In discussing the good/evil "signs" held by the kings and marschalli in another thread I referred to this deck and asked if anyone knew of studies of it - I can't find anything but the most trivial of descriptions, so in part this is a call for links to any studies anyone may know of. Not even the dating seems conclusive but this is clearly one of the oldest decks to survive. I've seen 1390 banded about on various Spanish webpages, but the museum webpage itself gives 1400-1420, while their curated exhibition shows 1390:

What follows is a reconstruction of that deck that shockingly points to a 60 card - the magical number of an ideal deck in JvR.

WOPC offers this: https://www.wopc.co.uk/spain/morsica#:~ ... 0expensive.

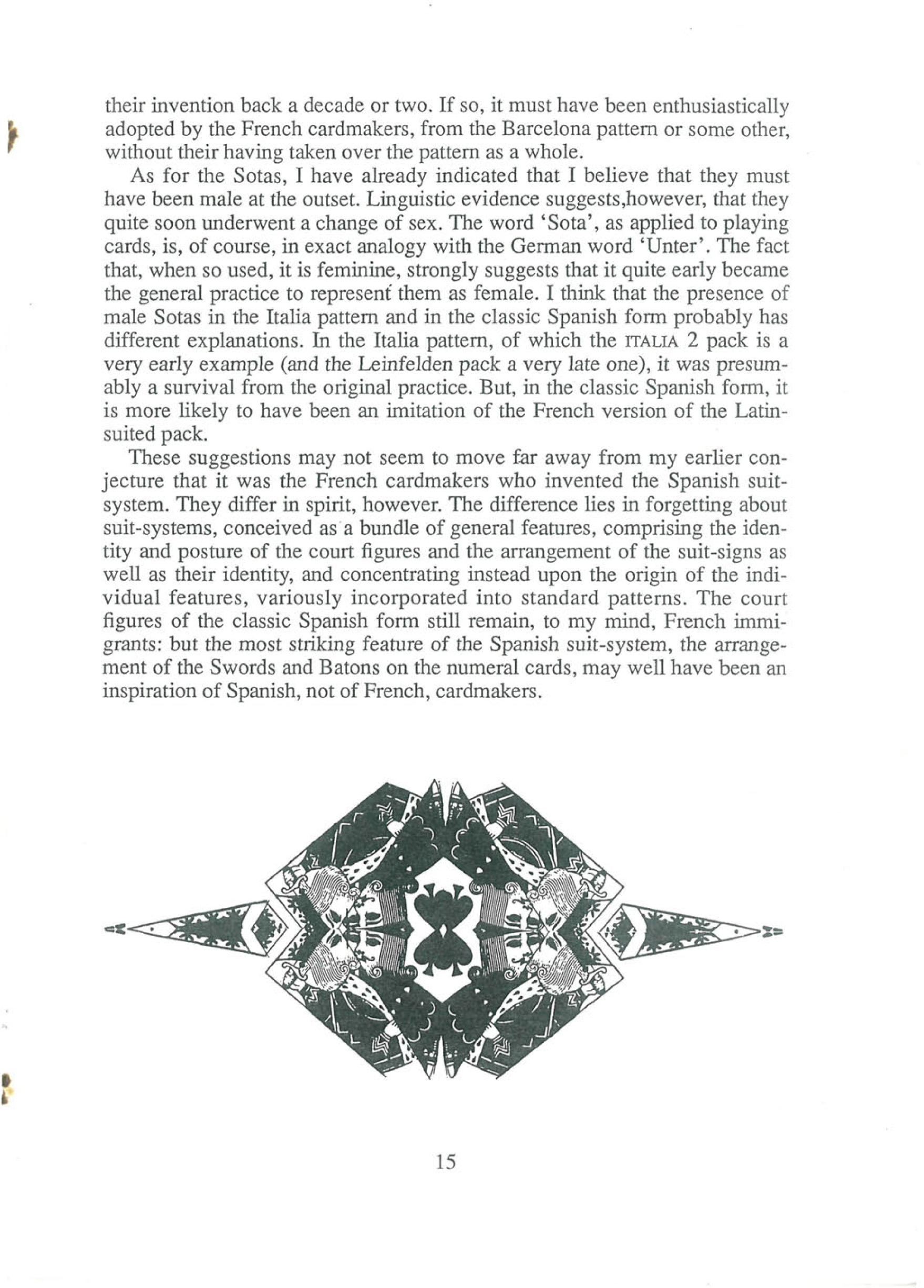

Actually the Fournier link just goes to a general link; the deck in question is here: https://apps.euskadi.eus/emsime/catalog ... ninv-44519Above [image not included, but just some of the cards]: cards from a primitive Latin suited pack, possibly of Swiss or German origin for export to Spain, dated by paper analysis as “early XV century”, which makes this one of the earliest known surviving packs of playing cards. There are Moorish influences in some of the cards: see the double-panelled Saracenic shield on the cavalier of swords (bottom row).

The cards show lingering evidence of a suit system derived from early Arabic cards, which in turn became popular throughout Europe from the 15th century. They have been printed from wood blocks and coloured by a technique known as 'a la morisca' which involved using the fingers dipped into the pigment. This is different from other early packs of cards which were hand-painted or illuminated and therefore more expensive. As their popularity spread, new methods of production were discovered to produce packs of playing cards more cheaply. Cards in the Museo "Fournier" de Naipes de Alava.

Museo "Fournier" de Naipes de Alava Arabako "Fournier" Karta Museoa

Images on this page of cards in the Museo "Fournier" de Naipes de Alava (Diputación Foral de Alava, Cuchillería 54, 01001 Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain) are taken from Agudo Ruiz (2000) and Suarez Alba (1991). Used with permission.

The museum webpage gives a fairly large bibliography, but most of these are 1 or 2 page entries that are seemingly cursory descriptions without any broader insights offered. Ross, any chance you have access to the first Dummett article?

From Denning there is a reference to the earliest Moorish design cards in Barcelona dating to 1414 (Denning, Trevor. The playing-cards of Spain: a guide for historians and collectors. United Kingdom: Cygnus Arts, 1996: 20).BRAUN, Franz. Consolidation of Playing Cards Since 1850. Colonia, Autoedición, 1970-1982. [487]. Nº 1413

PALAU I SALIENT, Doménec. Restauración de 42 naipes del s. XV del Museo Fournier de Vitoria, III Congreso de Restauración de Bienes Culturales. Instituto de Conservación y Restauración de Obras de Arte. Comité Español del ICOM. Valladolid.. 1980. 179-182.

ALFARO FOURNIER, Félix. Los Naipes. Museo Fournier. Vitoria, Heraclio Fournier S.A., 1982. [322], p. 113. Ilustración en p. 110

DUMMETT, Michael. The Earliest Spanish Playing Cards, The Playing-Card. Journal of the International Playing-Card Society, Vol. 18, nº 1. August 1989, pp. 6 - 15

ALFARO FOURNIER, Félix; LLANO GOROSTIZA, Manuel. Vitoria-Gasteiz ciudad del naipe. 75 Aniversario del Museo Fournier. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Caja Vital Kutxa, 1991. [332], p. 20, il. p. 4

DUMMETT, Michael. A Survey of ”Archaic” Italian Cards. A Correction, The Playing-Card. Journal of the International Playing-Card Society, Vol. 19, nº 4. may 1991, pp. 128-131, Addendum

SUAREZ ALBA, Alberto. A Vitoria Barajas. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Diputación Foral de Álava, 1991, il. col. p. 54

DENNING, Trevor. The playing-cards of Spain. A guide for historians and collectors. Londres, 1996. [226].

HOFFMANN, Detlef. Schweizer Spielkarten 1. Die Anfänge im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Schaffhausen, Museum zu Allerheiligen Schaffhausen; Cartophilia Helvetica, 1998. [138], pp. 81 y 82

AGUDO RUIZ, Juan de Dios. Los naipes en España. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Diputación Foral de Álava, 2000, il. col. p. 31

Barajas de colección. Un recorrido por la historia del naipe. Madrid, Ediciones del Prado, 2004. [474], il. col. p. 17

EGUIA LÓPEZ DE SABANDO, José. Naipe de estilo español, ficha del catálogo, Exposición Canciller Ayala. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Diputación Foral de Álava, 2007, p. 296. Ilustraciones en pp. 297-299

GULINELLI, Veber. Delle carte da gioco italiane. Storia e diletto. San Felice sul Panaro, Italia, Edizioni APM, 2011. [488], pp. 15-16, il. col. pp. 17-26

GARRIGUE, Jean-Pierre. La carte à jouer en Catalogne. XIVe & XVe siècles. Saint Estève, Michel Garrigue. Les Presses Littéraires, 2015.

Dummett's 'Archaic' Italian cards article can be read via this Yale viewer here, but not especially helpful: https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2053426

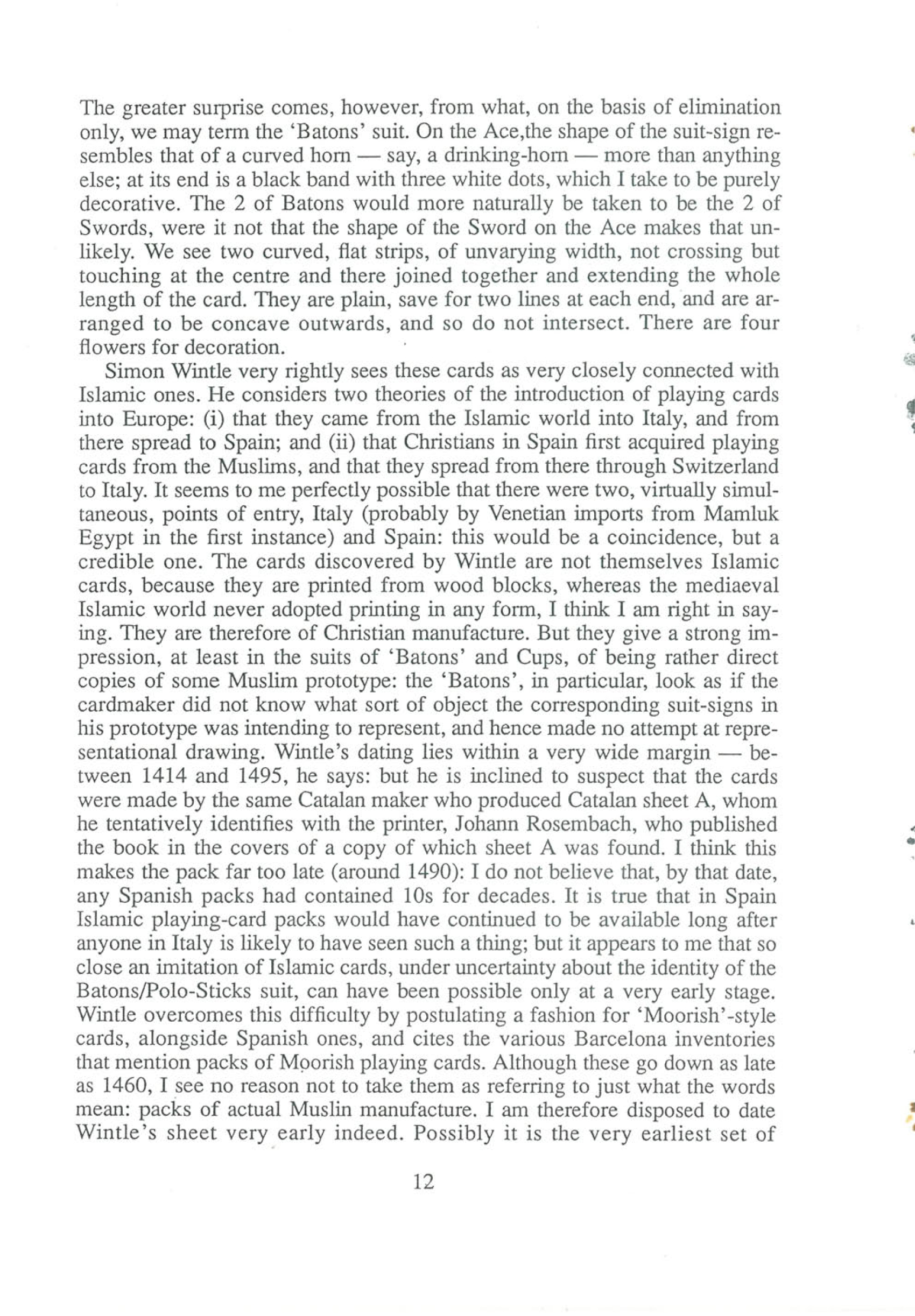

Proceeding ignorant to most of the above, the key descriptive observations of the suits:

1. The court suits and the suit pips do not match in the case of the Sword and Batons, which means the alignment of those pips and court cards is somewhat of a guess

2. Pip suits:

- Acorns (shown with oak leaves in the court cards, but just on a section of rounded twig, looking a bit like the bells in other decks

- Bells (a circle with an "s' opening, also shown on the court cards)

- Swords (what is most odd is that the Ace sword is broken with oak leaves(?) attached to either end, and the Flower/rose suit also at the hilt; implications that those suits can take swords?)

- Batons - clearly Mamluk polo sticks have been retained, testifying to this being an early deck.

- Leaves - this fourth suit is problematic as seemingly a single card from this suit survives in a page (if that upper left blotch is indeed the usual spade-shaped leaf found in Swiss-German decks); it also has enigmatic symbols placed around the figure:

3. Court Suits

Idiosyncrasy besides not matching the pips: some of the court cards hold a sword but the suit sign floating in the empty space above or below them would suggest they don't necessarily belong in the suit of swords, that merely being an attribute of their station as male court cards; e.g. knight.

- Acorns - matches pips, but only the 'Saracen', the stance of the horse is different from all of the others and sign is placed beneath the figure like an Unter Knave; moreover the oak leaves has also been uniquely separated from one another. More on that further below.

- Bells - matches pips.

- Flowers/Roses - goes with Sword pips? The four/five petaled flower (usually called a rose) hovers above all of the surviving court cards of this suit.

- Leaves - just the page noted above. This might have gone with Batons/polo sticks for some reason - wood (staves/sticks/batons) being the basis of this suit of leaves (oak leaf from acorn would also fit, but the focus is on the fruit {nut} of the oak tree in that suit).

Some pre-17th c. Swiss/German deck suits:

c. 1523 S. Beham: Acorns, Leafs, Roses, Pomegranates

c. 1530 Anon. Swiss: Acorns, Flowers, Shields and Bells https://www.wopc.co.uk/switzerland/oldcards

c. 1530 E. Schoen: Roses, Leafs, Grapes, Pomegranates

c. 1535 Schaufelein: Acorns, Leafs, Hearts, and Bells

c. 1541 Flötner: Acorns, Leafs, Hearts and Bells

(source: WOPC for the Swiss deck and Timothy B. Husband, The World in Play: Luxury Cards 1430-1540, 2015: 95-125)

I would suggest the closest subsequent deck would be the c. 1530 anonymous Swiss deck. Acorns, Leafs and Bells are all fairly standard. I would suggest Shields, which naturally parley with Swords, were deemed interchangeable suits by whomever did the subsequent c. 1530 deck. But that just explains the pips; Flowers are present in the Morisca deck, so the shields and flowers are combined into one suit there. The shields do feature a Florentine/French lily design so the connection is already there, thus flowers for the court cards, swords for the pips. Still odd. With the shields/flowers combined, what gets added differently in the Morisca is the Leafs suit (whose pips are arguably the polo sticks).

None of that explains why the pips are different from the court suits in the cases of batons/polo sticks and swords; one might pair the king of flowers with sword pips, but the Saracen knight with an acorn also holds a sword and there is a suit of acorns; I argue the court cards in the suit of Leafs is almost wholly missing and again the only reason to link them with the sticks is that wood/leaves have a natural connection. Clearly suits could have been fluid, especially early on, but there is not a good answer for why this was done for only two suits here. One possibility is that a fairly novel deck was being created and it was using two different decks and combined them in an inconsistent manner. On to the reconstruction...

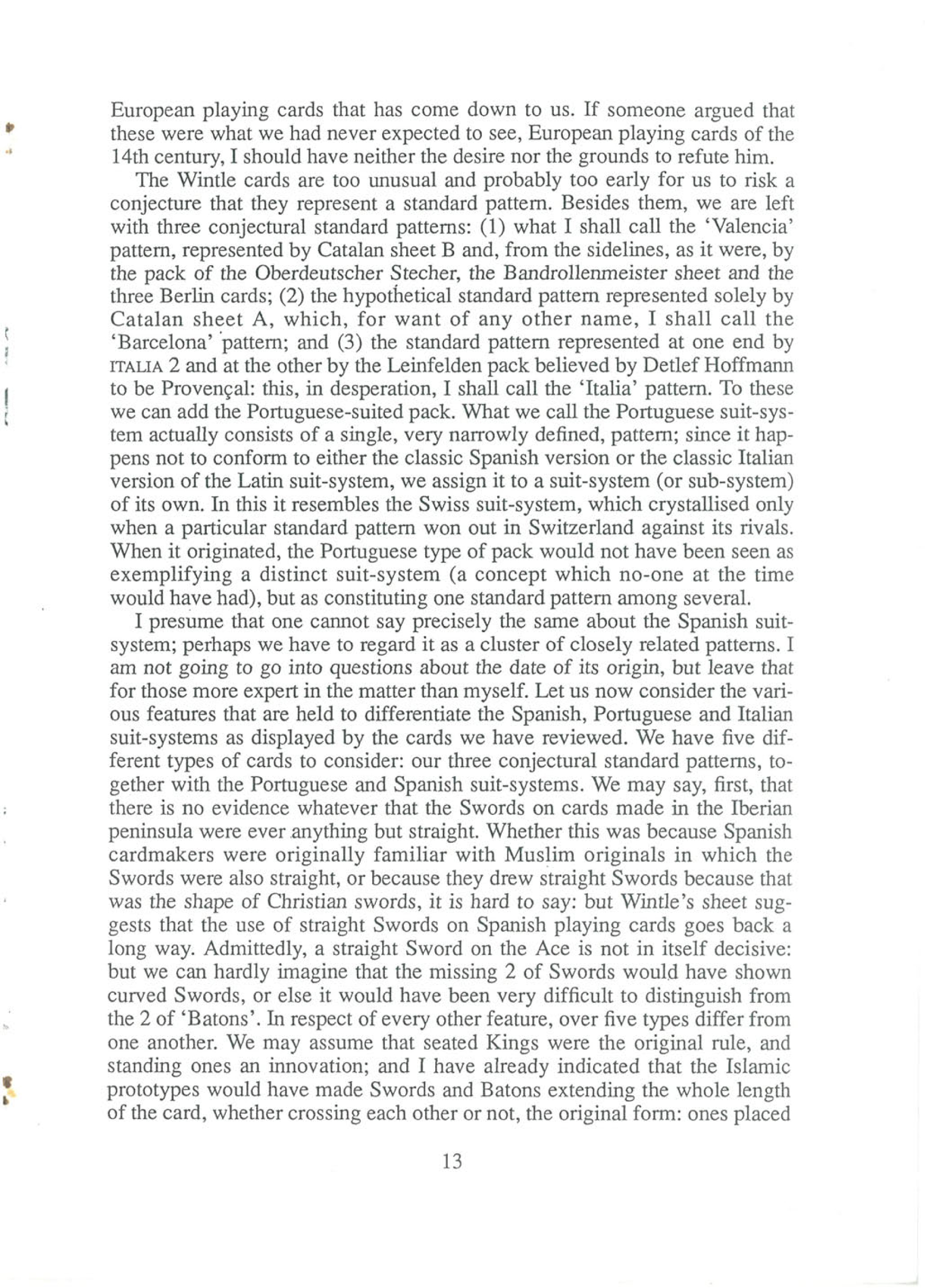

Reconstruction of the Deck

I'm not sure whose webpage this is, but for a laughable reconstruction using the suits of Swords, Batons, Cups, Coins (the latter two are not on any card): https://cards.old.no/1400-morisca/

I won't bother with what I've tentatively identified as the page of Leafs, since that appears to be the only surviving card of the suit, but here are the three other suits, with missing cards indicated in grayed-out examples from other suits, with a pip example on the right (which again, is only different in the Flower/Sword and Leaf/polo stick suits - the latter not shown); page shown here with an example of the Baton/polo sticks pips with which those court cards must have been associated (simply by a process of subtraction for the other three suits)

Again, turn to the first link at the top of this post to see all available card, but the bottom line is there is but a single 'Unter Knave' - a court card with the suit sign below, marked out from the 'Ober Knaves' have one horse's front leg prancing, in a different position. Why does this card hold a sword, if not in the suit of swords? I think the answer is simple - the well-worn manuscript tradition of depicting the God-denying fool of Palms (“The fool says in his heart, 'There is no God'”, Psalm 14:1; 53:1) holding his club up at God (Giotto's stulticia is basically this), is paralleled by the 'infidel', holding a sword instead. Unfortunately there are no other surviving unter knaves for comparison's sake, but the sign above or below the knave exactly matches that is the later Swiss deck.

What are the ramifications?

This does not 'prove' JvR saw a similar deck, especially since it varies the Maid (what gets called the 'female page' in the CY) for a male Page, but otherwise its an exact match for what he called the "ideal" 15 card suit, forming a deck of 60 cards. Given the deck's early date and pronounced Morisca details (polo sticks and Saracen), its tends towards the probable to my mind.

A final note: Why 60?

JvR has his own reasons for idealizing 60, but he did not create the deck, so the significance of 60 must come from elsewhere...unless of course you want to follow VH and assume JvR actually was the source for novel deck creations (and in this case, a Swiss production for a Spanish market, no less). There is at least one source for which 60 might have been attractive at the time, especially with the inclusion of a queen, which opens up the entire corpus of courtly love: Giovanni Boccaccio's first work, Diana's Hunt, c. 1333-4, has exactly 60 females lead on a hunt lead by Diana (her leadership replaced by the the celestial Venus towards the end), where each of the 60 was named for a real Neapolitan female elites, assuring the work some level of fame. Moreover the 60 females are divided up into four subgroups of 15 for the hunt, making it perfectly suitable for the deck in question, or at least a parallel. The poem was written in terza rima and based on an idea Dante broached in his Vita nuova, for 60 Florentine women (Beatrice of course being the sacred number 9 in his numerology system), but never executed, so Boccaccio ran with it (see Anthony K. Cassell and Victoria Kirkham, Diana's hunt: Caccia di Diana: Boccaccio's first fiction, 1991: 24-25) . This is of course several decades before the advent of cards but Boccaccio dies in 1375 and his fame of course continued to skyrocket. The Angevins in Naples were very involved with the Greek East and could have easily spread Boccaccio's works to Rhodes (Hospitallers) and throughout France of course. The Grand Seneschal of Naples, the ex-Florentine Niccolò Acciaiuoli, was even gifted Greek possessions; and it was his sister who was the dedicatee of Diana's Hunt, Boccaccio feigning the work was not important enough for Queen Joanna. At all events, a reason why 60 and the insertion of a symbolic queen into playing cards. Boccaccio also dedicated his work on the genealogy of the gods to the father of the Cypriot king who lead the raid on Alexandria in 1365. It seemingly all falls together.

Phaeded