Here is the best discussion I have found so far on the winged mastiff.

Important point: it is first attested in 1335 on a seal of Mastino II. Perhaps the image of the seal mentioned below can be found.

The note 25 to this statement is “Gerola 1930, p. 135-136 and Plessi 1988, p. 71-76: Mastino uses this new seal both in documents signed together with his brother Alberto, on the co-titled paper of the lordship, and in those issued under his own name.”

The bibliography is: Gerola 1930 = G. Gerola, Sigilli scaligeri, in Studi medievali, 1, 1930, p. 130-141 and Plessi 1988 = G. Plessi, Sigilli scaligeri, in Varanini 1988, p. 71-76.

See the paper at the link below for all of the notes and bibliography.

Matteo Ferrari, “Il cimiero: espressione dell’identità, insegna dinastica, simbolo di rango (Lombardia e Veneto, XIV secolo”

"The crest: expression of identity, dynastic emblem, symbol of rank (Lombardy and Veneto, 14th century)"

https://journals.openedition.org/mefrm/ ... g=it#ftn25

La propensione per l’araldica delle famiglie signorili dell’Italia settentrionale, così come di quelle che ne frequentavano la corte, è cosa nota. Strumento di rappresentazione personale e del lignaggio, anche con finalità che potremmo definire politiche, lo stemma del signore permeava il territorio da questi governato. Raffigurato sugli edifici privati come su quelli pubblici, sui sigilli come sulle monete, lo stemma era spesso associato ad altri elementi para-araldici ed emblematici, che ne affinavano il significato. Tra questi, i monogrammi composti dalle iniziali del portatore dell’insegna e, per l’appunto, i cimieri personalizzavano l’arme familiare, per sua natura collettiva, e permettevano di distinguere l’individuo all’interno del suo clan15. Lungi dal costituire un mero espediente d’identificazione, il cimiero era però un segno dalla natura polisemica, che ben si prestava a supportare la politica d’immagine signorile.

Negli anni Venti-Trenta del Trecento, i signori di Verona furono così tra i primi ad accogliere il cimiero all’interno della panoplia araldica familiare e a metterlo a contribuzione nell’ambito di quella politica d’immagine da loro avviata a breve intervallo dalla presa di potere, avvenuta negli anni Sessanta del Duecento con Mastino della Scala († 1277)16. Se il controllo della suprema magistratura di Popolo garantiva alla famiglia la trasmissione del governo, questa rimaneva però formalmente subordinata alla volontà dell’assemblea cittadina cui spettava l’effettivo conferimento dei poteri17. Al pari di altri regimi signorili contemporanei, gli Scaligeri accompagnarono allora la ricerca di fonti diverse di legittimazione, esterne al contesto locale, alla messa in opera di una campagna d’immagine diretta a esibire tanto il prestigio della famiglia, quanto a documentare la continuità della trasmissione del potere all’interno del lignaggio.

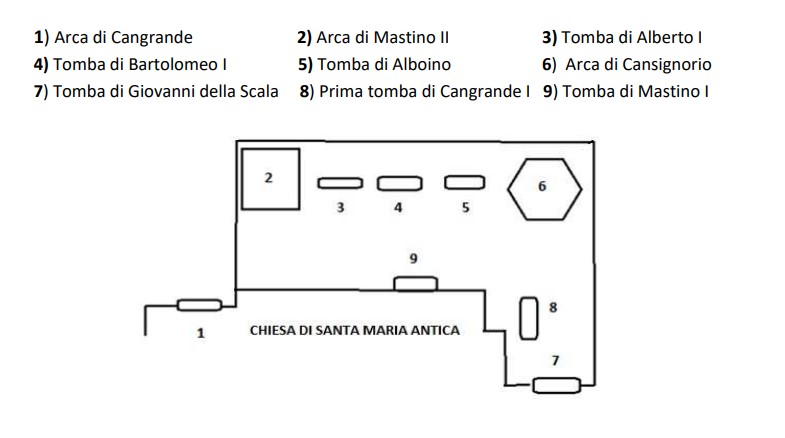

La costruzione del sepolcreto familiare attorno alla chiesa di Santa Maria Antiqua, situata nei pressi delle residenze scaligere, rispondeva, con le sue componenti emblematiche, a quest’esigenza18. Se la celebrazione del defunto era stata inizialmente affidata alla collocazione e alla tipologia prestigiosa dell’arca, ispirata al modello dei sarcofagi porfiretici antichi, col passare delle generazioni le componenti figurative, e tra di esse quelle araldiche, assunsero un’importanza crescente. Utile per visualizzare i legami dinastico-familiari e gli orientamenti politici del lignaggio, l’araldica fece la sua comparsa nella tomba attribuita ad Alberto I († 1301) e in quella di Bartolomeo († 1304): la scala dell’insegna familiare forniva qui l’appoggio a un’aquila coronata, segno d’appartenenza ghibellina19. Nell’arca di Alboino († 1311) e nella prima di Cangrande I († 1329), lo stemma della Scala fu invece accostato a quello imperiale, in riferimento al vicariato che entrambi avevano ottenuto e che aveva loro assicurato quella fonte di legittimazione esterna che dava prestigio e autonomia al loro potere20.

Durante la signoria di Mastino II, il progressivo indebolimento della potenza militare e territoriale della signoria – dal 1341 ridotta alle sole città di Verona e Vicenza e minacciata dall’ascesa della vicina Padova carrarese – accrebbe l’esigenza di una politica d’immagine forte, centrata su simboli di sicura presa. Attorno alla metà degli anni Trenta, e forse dopo la perdita di Padova nel 1337, Mastino diede così nuovo impulso alla politica d’immagine familiare. L’assetto del sepolcreto scaligero fu dunque mutato per dare una più maestosa sepoltura al suo predecessore Cangrande, la cui gloriosa memoria poteva servire da puntello per l’indebolita dinastia. Abbandonando la sobrietà delle prime arche, il nuovo mausoleo, posto sopra l’ingresso della chiesa e coronato dal monumento equestre del defunto, assumeva una veste pienamente monumentale. Le scene scolpite sulla cassa commemoravano le conquiste territoriali dello Scaligero, rammentando il ruolo di potenza regionale che i Della Scala avevano assicurato a Verona e, implicitamente, rivendicavano il possesso dei territori recentemente perduti.

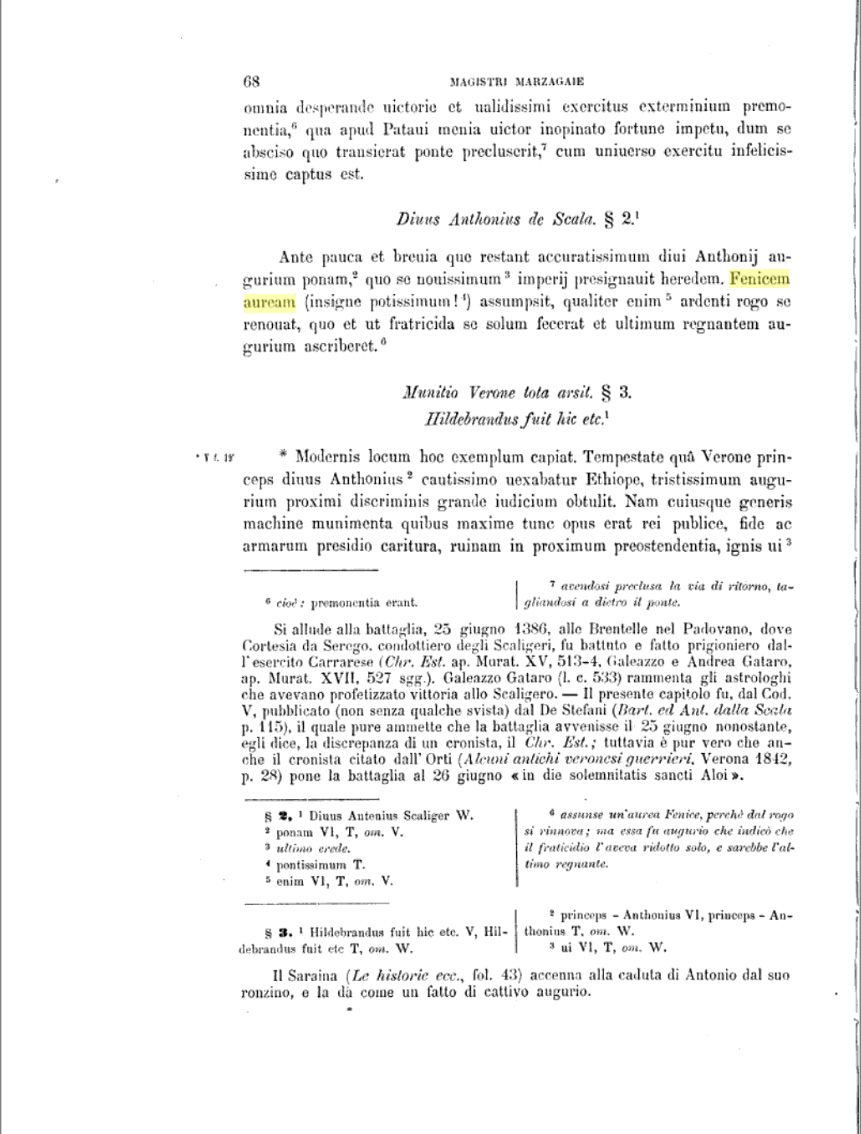

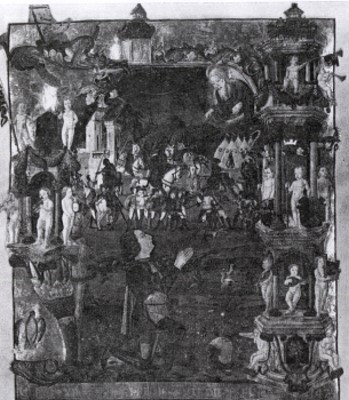

Il mutare della sepoltura fu accompagnato dall’ampliamento della panoplia araldica. Lo constatiamo innanzitutto nella comparsa del celebre cane, che fu tanto impiegato in funzione di tenente dello stemma familiare (coronato in riferimento alla dignità signorile), quanto integrato all’interno dello scudo, a sostegno della scala. Veniva così trasposto in ambito monumentale un elemento emblematico che Cangrande aveva già impiegato nel tipario sigillare, anche qui con funzione di reggente dello scudetto scaligero21. Figura parlante, allusiva al nome del signore, il cane si era del resto rapidamente affermato nell’immaginario della signoria, al punto che già durante il principato di Cangrande i cronisti apostrofavano i sovrani veronesi con l’appellativo di canes veronenses22. Assolutamente inedito era invece il cimiero col mastino alato posto ad ornamento dell’elmo del signore nella scultura equestre e nel rilievo dedicato alla battaglia del 1314 per la difesa di Vicenza (fig. 3-4): collarinato, coronato e dotato di grandi ali come d’uso nei cimieri dell’Europa settentrionale23. In effetti, né Cangrande, né tantomeno i suoi predecessori sembrano aver mai impiegato tale elemento araldico. Se ignoriamo quali sembianze avesse «‘l cimier sovrano» citato tra le insegne che accompagnarono il feretro di Cangrande durante il suo funerale24 (1329), pare comunque significativo che il mastino alato non sia mai documentato prima del 1335, quando apparve sul sigillo che Mastino II appose in calce a un atto25.

Secondo Ettore Napione l’invenzione di questo cimiero sarebbe connessa all’operazione di costruzione di un’ascendenza mitica e illustre che gli Scaligeri misero in atto fin dagli esordi della signoria, appoggiandosi sul passato longobardo e regale di Verona. La strategia si basava sulle scelte onomastiche, come rivelano la resurrezione dell’inusuale nome di Alboino, primo re longobardo morto e sepolto nella città veneta, e, forse, la sistematica adozione di nomi dall’etimo canino (Cangrande, Canfrancesco detto Cansignorio, Mastino). Collante dinastico tributario del soprannome di Mastino affibbiato al ‘fondatore’ della dinastia, Leonardino della Scala, l’impiego di questi nomi avrebbe permesso alla famiglia veronese, secondo Napione, di evocare il ricordo dei ferocissimi guerrieri cinocefali, leggendarie figure delle saghe germaniche, attribuendosene le virtù di combattenti irriducibili26. L’ipotesi è certo affascinante, ma ci chiediamo se il mastino alato non avesse piuttosto svolto, ai suoi esordi, la funzione di una semplice insegna parlante. Questa permetteva al suo portatore tanto di segnalarsi all’interno del clan familiare, quanto di attribuirsi quelle doti di ferocia guerriera che, già insite nel suo nome di battesimo, erano ora esibite in modo ben più icastico dalla temibile figura canina che lo rappresentava nei tornei, in battaglia e nelle rappresentazioni della sua signoria. Non si dimentichi del resto che gli Scaligeri non furono i soli signori dell’Italia settentrionale a riesumare il passato longobardo a fini politici: lo fecero anche i Visconti, a partire dal secondo Trecento, ma tale operazione non ebbe alcuna incidenza sul piano onomastico o araldico27

Per quale ragione però Mastino II, sulla metà degli anni Trenta, decise prima d’impiegare il mastino alato come cimiero personale, poi d’integrarlo nella panoplia araldica famigliare come un’insegna della signoria, attribuendolo a posteriori al suo predecessore Cangrande? Crediamo che la risposta vada cercata nel quadro politico dell’epoca, segnato dal conflitto che opponeva i signori veronesi, ghibellini, al fronte guelfo: un conflitto nel quale persino gli stemmi erano oggetto di attacchi verbali fornendo materia per la denigrazione dell’avversario. Raccogliendo una tradizione diffusa, Giovanni Villani prese spunto dallo stemma parlante degli Scaligeri per insinuarne l’umile origine da un produttore di scale, che avrebbe dato alla sua stirpe il nome e l’insegna. Parvenus con arie di principi, alla ricerca di fonti di legittimazione per la loro signoria, gli Scaligeri non furono insensibili alla polemica, come evidenzia l’imponente macchina di propaganda da loro creata e continuamente alimentata28. Il cimiero col mastino alato consentiva allora tanto d’integrare l’araldica famigliare con una figura fiera e temibile, quanto di nobilitarla, grazie all’attributo della corona che, come Ettore Napione ha giustamente rilevato, andrà probabilmente letto in relazione alle ambizioni regali di Mastino29. La stretta connessione con la tradizione onomastica familiare, poi, offriva la garanzia della riconoscibilità del segno, facilmente riconducibile alla famiglia veronese. Attribuendo la propria insegna all’illustre predecessore, come in una sorta di concessione araldica a parti rovesciate, Mastino si presentava come suo diretto e legittimo erede, unico in grado di rinverdirne i fasti30.

La funzione ‘politica’ del cimiero sembra del resto dimostrata dalla sua immediata trasformazione in «emblema stabile della signoria»31. Questo consentiva di mettere visivamente in risalto il legame genealogico tra il signore e i suoi predecessori e di affermare, di conseguenza, la legittimità del trapasso dei poteri all’interno del lignaggio. Ornati delle insegne familiari e, soprattutto, dei loro cimieri, i monumenti equestri che si fronteggiavano nel sepolcreto di Santa Maria Antiqua diffondevano l’immagine di una signoria coesa. Oltre che nella tomba di Cangrande, il cimiero col mastino compare infatti in quella di Mastino II, completata all’indomani della sua morte nel 1351 per mano della stessa maestranza che aveva realizzato il sepolcro del suo predecessore32 (fig. 5): lo vediamo sull’elmo che copre la testa della statua equestre, sulla testiera del cavallo e sui timpani delle edicole sottostanti. Ed era senz’altro dotata di cimiero anche la figura equestre di Cansignorio, posta a coronamento della monumentale sepoltura realizzata e sottoscritta da Bonino da Campione nel 1375, come lo sono le edicole che formano il secondo ordine del sepolcro33.

Lungo il filo delle generazioni, il cimiero scaligero fu dunque riprodotto, da solo o associato allo stemma familiare, nei luoghi di rappresentanza della signoria. Alla ricerca di un difficile equilibrio tra l’esigenza di manifestare l’appartenenza al clan familiare e la volontà d’affermazione individuale, il cimiero col mastino presenta talvolta piccole varianti atte a singolarizzarlo. Forse privo di corona è quello dipinto sulla volta di un’aula della cosiddetta Torre del Capitano, residenza scaligera compresa nel complesso su Piazza dei Signori e rinnovata durante gli anni di Cansignorio34 (fig. 6). Privo di corona ed anche delle ali, ma con lunghe orecchie d’oro e ricoperto di piccole scale, è quello che accompagna il presunto ritratto di Cangrande II (1351-59) nella Madonna del rosario di Lorenzo Veneziano in Sant’Anastasia35.

Ma è sui sigilli e sulle monete, notoriamente veicolo primario per la diffusione dell’immagine del potere, che i successori di Mastino II fecero ampio uso del mastino alato. Lo mostrano il sigillo, per l’appunto, di Cangrande II, da questi impiegato anche negli atti siglati congiuntamente con i fratelli Cansignorio e Paolo Alboino36, e quelli di Bartolomeo e di Antonio. Durante la loro fragile signoria, questi ultimi – prima congiuntamente (1375-81), poi dopo la morte di Bartolomeo il solo Antonio (1381-87) – coniarono anche monete col cimiero del mastino alato37. Antonio, amante delle preziosità e del lusso, lo fece raffigurare pure in prodotti destinati a una circolazione più limitata o a un’esibizione esclusiva nell’ambito della corte. La carta d’apertura del Commento alle Lettere degli apostoli e all’Apocalisse (Città del Vaticano, BAV, Cod. Pal. Lat. 112) fu così ornata con lo stemma del signore (uno scudo con la scala compreso fra le lettere A e N, iniziali di Antonio), timbrato da un elmo sormontato dal cimiero con il mastino alato, collarinato e coronato: la rappresentazione della panoplia scaligera al gran completo garantiva l’identificazione del proprietario del codice, in base a una pratica che nella seconda metà del Trecento era ormai diventata del tutto comune38. Nel caso dei figli di Cansignorio, poi, l’assenza di un qualunque rapporto con l’onomastica del portatore dell’insegna conferma l’avvenuta trasformazione del mastino alato in insegna della signoria e il suo impiego, negli anni del rapido declino dell’egemonia scaligera come strenua affermazione d’autorità. E d’altra parte è senz’altro in quest’accezione che tale cimiero fu recuperato da Brunoro durante l’effimera rinascita della signoria degli Scaligeri nel 1404(39).

The propensity for heraldry among the noble families of northern Italy, as well as those who frequented their courts, is well-known. As a tool for personal and lineage representation, with political implications, the lord's coat of arms permeated the territory under their rule. Displayed on both private and public buildings, seals, and coins, the coat of arms was often associated with other heraldic and emblematic elements that refined its meaning. Among these, the monograms composed of the bearer's initials and, notably, the crests personalized the family's armor, which by its nature was collective, and allowed for the individual's distinction within their clan. Far from being a mere identification device, the crest was a multi-layered symbol that lent itself well to supporting the noble's image politics.

In the 1320s and 1330s, the lords of Verona were among the first to adopt the crest within their family heraldic arsenal and to employ it as part of their image politics shortly after coming to power in the 1260s with Mastino della Scala († 1277). While the control of the supreme magistracy of the People ensured the family's transmission of power, it remained formally subordinate to the will of the city assembly, which held the actual conferral of powers. Similar to other contemporary noble regimes, the Scaligeri sought alternative sources of legitimacy outside the local context and embarked on an image campaign to showcase both the family's prestige and the continuity of power transmission within the lineage.

The construction of the family burial site around the Church of Santa Maria Antiqua, located near the Scaliger residences, responded, with its emblematic components, to this need. While initially the commemoration of the deceased was entrusted to the placement and prestigious typology of the ark, inspired by the model of ancient porphyry sarcophagi, over the generations the figurative components, including the heraldic ones, gained increasing importance. Useful for visualizing the dynastic-family ties and the political orientations of the lineage, heraldry made its appearance in the tomb attributed to Alberto I († 1301) and in that of Bartolomeo († 1304): the scale of the family insignia provided support here to a crowned eagle, a sign of Ghibelline belonging. In the tomb of Alboino († 1311) and in the first one of Cangrande I († 1329), the Scala coat of arms was instead juxtaposed with the imperial one, referring to the vicariate that both had obtained and which had ensured them a source of external legitimacy that gave prestige and autonomy to their power.

During the lordship of Mastino II, the progressive weakening of the military and territorial power of the lordship - reduced since 1341 to only the cities of Verona and Vicenza and threatened by the rise of neighboring Carrara-led Padua - increased the need for a strong image policy centered on symbols of certain impact. Around the mid-1330s, perhaps after the loss of Padua in 1337, Mastino thus gave new impetus to the family's image policy. The layout of the Scaliger burial site was therefore changed to provide a more majestic burial for his predecessor Cangrande, whose glorious memory could serve as a pillar for the weakened dynasty. Abandoning the sobriety of the early arks, the new mausoleum, placed above the entrance of the church and crowned by the equestrian monument of the deceased, assumed a fully monumental appearance. The sculpted scenes on the casket commemorated the territorial conquests of the Scaliger family, recalling the role of regional power that the Della Scala had secured for Verona and implicitly claiming possession of the recently lost territories.

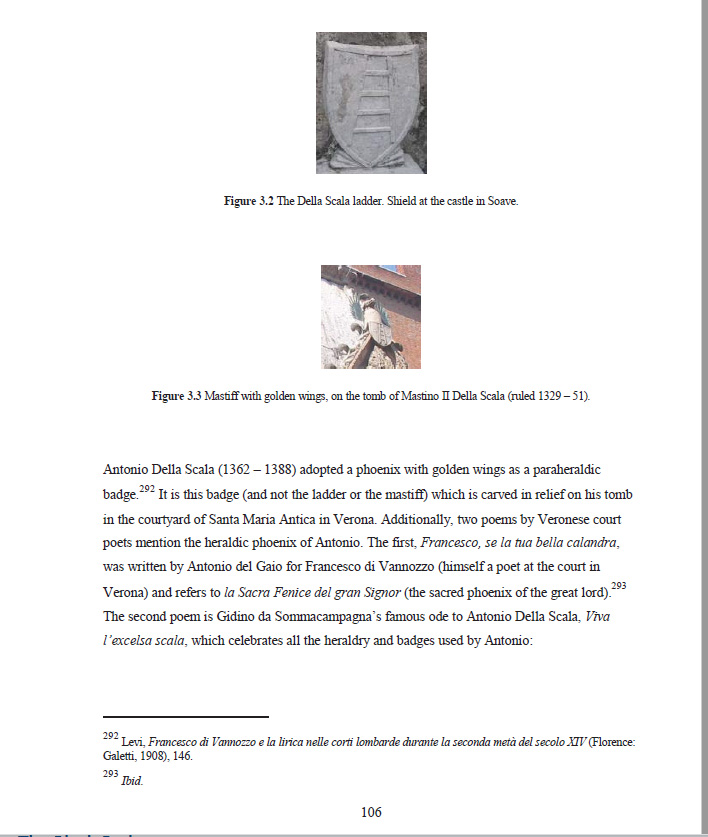

The changing of the burial was accompanied by the expansion of the heraldic display. We observe this first and foremost in the emergence of the famous dog, which was employed both as a supporter of the family coat of arms (crowned to indicate noble dignity) and integrated within the shield, supporting the ladder. Thus, an emblematic element that Cangrande had already used in his seal designs was transposed into the realm of monuments, serving as the regent of the Scaliger shield. The dog, a speaking figure alluding to the lord's name, had quickly established itself in the imagery of the ruling class, to the extent that during the principality of Cangrande, chroniclers referred to the Veronese rulers as "canes veronenses."

However, the crested helmet with a winged mastiff, featured as an ornament on the lord's helmet in the equestrian sculpture and the relief dedicated to the defense of Vicenza in the 1314 battle (fig. 3-4), was completely unprecedented. Collared, crowned, and equipped with large wings, it followed the customary style of crests in Northern Europe. In fact, neither Cangrande nor his predecessors seem to have ever used such a heraldic element. While we are unaware of the exact appearance of the "sovereign crest" mentioned among the insignia that accompanied Cangrande's coffin during his funeral (1329),

it is nonetheless significant that the winged mastiff is not documented prior to 1335, when it appeared on the seal that Mastino II affixed to a document.

According to Ettore Napione, the invention of this crest would be connected to the operation of constructing a mythical and illustrious lineage that the Scaligeri implemented from the very beginning of their rule, relying on the Lombard and royal past of Verona. The strategy was based on onomastic choices, as revealed by the resurrection of the unusual name Alboino, the first Lombard king who died and was buried in the Venetian city, and perhaps the systematic adoption of names derived from the canine etymology (Cangrande, Canfrancesco known as Cansignorio, Mastino). As a dynastic bond tributary to the nickname "Mastino" attached to the "founder" of the dynasty, Leonardino della Scala, the use of these names would have allowed the Veronese family, according to Napione, to evoke the memory of the ferocious cynocephalous warriors, legendary figures from Germanic sagas, attributing to themselves the virtues of unyielding fighters. The hypothesis is certainly fascinating, but we wonder if the winged mastiff initially served as a simple speaking emblem. This allowed its bearer to both distinguish themselves within the family clan and attribute those qualities of warrior ferocity that were already inherent in their given name, now exhibited in a more iconic manner by the formidable canine figure representing them in tournaments, battles, and representations of their rule. It should not be forgotten that the Scaligeri were not the only lords of northern Italy to resurrect the Lombard past for political purposes: the Visconti also did so, starting from the 14th century, but this operation had no impact on the onomastic or heraldic level.

For what reason, however, did Mastino II decide, in the mid-1330s, to first use the winged mastiff as his personal crest and then integrate it into the family heraldic panoply as a sign of lordship, attributing it retrospectively to his predecessor Cangrande? We believe that the answer must be sought in the political framework of the time, marked by the conflict between the Ghibelline lords of Verona and the Guelph front: a conflict in which even coats of arms were subjected to verbal attacks, providing material for the denigration of the adversary. Drawing on a widespread tradition, Giovanni Villani took inspiration from the speaking coat of arms of the Scaligeri family to insinuate its humble origin from a ladder manufacturer, who would have given his lineage its name and emblem. As parvenus with airs of princes, in search of sources of legitimacy for their lordship, the Scaligeri were not immune to the controversy, as evidenced by the imposing propaganda machine they created and continuously fueled. The crest with the winged mastiff allowed them both to integrate the family heraldry with a proud and fearsome figure and to ennoble it, thanks to the attribute of the crown which, as Ettore Napione rightly pointed out, is probably to be interpreted in relation to Mastino's royal ambitions. The close connection with the family's onomastic tradition also offered the guarantee of the sign's recognizability, easily attributable to the Veronese family. By attributing his own emblem to the illustrious predecessor, as if in a kind of reversed heraldic concession, Mastino presented himself as his direct and legitimate heir, the only one capable of reviving its former splendor.

The 'political' function of the crest, moreover, seems to be demonstrated by its immediate transformation into the "stable emblem of lordship." This visually emphasized the genealogical connection between the lord and his predecessors and consequently asserted the legitimacy of the transfer of power within the lineage. Adorned with family insignias and, above all, their crests, the equestrian monuments facing each other in the burial ground of Santa Maria Antiqua spread the image of a cohesive lordship. In addition to Cangrande's tomb, the crest with the mastiff also appears in Mastino II's tomb, completed after his death in 1351 by the same craftsmanship that had created his predecessor's tomb: we see it on the helmet covering the head of the equestrian statue, on the horse's headgear, and on the tympana of the underlying shrines. Undoubtedly, the equestrian figure of Cansignorio, placed as the crowning piece of the monumental burial realized and subscribed by Bonino da Campione in 1375, was also equipped with a crest, as are the shrines that form the second order of the tomb.

Along the thread of generations, the Scaliger crest was thus reproduced, either alone or associated with the family coat of arms, in the representative places of the lordship. In search of a difficult balance between the need to manifest belonging to the family clan and the desire for individual affirmation, the crest with the mastiff sometimes presents small variations aimed at individualizing it. Perhaps without a crown is the one painted on the vault of a hall in the so-called Tower of the Captain, a Scaliger residence included in the complex on Piazza dei Signori and renovated during the years of Cansignorio34 (fig. 6). Without a crown and also without wings, but with long golden ears and covered in small scales, is the one accompanying the presumed portrait of Cangrande II (1351-59) in the Madonna del Rosario by Lorenzo Veneziano in Sant'Anastasia35.

But it is on seals and coins, notoriously the primary vehicle for the dissemination of power's image, that the successors of Mastino II made extensive use of the winged mastiff. This is demonstrated by the seal, precisely, of Cangrande II, which he also used in jointly signed deeds with his brothers Cansignorio and Paolo Alboino36, and those of Bartolomeo and Antonio. During their fragile lordship, the latter – first jointly (1375-81), then after Bartolomeo's death only Antonio (1381-87) – also minted coins with the crest of the winged mastiff37. Antonio, a lover of precious items and luxury, had it depicted in products intended for more limited circulation or exclusive exhibition within the court. The opening page of the Commentary on the Letters of the Apostles and the Apocalypse (Vatican City, BAV, Cod. Pal. Lat. 112) was adorned with the lord's coat of arms (a shield with the ladder enclosed between the letters A and N, initials of Antonio), crowned and crested by a helm with the winged mastiff: the representation of the complete Scaliger panoply ensured the identification of the owner of the codex, based on a practice that had become completely common in the second half of the 14th century38. In the case of Cansignorio's sons, then, the absence of any connection with the onomastics of the bearer of the insignia confirms the transformation of the winged mastiff into a lordship emblem and its use, in the years of the rapid decline of Scaliger hegemony, as a strong assertion of authority. On the other hand, it is undoubtedly in this sense that such a crest was recovered by Brunoro during the ephemeral revival of the Scaliger lordship in 140439.