune ou maladye,

Nully n'eschappe. Quand le Saulveur l'ordonne

La Mort prent tout.

Triumph of Death

Death takes everything, sparing no one;

Her high power in this is consonant

That there is no one so chaste who does not lose their life;

When it pleases her, we must desist;

Everyone plays when their big bell rings.

Where is the one, to have that given to him?

No matter how great, whom does she pardon?

There is none; nothing is kept.

Death takes all.

One lives healthy who does not abandon himself

To be lustful, For whoever indulges in it too much,

To a thousand evils is exposed and destroyed.

By accident, fortune or illness,

No one escapes. When the Savior orders it

Death takes all.

(Le Trlumphe de Bonne Renommée)

Par Renommée des memorables faictz

De ceulx qui furent jadis choisis et faictz,

Noz ancestres seans en haultz portoires,

Manifestez nous sont les inventaires

De leurs actes, jamais par Mort deffaictz.

En leurs gestes reluisent les effects

Tant des Homains, jà pieça putrefaictz,

Que d'autres mille, d'honneur les repertoires.

Par Renommée.

Ce firent ceulx qui soustindrent le faiz

Virilement contre les imparfaictz.

Et conquirent si loingtains territoires,

En leurs vieilz jours plains de loz meritoires.

Qui soubz marbre les rend clers et parfaictz,

Par Renommée.

(The Triumph of Good Renown)

By Renown of memorable deeds

Of those who were once chosen and done,

Our ancestors bore themselves high,

Show us the inventories

Of their actions, never by Death defeated.

In their gestures the effects shine

So many Humans, already putrefied a long time,

Than others a thousand, of honor the repertories.

By [or For] Fame.

These were the people who sustained deeds

Virilely against the imperfect.

And [who] conquered so distant territories,

In their old days full of meritorious loz [?].

Who under marble makes them clear and perfect,

By [or For] Fame.

Triumphe du Temps

Par traict de Temps tout chet en decadence;

Tout se passe sans nulle difference;

Il n'est chose que vieil Temps ne termine:

Renommée deperit et se myne,

Et si s ‘en perd entiere congnoissance.

Longuement vivre et avoir sa plaisance,

Auctorité, et biens en abondance,

Proufite peu, puisqu'il fault que tout fine.

Par trait de Temps.

Où sont les preux et tant de roys de France.

Qui decorerent leurs noms par leur vaillance?

Il n'en reste memoire ne cousine ,

Fors par escript qui les haultz faictz desine.

De leur renom, qu'on mect en obliance

Par traict de Temps.

Triumph of Time

By the emptying of Time, everything is in decline;

Everything passes [perishes] without any difference;

There is nothing that old Time does not end:

Renown wastes and digs away,

And so all knowledge of it is lost.

Live long and have pleasure,

Authority, and goods in abundance,

Profit little, since all must end.

By the emptying of [or by] Time.

Where are the brave ones and so many kings of France?

Who decorated their names with their valor?

There remains no memory of them,

Except by the writing which high deeds grant,

Of their reputation, which is honored

By the emptying of [or by] Time.

VIe Triumphe et dernier, de claire vision

[Le Dernier triumphe, de Eternité.

La Divinité parle.]

A tousjours mais en la gloire eternelle

Pardureront les estans soubz mon elle,

Car j‘ay en main, comme victorieuse.

La palme verte, florissant si heureuse

Que nulle chose la peult faire mortelle.

Au hault triumphe [trone] reluisant comme estoille.

Pardessus tout j’ay la puissance telle

Que je demeure royne tresglorieuse

A tousjours mais.

L'arc Cupide, son carcas, et sequelle

Pudicicie, Atropoz et ce qu'elle

A de pouvoir, Fama la vertueuse,

Et ce vieil Temps, ce n est chose doubteuse.

Deviendront rien; mais je suis immortelle

À tousjours mais.

VIth Triumph and last, of clear vision

[The Last Triumph, from Eternity.

The Divinity speaks.]

Forever and ever in eternal glory

Endure the estans {estates?] under my her [feet?],

Because I have it in hand, as victorious.

The green palm, flourishing so happily

That nothing can make her mortal.

At the top the triumphs [throne] shining like stars.

Above all I have the power

That I remain a very glorious queen

Forever and ever.

Cupid's bow, its cadaver, and sequel

Pudicicie, Atropos and that which

Has power, Renown the virtuous,

And this old time, it is not a doubtful thing,

Will become nothing; but I am immortal

Forever and ever.

Last edited by mikeh on 06 Nov 2023, 10:54, edited 1 time in total.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

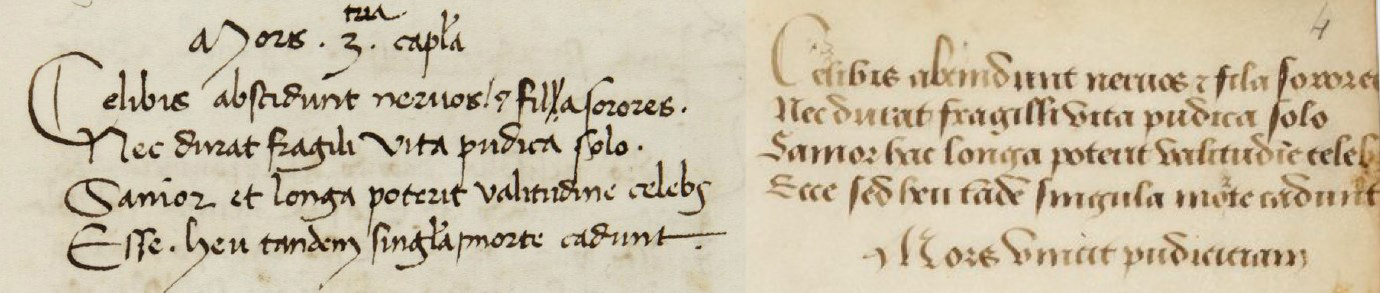

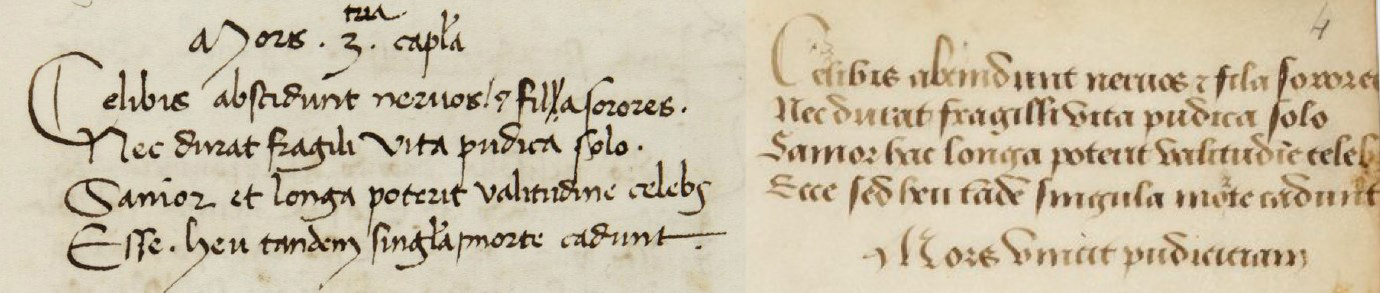

155It is interesting that the only difference between U.07.24 and Robertet in the Death triumph is in the fourth line, where the former reads "Esse. Heu" and the latter reads "Ecce sed heu."

U.07.24 would mean:

Celibis abscidunt nervos et fila sorores,

Nec durat fragili vita pudica solo.

Sanior et longa poterit valitudine celebs

Esse, heu tandem singula morte cadunt.

The sisters sever the nerves and threads of celibacy,

Nor does a chaste life endure on the fragile ground.

Healthier and in long-lasting soundness the celibate will be able

To be; alas, they fall one by one in death.

Robertet would mean

Celibis abscidunt nervos et fila sorores,

Nec durat fragili vita pudica solo.

Sanior et longa poterit valitudine celebs

Ecce sed heu tandem singula morte cadunt.

The sisters sever the nerves and threads of celibacy,

Nor does a chaste life endure on the fragile ground.

The celibate may be able to be healthier and in long-lasting soundness,

But behold, alas! they fall one by one in death.

Which version sounds more "correct"? It seems to me that the "esse" of U.07.24 doesn't really need to be there, so this reinforces the sense that this is a copy of another text, and, in this scenario, that it was a manuscript in which either the "ecce" was written indistinctly enough that it resembled an "esse", or that the manuscript of these pomes that U.07.24 was copied from itself contained the error.

The only way I can imagine an ecce being confused for an esse is if the manuscript was in a very small and cramped style, and that the scribe wrote the letter s with no descender, and only slightly ascending. In the case of this word it must have been very indistinct.

This doesn't address Robertet's "sed." My sense is that it is more likely for a copyist to omit a word than to add another, so that Robertet's source corresponded more closely to the original than U.07.24 does.

I can't tell if the scansion gives a better way to judge the greater authenticity of one or the other version.

U.07.24 would mean:

Celibis abscidunt nervos et fila sorores,

Nec durat fragili vita pudica solo.

Sanior et longa poterit valitudine celebs

Esse, heu tandem singula morte cadunt.

The sisters sever the nerves and threads of celibacy,

Nor does a chaste life endure on the fragile ground.

Healthier and in long-lasting soundness the celibate will be able

To be; alas, they fall one by one in death.

Robertet would mean

Celibis abscidunt nervos et fila sorores,

Nec durat fragili vita pudica solo.

Sanior et longa poterit valitudine celebs

Ecce sed heu tandem singula morte cadunt.

The sisters sever the nerves and threads of celibacy,

Nor does a chaste life endure on the fragile ground.

The celibate may be able to be healthier and in long-lasting soundness,

But behold, alas! they fall one by one in death.

Which version sounds more "correct"? It seems to me that the "esse" of U.07.24 doesn't really need to be there, so this reinforces the sense that this is a copy of another text, and, in this scenario, that it was a manuscript in which either the "ecce" was written indistinctly enough that it resembled an "esse", or that the manuscript of these pomes that U.07.24 was copied from itself contained the error.

The only way I can imagine an ecce being confused for an esse is if the manuscript was in a very small and cramped style, and that the scribe wrote the letter s with no descender, and only slightly ascending. In the case of this word it must have been very indistinct.

This doesn't address Robertet's "sed." My sense is that it is more likely for a copyist to omit a word than to add another, so that Robertet's source corresponded more closely to the original than U.07.24 does.

I can't tell if the scansion gives a better way to judge the greater authenticity of one or the other version.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

156Nathaniel's translation of suppeditatur (3rd person singular present passive indicative of suppedito; "amor" is the direct object, i.e. "love is abundantly supplied, provided") also stumped me. None of the standard dictionaries, including the Lewis and Short and the Gaffiot on my shelf, give any meaning but "sufficiently provided", "abundantly supplied", and that sort of semantic range. The online Thesaurus Linguae Latinae hasn't yet gotten up to the letter S https://thesaurus.badw.de/tll-digital/t ... ccess.htmlmikeh wrote: 25 Oct 2023, 00:23

Now Pudicizia:Very similar, at least, and again seeming to explain an image. About "nec" vs. "et" in the third line, it seems to my ignorant mind that it depends on what "supeditatur" means. Wiktionary says "supplied"; but Nathaniel's "crushed" (with "et") would certainly be more evocative. But I don't see it. Nathaniel. You write:Pudicita capitulum unum

Arma pudicicie superando cupidinis arcum,

Hic dominum calcant, et sua tela premunt.

Nec pingui Cipro, nec molli floribus Yda,

In Cerere et Theti suppeditatur amor.

Arma Pudicicie superando Cupidinis arcum

Et dominum calcant, et sua membra premunt.

Nec pingui Cipro, nec mollis floribus Yde

In Serere et Theti supeditatur Amor.

Pudicicia vincit Amorem.

L’arc Cupido a esté surmonte [surmonté?]

Par les armes de Dame Chasteté,

Qui ce seigneur conculque et tient en presse

Et ses membres trop rebellans oppresse.

Car es [les?] delices de Cypre l’opulente,

Ne [ni?] es [les?] fleurs souefves d'Yde Amour n'est pas lente;

Mais par Seres et Tethis refrenée

Est folle Amour et challeur forcenée.

Chasteté vainc Amour.

Vinco Pudicicia armatos ego inermis Amores ^ ^

Et sine me virtus non placet ulla dies

Arms of Chastity overcoming Cupid's bow

And they trample the master, and his limbs [his darts] press

[With] Neither the lush Cyprus, nor the soft flowers of Ida

In Ceres and Thetis, is Love supplied.

Chastity overcomes love.

Cupid's bow has been overcome

By the arms of Lady Chastity,

Who tramples on this lord and keeps [him] in press

And his too rebellious members oppress.

For neither the delights of opulent Cyprus,

Nor the soft flowers of Ida, is Love slow;

But by Ceres and Tethis restrained

Is crazy Love and frenzied heat.

Chastity defeats Love.

I conquer defenseless Loves armed with chastity

And without me virtue does not please any day. [??]

Well, it all depends on the meaning of "suppeditatur". I don't understand how it can mean "crushed".Robertet's translation of the quatrains is quite flawed. He makes several errors, no doubt due to the fact that the Latin of the quatrains is almost purely classical, to an impressive degree for the time—their author must have been quite thoroughly steeped in the works of Roman poets such as Virgil—whereas Robertet's own Latin was strictly medieval, as can be seen in his few surviving Latin works. There were several word meanings and phrases that he simply didn't grasp.

But his misunderstanding was not entirely his fault in one instance, at least. In both the Modena copy and in the manuscript he used, the wording of Chastity has what appears to be a miscorrection in the third line, which renders the last two lines of the stanza nonsensical. This is the "Nec ... nec", which must surely have originally been "Et ... et".

If this were so, those last two lines could be translated as "Both on lush Cyprus and on amorous Ida with its pleasant flowers—on both land and sea—Love is crushed underfoot." This was evidently the poet's take on the objects held in Chastity's hands: he chose to associate the palm frond with the isle of Cyprus and the sea, and the sprig of leaves and flowers with Mount Ida and land.

Otherwise, there is the substitution of the water-goddess Tethis for the victim of Zeus Thetis. This substitution makes little difference: with Tethis and Ceres, the idea of water vs. land is conveyed, as Nathaniel says; with Thetis and Ceres, the idea would be two victims of Zeus's lust, here attributed to the arrows of Cupid.

"Cerere" can be dative or ablative, but "Theti" can only be ablative (the dicitionaries give it as an alternative ablative form, normally "Thetide"), and the preposition "in" can only take the accusative or ablative in any case. Finally, "molli" is singular, while "floribus" is plural, so molli qualifies Ida (ablative), not the flowers. Robertet's version has "mollis Id(a)e", changing it to the genitive, "nor of/out of/from the flowers of pleasant Ida," but it doesn't affect the sense in any way that I can see. The following translation is an unpolished suggestion:

Overcoming the bow of Cupid, the arms of Chastity

Here trample their master, and impose their own weapons.

Neither with lush Cyprus, nor with pleasant Ida's flowers,

Is love supplied in matters of Ceres and Thetis.

I don't see a basis for Nathaniel's suggested emendation, even if the figures of Ceres and Thetis must be interpreted with some erudition.

Here are some of my thoughts:

Perhaps Ceres and Thetis (water) are “food and drink,” thus “nourishment.” In Cupid's case, the nourishment of sensual stimulation.

Perhaps the allusion is to the motherly love of Ceres for Triptolemus and Thetis for Achilles. This is not sensual love, but the “tough love” of forging character by hardship. Ceres nurses Triptolemus with milk by day, but at night puts him in the fire to inure him to hardship; Thetis does the same thing to Achilles (the Achilleid of Statius (text known to Dante) says that she tried to make him invulnerable by dipping him the river Styx (except for the heel by which she held him, hence the story of his only vulnerability). So this sort of love could be an allusion to becoming invulnerable to the desires of the flesh.

Ceres and Thetis nourish a kind of love higher than desire and sensual pleasure, that of motherly love.

Perhaps another allusion is to the rites of Ceres on Cyprus told in Ovid, Metamorphoses X.431-435, in which the pious mothers abstain from sex and all touch of man for nine days. An irony lies in the association of the island with Venus.

A similar irony may associate Thetis with Mount Ida, since it was on this mountain that Venus seduced Anchises, thus conceiving Aeneas. In Aeneid IX, 77-106, Aeneas' ships were made from wood of Mount Ida, and when the fleet, still moored, came under threat of burning from Turnus' attack, the ships turned into sea-nymphs, diving like dolphins dive, reappearing “in maiden forms.” They were able to do this because Jove promised to turn them into “Goddesses of the sea, like Nereus' daughter...”. Jove did this because of his mother Cybele's entreaties to protect the wood of the ships, made from her forest on Mount Ida.

In any case, both Ceres and Thetis were known best for their motherly roles.

I did find one dictionary of "new Latin" that gives the meanings of "subdued" and "defeated" to suppedito, J. Ramminger, "suppedito", in Neulateinische Wortliste. Ein Wörterbuch des Lateinischen von Petrarca bis 1700,

URL: www.neulatein.de/words/0/005128.htm (benutzt am / used on 25.10.2023)

http://nlw.renaessancestudier.org/words ... 005128.htm

unterwerfen, means to subdue, subjugate, conquer; and besiegen means to beat, conquer, defeat, overcome.suppedito, -are, -aui – unterwerfen, besiegen: PAVL CROSN carm ed. Kruczkiewicz p.26 Hic hostis potuit nancisci bella cruentus | Prospera et egregios suppeditasse viros, | Ni rex magnanimus fraudes sensisset iniquas. == carm ed. Kruczkiewicz p.45 Atque sub incesto nullum durare pudorem | Rege et honestatem suppeditare probrum.

As you can see, Ramminger cites only one poet, Pawel z Krosna (1474-1517), in -

Pauli Crosnensis Rutheni atque Ioannis Visliciensis carmina, Cracow, 1887, p. 26

https://books.google.fr/books?id=56gTAA ... 22&f=false

The passages are:

Quem sic certantem proprii mirantur et hostes,

Miraturque alto Iuppiter ispe polo.

Hic hostis potuit nancisci bella cruentus

Prospera et egregios suppeditasse viros,

Ni rex magnanimus fraudes sensisset iniquas

Firmassetque suis agmina sparsa tonis,

Et nisi militibus stimulos iecisset amaros,

Mansissent illo milia multa loco.

"Those whom his own men and enemies alike admire as they see him fighting in such a manner,

And even mighty Jupiter himself admires from the high heavens,

This enemy could have found bloody wars and subdued (or defeated) excellent men,

If the generous king had not perceived deceitful tricks

And had not strengthened his scattered forces with his own measures,

And if he had not driven bitter spurs into the soldiers,

Many thousands would have remained in that place."

Kruczkiewicz notes the word "suppeditasse" specifically -

Aut poetae error aut mendum typographi huic voci subesse videtur. Desiderantur fere haec “perdere fraude.”

"It seems that there is either an error by the poet or a typographical mistake in this passage. These are almost always desired after 'to defeat by deceit."

I'm not sure what to make of the second part, what is "desiderantur" that is, but he means that Krosna used the word wrongly or that it is a typographical mistake somehow.

The second passage, on page 45, seems to use it correctly, as far as I can understand it:

Verum ubi virtutem su iniquo principe nullam

Sentiret tutam vel iuvenile decus,

Atque sub incesto nullum durare pudorem

Rege et honestatem suppeditare probrum,

Illius et populum passim damnare misellum

Audiret miseris facta nefanda modis,

Castigat clara sceleratum voce tyrannum

Terruit et saevis terque quaterque minis,

Scilicet ut coepto iamiam cessaret iniquo

Disceret et verae nosse salutis iter.

"But when he felt that there was no safe virtue in an unjust ruler,

And that youthful honor could find no protection,

And under a wicked king, no sense of shame could endure,

Nor could the good provide honour;

And he would hear of the wretched people suffering everywhere,

The unspeakable deeds inflicted on them in miserable ways,

He rebukes the wicked tyrant with a clear voice, branded with crime,

He terrifies him with fierce threats, thrice and four times,

So that, surely, he would now cease his unjust beginning,

Learn the path of true salvation."

Kruczkiewicz notes the word again here, referring to his previous note on page 26. I don't know if "nor the good to defeat honor" makes more sense, even if the meaning of the passage is clear in general.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

157Thanks, Ross. I was wondering what to do with the ablative. Just to complicate things - or maybe simplify in the end - there are also Jean Molinet's quatrains.

For Love, here is Molinet's quatrain:

So now Chastity. Here is Molinet:

It seems worth putting a tentative translation of Molinet after the ca. 1447 (in Ross's translation, except that I read "sua" as "her" instead of "their own") followed by their French versions:

If Ceres' abstinent rites are on Cyprus, that restraint counteracts Venus (and Love) there. Likewise, Thetis (going with the quatrains) with Achilles has a restrained love, if it entails putting him in a fire; but that was not a restraint on "crazy love". Pelleus had to restrain Thetis in order to get her to marry her. But that is not a restraint against "crazy love". The prophecy that Thetis's son would someday be more powerful than his father restrained Zeus from violating her. That last, it seems to me, comes the closest to restraining "crazy Love and frenzied heat."

There is also Francois Robertet's paraphrase about Ceres and "Thetis" (correcting his father, or his scribes):

Now Death. Molinet's quatrain:

I understand that "fragili" is ablative or dative. Couldn't it still modify "vita", i.e. "life concerning fragility"? The point is that chastity does not endure, in the sense of being subject to death.

Neither Robertet has anything like that line of the quatrain, that I can find.

I'll get to the other three triumph-summaries later, adding Molinet to the others and looking at the quatrains from the perspective of the French.

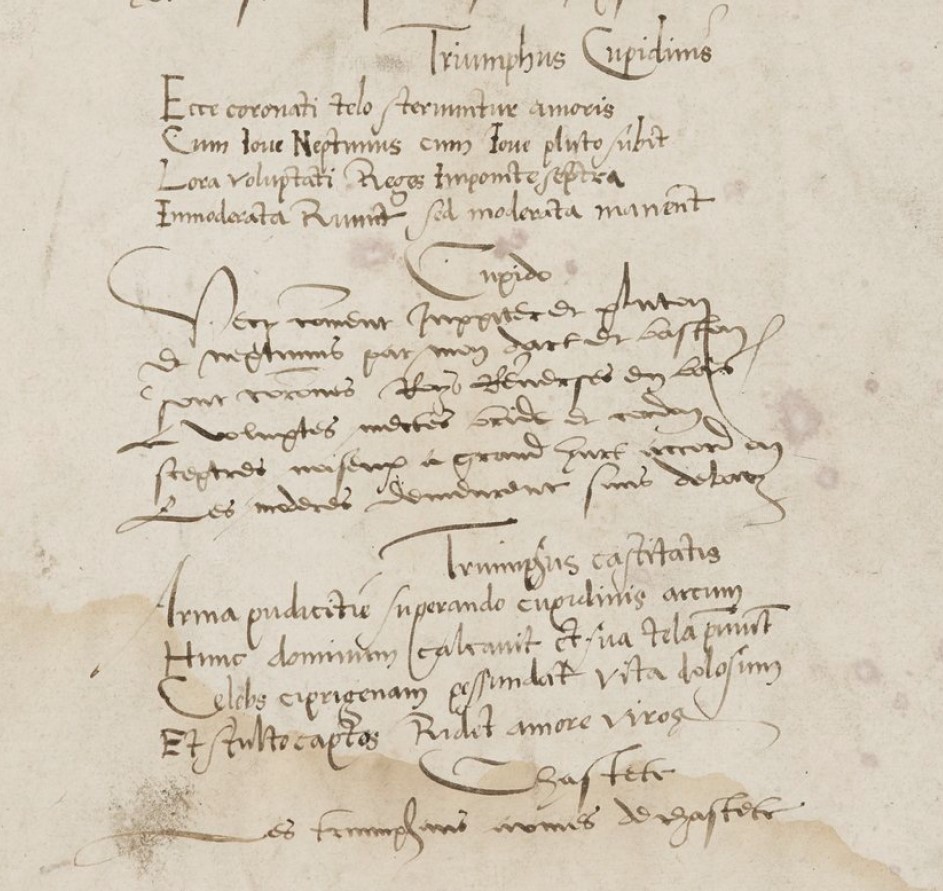

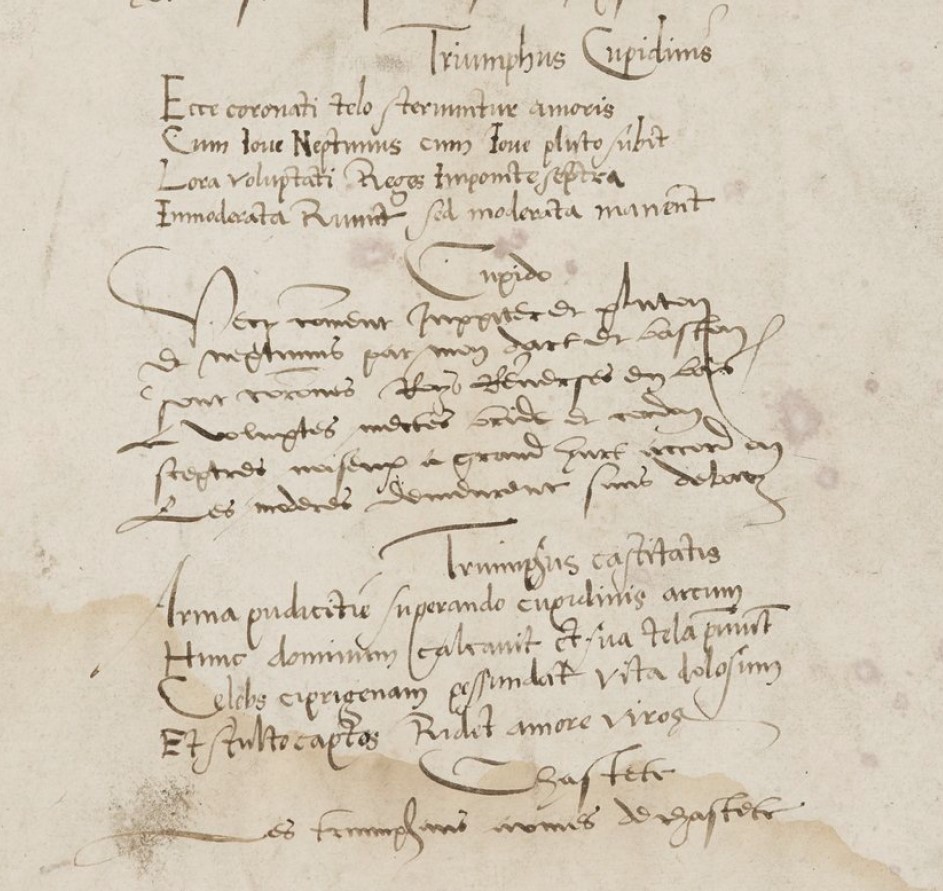

For Love, here is Molinet's quatrain:

For comparison, here are the ca. 1447 and Robertet:Ecce coronati telo sternuntur amoris,

Cum Jove Neptunus, cum Jove Pluto subit;

Lora voluptati, reges, imponit; sceptra

Immoderata ruunt, sed moderata manent.

We can also compare the French, Molinet first, then Robertet:Ecce Coronati telo sternuntur amoris.

Cum Iove neptunus cum Iove pluto subit.

Lora voluptati reges imponite sceptra

Immoderata ruunt et moderata manent.

Ecce coronati telo sternumtur Amoris

Cum Iove Nettunus, cum Iove Pluto subit.

Lora voluptati reges imponite: septra

Immoderata ruunt et moderata durant.

ca. 1447: Reins to pleasure kings put [imperative] scepters

Uncontrolled rush and controlled stay.

Robertet: Reins to pleasure kings put: scepters

Uncontrolled rush and controlled endure.

Molinet: Reins to pleasure, kings, put: scepters

Uncontrolled rush but controlled stay.

Jean Robertet:Vecy comment Jupiter et Pluton

Et Neptunus, par mon dart et bâton,

Ont couronnés roix, reversés en bas ;

A volupté mettés bride et cordon;

Sceptres noiseux a grand hurt accorde on:

Les modérés demeurent sans debas.

Here is how Jupiter and Pluto

And Neptune, by my dart and staff,

have crowned kings, reversed to the bottom;

To pleasure put bridle and reins;

Agitated scepters to great hurt [?] are accorded:

The controlled remain without lowering

These French versions are essentially the same. It seems to me that the last line of the ca. 1447 is ambiguous: it could mean either, the uncontrolled scepters rush and stay controlled," meaning that they stay controlled by Cupid, or "the uncontrolled scepters rush and the controlled stay," meaning that kings with self-control stay in power. Both Molinet and Jean Robertet assume the second interpretation. But perhaps the previous line, "princes, put the bit to your pleasure," suggests the alternative of self-control. I am wondering: has Molinet's French been modernized? In any case, I see that I made several mistakes translating the Latin earlier (e.g. I used Esperanto's definition of "imponite" instead of Latin's, just below it). The punctuation was very helpful.Cupido a de son dart prosternez

Jovis, Neptunne et Pluton couronnez,

Roys ensuivans folle amour et plaisance,

D’eulx triumphant nonobstant leur puissance.

Princes, mettez frain a voz voluptez,

Car les ceptres qui sont immoderez

Tumbent tantost et ne sont point estables;

Les modérez sont fermes et durables.

Cupid has his dart prostrate

Jove, Neptune and Pluto crowned,

Kings following [?] mad love and pleasure,

On them triumphant despite their power.

Princes, put the bit to your voluptuousness,

For the scepters that are uncontrolled

Sometimes collapse and are not at all stable;

The controlled are firm and durable.

So now Chastity. Here is Molinet:

In comparison, the ca. 1447 and Robertet:Arma pudicitiae superando Cupidinis arcum

Hunc dominum calcant et sua tela premunt;

Celebs Ciprigenam pessumdat vita dolosam

Et stulto captos ridet amore viros.

The c. 1447 has "Hic" where Robertet has "Et" and Molinet "Hunc", which is just "hic" in the accusative. Both the ca. 1447 and Molinet have "tela." Roberter has "membra." But then the c. 1447 and Robertet are the same, and Molinet rather different, less puzzling, except (for me) the word "Ciprigenam". Given how similar Molinet's first two lines are to the c. 1447, he seems to know that version. Perhaps, because the last two lines are so obscure, he is putting in something for them that he finds intelligible.Arma pudicicie superando cupidinis arcum,

Hic dominum calcant, et sua tela premunt.

Nec pingui Cipro, nec molli floribus Yda,

In Cerere et Theti suppeditatur amor.

Arma Pudicicie superando Cupidinis arcum

Et dominum calcant, et sua membra premunt.

Nec pingui Cipro, nec mollis floribus Yde

In Serere et Theti supeditatur Amor.

It seems worth putting a tentative translation of Molinet after the ca. 1447 (in Ross's translation, except that I read "sua" as "her" instead of "their own") followed by their French versions:

And Robertet's French:Ca. 1447: Overcoming Cupid's bow, the arms of Chastity

Here trample their master, and impose her weapons.

Neither with lush Cyprus, nor with pleasant Ida's flowers,

Is love supplied in matters of Ceres and Thetis.

Molinet: The arms of Pudicitia overcome Cupid's bow

Here trample the lord and impose her weapons;

Celibates Ciprigenam [?] put to the bottom [?] the deceitful life

and laugh at the foolish captives of love.

Lines 5 and 6 suggest, as Nathaniel says, that Cyprus and Ida are supposed to be erotic; and as you say, Mt. Ida as well as Cyprus are associated with Venus. Lines 7 and 8 are about the restraint of "crazy Love." "Neither/nor" fits the context, even if they're not actually there.L’arc Cupido a esté surmonte

Par les armes de Dame Chasteté,

Qui ce seigneur conculque et tient en presse

Et ses membres trop rebellans oppresse.

Car es [les?] delices de Cypre l’opulente,

Ne [ni?] es [les?] fleurs souefves d'Yde Amour n'est pas lente;

Mais par Seres et Tethis refrenée

Est folle Amour et challeur forcenée.

Chasteté vainc Amour.

Cupid's bow has been overcome

By the arms of Lady Chastity,

Who tramples on this lord and keeps [him] in press

And his too rebellious members oppress.

For [neither] the delights of opulent Cyprus,

Nor [?] the soft flowers of Ida, is Love slow;

But by Ceres and Tethis restrained

Is crazy Love and frenzied heat.

If Ceres' abstinent rites are on Cyprus, that restraint counteracts Venus (and Love) there. Likewise, Thetis (going with the quatrains) with Achilles has a restrained love, if it entails putting him in a fire; but that was not a restraint on "crazy love". Pelleus had to restrain Thetis in order to get her to marry her. But that is not a restraint against "crazy love". The prophecy that Thetis's son would someday be more powerful than his father restrained Zeus from violating her. That last, it seems to me, comes the closest to restraining "crazy Love and frenzied heat."

There is also Francois Robertet's paraphrase about Ceres and "Thetis" (correcting his father, or his scribes):

Here, yes, Ceres is food and Thetis drink - but not of Bacchus and whoever the god of banquets is, but rather of a restraining nature. But neither he nor his father explain what it is about Thetis and Ceres that make for restraint. Now Molinet:Mais de Ceres et Thetis les repas

Font refroidir et regler par compas

Effrenée jeunesse l'amoureuse;

But of Ceres and Thetis the meals

Make cool and regulate by compass

Frenzied youth, amorous.

So "Cyprigenam" has something to do with Venus, as we suspected. "Genam" means "cheek, eye socket, eye, eyelid" according to Wiktionary. That doesn't really fit. Maybe it's a copyist's error for some odd Latin ending, and it just means "Venus". If so, the "honest" celibates put her deceitful life on the bottom. The part about laughing and Venus losing her beauty would seem to be Molinet's invention, although mockery is a kind of restraint.Les triumphans armes de Casteté

Tiennent soulx pieds le régné et potesté

De Cupido et l’art qui sos affolle;

Honneste vie a tel auctorité

Dessus Venus qu’elle pert sa beaulté

Et rit, quand voit gens happés d'amours folle.

The triumphant weapons of Chastity

Hold under their feet the reign and power

Of Cupid and the art that sos [?] maddens;

Honest life has such authority

Above Venus that she loses her beauty

And laughs when she sees people caught up in crazy love.

Now Death. Molinet's quatrain:

And the other two, c. 1447 first:Celibis abscindunt nervos et fila sorores

Nec durât fragili vita pudica solo;

Sanior et longua poterit valitudine celebs

Esse, sed heu ! tandem singula morte cadunt.

Oddly, Molinet has the "esse" of the c. 1447 and the "sed" of Robertet. I don't know what to make of it. So the translation would be:Celibis abscidunt nervos et fila sorores,

Nec durat fragili vita pudica solo.

Sanior et longa poterit valitudine celebs

Esse, heu tandem singula morte cadunt.

Celibis abscindunt nervos et fila sorores

Nec durât fragilli vita pudica solo

Sanior hac longa poterit valitudine celebs

Ecce, sed heu tandem singula morte cadunt.

Here is the French:The sisters sever the nerves and threads of celibacy,

Nor does a chaste life endure on the fragile ground.

Healthier and in long-lasting soundness the celibate will be able

To be; But alas, they fall one by one in death.

This would suggest that he reads "Nec durât fragili vita pudica solo" as "Nor does fragile pudic life maintain a lasting foundation."Par les trois soeurs aians grifz afillés

De Chasteté sont rompus les fillés,

Qui est moult frelle et n’a fondement fin;

Et s’elle est saine et ses jours sont doés

De vie longue, ilz seront desnoés,

Car il n’est riens que

Mort ne mette a fin.

By the three sisters aians [by years?} grifz [?] afillés [affiliated?]

Of Chastity, are broken the fibers [?],

Who is very fragile and has no fine [?] foundation;

And if she is healthy and her days are blessed

Of long life, they will be lost,

Because there is nothing that

Death does not put to an end.

I understand that "fragili" is ablative or dative. Couldn't it still modify "vita", i.e. "life concerning fragility"? The point is that chastity does not endure, in the sense of being subject to death.

Neither Robertet has anything like that line of the quatrain, that I can find.

I'll get to the other three triumph-summaries later, adding Molinet to the others and looking at the quatrains from the perspective of the French.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

158Great work, Mike! I think these three witnesses alone are not enough to establish what the original text might be, although U.07.24 clearly has priority, but must be itself a copy. Robertet has the vincits (Nathaniel's term is great), but neither U.07.24 nor Molinet does. This could be the choice of both authors, or an indication that the sources of both didn't have them either. It is just too sparse a group to allow us to deduce the whole chain of transmission.

On Molinet's Amor, you've miscopied the printed source, which also has "imponite" in the third line. The only manuscript source I know, BnF Rothschild 471, folio 16v, shows the spelling:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... 9/f39.item

These are the only quatrains and French versions preserved in the manuscript, the other pages having been lost.

"You kings, rein in your pleasure; for wild scepters

fall, while those restrained, endure."

On Molinet's Amor, you've miscopied the printed source, which also has "imponite" in the third line. The only manuscript source I know, BnF Rothschild 471, folio 16v, shows the spelling:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... 9/f39.item

These are the only quatrains and French versions preserved in the manuscript, the other pages having been lost.

My attempt for good English idiom, while retaining as much literal sense as possible, is:mikeh wrote: 28 Oct 2023, 12:49 Thanks, Ross. I was wondering what to do with the ablative. Just to complicate things - or maybe simplify in the end - there are also Jean Molinet's quatrains.

For Love, here is Molinet's quatrain:For comparison, here are the ca. 1447 and Robertet:Ecce coronati telo sternuntur amoris,

Cum Jove Neptunus, cum Jove Pluto subit;

Lora voluptati, reges, imponit; sceptra

Immoderata ruunt, sed moderata manent.Ecce Coronati telo sternuntur amoris.

Cum Iove neptunus cum Iove pluto subit.

Lora voluptati reges imponite sceptra

Immoderata ruunt et moderata manent.

Ecce coronati telo sternumtur Amoris

Cum Iove Nettunus, cum Iove Pluto subit.

Lora voluptati reges imponite: septra

Immoderata ruunt et moderata durant.

ca. 1447: Reins to pleasure kings put [imperative] scepters

Uncontrolled rush and controlled stay.

Robertet: Reins to pleasure kings put: scepters

Uncontrolled rush and controlled endure.

Molinet: Reins to pleasure, kings, put: scepters

Uncontrolled rush but controlled stay.

"You kings, rein in your pleasure; for wild scepters

fall, while those restrained, endure."

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

159About "imponit", I'm not sure what you mean. If you are referring to the comma before and semicolon after, they are in the printed source. I suspected that they were the modern editor's addition but didn't have the ms. version to compare to. Thanks for that. And yes, "ruunt" would have been understood by the French writers as meaning "fall" rather than "rush," "fall" corresponding to Robertet's "tumbent" and Molinet's "a grand hurt" (I guess). I missed that. I was thinking of rushing, another meaning of "ruunt," as opposed to staying still. "Noiseux" would be "quarrelsome" rather than "agitated".

Now Fame. The Latin is identical to the ca. 1447, without Robertet's mistaken "sit" instead of "scit" (and assuming that "limpida" is right; the word on the page looks more like "melita," which is not a word, as far as I can determine).

Here is Molinet's French, reading "pallus" as "palus":

Robertet has a similar interpretation of the lake, as that of forgetting, oblivion = hell. And he somehow has read the "sit" of his quatrain as "knows" (or more precisely, "had known") - suggesting that the "sit" was simply a scribal error:

For Time, the Latin quatrain has in part different wording from the others, and I think easier to translate (although I am not sure about "sera"):

The quatrains in c. 1447 and Robertet go:

In the last triumph, the quatrain is the same as the others, but leaving out the word "abibunt", which the editor has inserted, I assume from the c. 1447. and not Robertet's "adibunt", which is a misspelling or typo.

Added later: I see from Douglas's critical edition (p. 74) that a later copy (BnF Fr. 1717) substitutes "mansion" for "mention." In that case "mention" is probably an archaic version of "mansion," or a scribal error, and the "my" refers simply to the personified Eternity and not the Virgin. The sense of "mansion" corresponds to Molinet's "hostel."

I think my efforts this time are better than before, but there were still things that didn't quite make sense, and I'm sure there's room for improvement.

Now Fame. The Latin is identical to the ca. 1447, without Robertet's mistaken "sit" instead of "scit" (and assuming that "limpida" is right; the word on the page looks more like "melita," which is not a word, as far as I can determine).

I am unsure about the last line. "Fama" and "lacus" are both nominative. And Lethe is not a lake, basin, or resevoir. So "Nor does clear lake Fame know of Lethe" is possible, I suppose. But it is not how our two Frenchmen read it.Omnia mors mordet, sed mortem fama triumphat.

Cetera mordentem, sub pede fama premit,

Egregium facinus post mortem suscitat ipsam

Nec scit Letheos limpida fama lacus.

Death devours all, but fame triumphs over death.

The rest devoured, fame presses underfoot,

A great deed alone raises after death

Nor knows clear fame of the lake of Lethe.

Here is Molinet's French, reading "pallus" as "palus":

Here the subject is "fine Renown", the same as in the Latin. "Suscitant" suggests the heads poking up from below of BnF Fr. 594 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Petr ... 4-fame.jpg). The Old French "scet" is a direct descendant of the Latin "scit," so he is following the c. 1447 or similar (as opposed to Robertet, who has "sit"). He substitutes "infernaux" for "Letheos," a wise move, if not entirely faithful.Mort chascun mort, mais Renommee fine

Triumphe sus Mort, qui vivans affine

Et presse au pied tous mordans dissolus;

Mais noble faict après mort, s’il est digne,

Va suscitant la renommee insigne,

Ne scet que c’est des infernaux pallus.

Death devours everyone, but fine Renown

Triumphs over Death, which living [?] refines

And presses underfoot all corrosive dissolutes;

But noble deed after death, if it is worthy,

Serves resuscitating [to resuscitate} distinguished renown,

Nor does it know that it is [it to be?] of the infernal swamp.

Robertet has a similar interpretation of the lake, as that of forgetting, oblivion = hell. And he somehow has read the "sit" of his quatrain as "knows" (or more precisely, "had known") - suggesting that the "sit" was simply a scribal error:

Qu'après leur mort de leur fait soit mémoire.

Inclite Fame n'eust jamais congnoissance

De Letheus, le grant lac d'oubliance.

Let their deed be remembered after their death.

Illustrious Fame had never known

Of Letheus, the great lake of forgetting [oblivion].

For Time, the Latin quatrain has in part different wording from the others, and I think easier to translate (although I am not sure about "sera"):

Here is Molinet's French:Post bustum quamvis ma net inclita fama superstes,

Hanc tamen exstinguant tempora sera licet ;

Quid prodest igitur nunc gloria, fama sepulto ?

Tandem comimpet hanc quoque tempus edax.

After the grave, although a clear [?] illustrious Fame may survive,

Yet time is permitted to slowly extinguish this;

What good, then, is glory now, when fame is buried?

Finally, this voracious time also comes to an end.

I assume "pasmee" means the same as "pâmée" with a circuin modern French.Combien qu’aprés Mort fiere et mal aimee

Demeure au siecle inclite Renommee,

Le Temps fort long l’estainct et sy l’efface.

Que poeult valloir gloire vaine et pasmee

Au mort bouté en tombe bien lamee,

Puisque le Temps corrumpt et corps et face?

However many centuries after proud and unloved Death

Remains illustrious Renown,

A very long Time destroys and effaces it.

What worth then can [?] glory vain and rapturous [?] be

To a dead man pinned in a well-laid tomb,

Since Time corrupts both body and splendor[?]?

The quatrains in c. 1447 and Robertet go:

And Robertet's French:Tempore conculcor quantumlibet inclita fama

Me extingunt quamvis tempora sera piam

Quid prodest vixisse diu, cum fortiter evo.

Abdidit in latebris, iam mea tempus edax.

Temporibus fulcor quantumlibet inclita Fama

Ipsa me clauserunt tempora serapiam

Quid prodest vixisse diu confortiter evo,

Abdidit in latebris iam mea Tempus edax.

Time tramples on fame no matter how illustrious

Time slowly extinguishes me, however pious [?]

What is the use of having lived long, with strength [or boldness] long-lasting?

Devouring Time has already removed my refuge [?].

Time burns Fame no matter how illustrious

Time itself encompasses me slow-pious [?]

What is the use of having lived comfortably for a long time?

Devouring time has already removed my refuge [?].

The sentiments are all much the same.Quoy que Fame inclite et honnoree

Apres la Mort soit de longue durée

Clere et luysant, neantmoings tout se passe,

Tout s'oblie par temps et long espace.

Longuement vivre, que t’aura proffite

Quant tu seras es latebres gecte

De ce vieil Temps, qui tout ronge et affine

Et dure après que Fame meurt et fine.

However Fame illustrious and honored

After Death be of long duration

Clear and shiny, nevertheless all passes,

Everything is forgotten by time and long space.

Living long, will it benefit you,

When your refuge is thrown away

By this old Time, which gnaws and refines all

And lasts after Fame dies and ends.

In the last triumph, the quatrain is the same as the others, but leaving out the word "abibunt", which the editor has inserted, I assume from the c. 1447. and not Robertet's "adibunt", which is a misspelling or typo.

Here is the French:Ipsa triumphali prestans regina tropheo.

De veteri palmam, tempora leta gero;

Rex, amor atque pudor, mors, fama et tempus [abibunt] ;

Felices animas regia nostra tenet.

The queen herself, presenting the triumphant trophy,

Of the old palm, slain time bears.

King, love, and pudor [modesty], death, fame, and time will pass away.

Our kingdom holds happy souls.

And for comparison, Robertet:Royne suis, donnant palme et victoire

De vieux triumphe aux triumphans notore

Et temps joieux d’etemelles durees;

Roy, amour, mort, honte, los transitore

Et temps s’en vont, mais pour don meritore

En nostre hostel sont âmes bien eurees.

Queen I am, giving palm and victory

From old triumphs to triumphing knower [?}

And joyful times of eternal duration;

King, love, death, shame, the transitors

And time goes away, but for meritorious gift

In our shelter are very happy souls.

Again, adding the crown, and without Molinet's "eternal duration" that exists when time has "gone away." I am not sure what "j'ay ma mention" refers to - the Virgin's pleas for souls that Christ would otherwise condemn?Je suis séant au hault triumphal throsne;

Du Temps passe porte palme et couronne

Joyeusement comme victorieuse,

Sur les choses creees glorieuse.

Mondaine Amour et Chastete pudicque.

Mort, Fame et Temps, tant soit vieil et anticque:

Tout prandra fin, mais j’ay ma mention

Eterne au ciel en clere vision.

I am seated at the high triumphal throne;

from Time past I bear palm and crown

Joyfully as victorious,

Over glorious created things.

Worldly Love and Pudic Chastity.

Death, Fame and Time, however old and ancient:

Everything will end, but I have my mansion

Eternal in heaven in clear vision.

Added later: I see from Douglas's critical edition (p. 74) that a later copy (BnF Fr. 1717) substitutes "mansion" for "mention." In that case "mention" is probably an archaic version of "mansion," or a scribal error, and the "my" refers simply to the personified Eternity and not the Virgin. The sense of "mansion" corresponds to Molinet's "hostel."

I think my efforts this time are better than before, but there were still things that didn't quite make sense, and I'm sure there's room for improvement.

Last edited by mikeh on 21 Nov 2023, 22:09, edited 2 times in total.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

160Just a couple of quick points because I once again have absolutely no time (I shouldn't even be doing this but it was an irresistible opportunity to procrastinate):

suppeditare is actually another bit of non-classical Latin in the quatrains. The first meaning given for this verb in The Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources (DMLBS) is "to trample underfoot": https://logeion.uchicago.edu/suppeditare

(Logeion appears to be the best Latin dictionary website by far, but do note that all the verbs in the DMLBS are listed under their infinitive forms, not the first person singular active as in most Latin dictionaries. So you always need to search for both.)

As you will no doubt realize, this meaning fits perfectly with the Latin author's general obsession with emphasizing the calcatio aspect of the images whenever possible, an obsession that Robertet and the other French authors evidently (and not surprisingly) did not share, as they dropped several of the references to it in their versions.

However, it does very much appear that Robertet was the one who added this word: the version of this quatrain in ms. 5065 (f. 130r) has "ecce heu". Both of you seem to have forgotten that I cited ms. 5065 and its second volume ms. 12424 as containing versions of the quatrains that are closer to the Modena manuscript than Robertet's version is. I also pointed out that ms. 5065 contains the vincits too. So it really does look like its compiler was working directly from the same Italian manuscript that Robertet was using, and as far as the quatrains are concerned at least, he stuck closer to that text than Robertet did (although Robertet was probably more faithful in the wording of the vincits).

This means that the Italian manuscript Robertet was using almost certainly had "ecce heu" here, and it was Robertet who added "sed", to correct the meter.

(The meter is the elegiac couplet.)

suppeditare is actually another bit of non-classical Latin in the quatrains. The first meaning given for this verb in The Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources (DMLBS) is "to trample underfoot": https://logeion.uchicago.edu/suppeditare

(Logeion appears to be the best Latin dictionary website by far, but do note that all the verbs in the DMLBS are listed under their infinitive forms, not the first person singular active as in most Latin dictionaries. So you always need to search for both.)

As you will no doubt realize, this meaning fits perfectly with the Latin author's general obsession with emphasizing the calcatio aspect of the images whenever possible, an obsession that Robertet and the other French authors evidently (and not surprisingly) did not share, as they dropped several of the references to it in their versions.

I hadn't actually noticed that (or if I had, I had forgotten). Thanks for pointing it out, Ross. At some stage, I should go through the Modena quatrains and check the scansion, to see if there are any other indications of copying errors: the "esse" definitely looks like a mistake because there is an error in the meter there, which is fixed by Robertet's addition of "sed".Ross Caldwell wrote: 27 Oct 2023, 15:24 It is interesting that the only difference between U.07.24 and Robertet in the Death triumph is in the fourth line, where the former reads "Esse. Heu" and the latter reads "Ecce sed heu."

However, it does very much appear that Robertet was the one who added this word: the version of this quatrain in ms. 5065 (f. 130r) has "ecce heu". Both of you seem to have forgotten that I cited ms. 5065 and its second volume ms. 12424 as containing versions of the quatrains that are closer to the Modena manuscript than Robertet's version is. I also pointed out that ms. 5065 contains the vincits too. So it really does look like its compiler was working directly from the same Italian manuscript that Robertet was using, and as far as the quatrains are concerned at least, he stuck closer to that text than Robertet did (although Robertet was probably more faithful in the wording of the vincits).

This means that the Italian manuscript Robertet was using almost certainly had "ecce heu" here, and it was Robertet who added "sed", to correct the meter.

(The meter is the elegiac couplet.)