To your last points,

Phaeded wrote: 27 Aug 2023, 23:12

But even assuming a standard for the PMB, AS, EE, and CVI (which I do), this "preponderance" all date to after 1451 which is when I see the innovation of expansion. Lumping the CY in with the "preponderance" is an ahistorical rhetorical maneuver to make it look like the CY is the outlier on the same atemporal table, when it precedes all else by a decade and is the earliest surviving exemplar. Again, there is ZERO evidence for 22 trumps before the PMB itself.

All you need is a single reference to 78 cards in the mid-15th century...but it doesn't exist. 70 does.

I remain a 22-trump subjects, A-order fundamentalist because of the evidence for the standard game in the first decade. By the end of 1451, it was played all over Tuscany, it was in the Marches, in Venice, in the Romagna, in Lombardy. The game was loose in the world, and adopting what were to become its traditional forms and play in those regions. The different trump orders prove that they didn't mess around with the number of the subjects, only their ordering in a few places.

Here is the evidence until the end of 1451. Why I think what I think would be clearer to visualize with a chart, but I haven't had the time to do it yet.

The first physical evidence is Rothschild. Their date is hard to pin down, but they bear the unmistakable style of Giovanni dal Ponte, who died before March 1438. The deck has queens, and it has an Emperor. If the date were not controversial, that would be enough to qualify it as a Tarot. If it IS a Tarot, then we have to throw out all of our theories about the influence of Anghiari (you), or the Council (me) on the inspiration for the new game. On the other hand, there is indirect evidence for such a single-Emperor game in the later creation of Fernando della Torre, who studied in Florence in 1432-34, and a 56-card standard pack, i.e. with four court cards including a queen, in Tuscany in Bernardino's sermons of 1425. So the Rothschild cards could be such a single-Emperor game. That is, the Florentines added an Emperor as a trump to their standard cards, and Fernando della Torre, inspired by the game he encountered in Florence in the early 1430s, added an Emperor to the standard Spanish pack in 1450. That's one way to keep the “late invention” of Tarot scenarios alive, and the Rothschild cards can be as old as they (plausibly) like.

So, putting the Rothschild cards to one side...

The first documentary evidence is Giusto Giusti. He says “

naibi a trionfi.” He does not describe the deck. From “naibi” I infer that Florentines knew the game by this name already;

naibi has only one meaning, “playing cards.” From his lack of description I infer that he felt he had no need to, because what it meant was well-known enough. The game is known in both Florence and Rimini-Malatesta territory now.

The second is Ferrara 10 February 1442. There are four decks, they are called “carte da trionfi.” The scribe describes it as the four suits and all the figures. In the many following records of

carte da trionfi in these Este records, this description never occurs again. I infer from this information that 10 February 1442 was the first time the scribe had encountered the game, and wrote a little more than he had to because what it meant was new.

The third is in Ferrara again, the deck sold by Bolognese silk-merchant Marchione Burdochio, 28 July 1442. The game is called “carte da trionfi.” It is cheap, and pre-made. Because of this, I infer it was printed. Where he got it is impossible to know, but Bologna is the first plausible guess, of course.

Around this time, 1440 to 1442, is when the Visconti di Modrone was made in Milan, or Cremona, or wherever the Bembo workshop was. This is secure because Marie-France Lemay, paper curator at the Beinecke, discovered watermarks on the VdM paper that date to between 1439 (watermark on this paper in Reggio Emilia) to 1442 (watermark on this paper in Ferrara).

The next documentary evidence is from 3 January 1444, when two men were arrested for playing “charte a trionfi.” They were playing it in the San Simone district, a poor quarter where the Stinche prison was. We can safely assume that this deck was also a “cheap” kind, or the printed standard type.

The Brambilla deck was probably made in these years, before 1445.

The next documentation is 23 January 1445 in Florence. Two silk dealers (like Marchione Burdochio), Lorenzo di Bartolo and Matteo di Zanobi, sell a standard deck of the “grande” type to another silk-merchant who did business in the Marches. This grande type may have been like the fanti of Swords and Batons, where the Fante of Swords bears an uncanny resemblance to the Charles VI Fante of Swords, but has no expensive pigments or gilding. That is, they come from a deck that repeats what I hold to be the Florentine standard pattern, but cheaply.

For the next documentary reference to the game of Triumphs we have to wait about four years, early 1449 (probably, it could be late 1448), when Jacopo Antonio Marcello is shown how to play the game of Triumphs, and whoever showed it to him gave him the cards. These cards also were not of high quality, “not fit for royalty” as Marcello remarks. After he decided to send them to Isabelle anyway, on Scipio Caraffa's urging, he went looking for cardmakers to buy a high quality deck for her.

The next documentary reference is 1449, Florence, 9 December. The same two silk dealers as in 1445 this time buy six trionfi decks from the painter Giovanni di Domenico. They are really cheap, about 11 soldi each.

22 January 1450 Florence is the next, the same silk dealers sell two cheap Triumph decks (12 soldi each) to a merchant.

Next we go to Ferrara, 16 March 1450, which is a courtly production of Sagramoro, three luxury Triumph decks for Leonello.

Back in Florence 4 April 1450, the same pair of silk dealers acquire three Trionfi decks from Giovanni di Domenico again, even cheaper at 9 soldi each.

In Florence this year, 10 December 1450, the game of Triumphs is permitted to be played, in the company of three other card games, dritta, vinciperdi, and trenta. In this law it is called “trionfo.”

11 December 1450 is the next documentation, Francesco Sforza's letter to his secretary Simonetta “Cichus”) to quickly find him two packs of Triumph cards, of the finest he can find, or if not available any playing cards, of the highest quality there are (naturally). Only four days later Sforza sends another letter thanking him for the cards, but he only says “carte da jocare”, so it is unclear if this means that Simonetta has only found standard playing cards, or Sforza feels he doesn't need to spell out that they were Triumph cards. In any case, Sforza knew that both kinds of cards were ready-made and sold in shops.

Next is early 1451, the town of Gambassi in Florentine territory adopts the exact same permitted card games as Florence, i.e. dritta, vinciperdi, trionfi, trenta. Note that here it is “trionfi”, proving that the game went by both the singular and plural, trionfo and trionfi.

26 January 1451, our familiar silk-dealers acquire two cheap Triumph decks, 14 soldi each, from the artist Antonio di Dino.

12 March 1451, Siena and Sinalunga (Siennese territory) allow the same card games as in Florence.

13 May 1451, same silk dealers sell two cheap “grande” Triumph decks (10.67 soldi as Franco calculated it) to a cassone maker in Venice.

To finish out 1451, 5 August, in Florence again one cheap Triumph deck, 12 soldi, is purchased by a notary.

Most of this is listed with the sources at:

http://trionfi.com/early-trionfi-cards-notes

The evidence of the common game by far overwhelms that of the luxury packs that happen to have survived, either as cards or in documentation. They are rarities compared to the burgeoning regular market for this game, of which the records that Franco studied are just the tip of the iceberg of what artists and cardmakers were making and selling directly.

This common game was a standard product, made and sold along with other cards. Everybody who bought them knew what they were and expected consistency. I cannot believe that the lofty philosophical considerations that you propose were happening in Sforza's court or wherever, about what trumps to put here and there, to remove or change, would have had any effect at all on this regular production and trade. The game was set and established at the beginning, and the luxury productions are modeled on the standard game, not vice-versa. The consistency of the trump subjects among the surviving luxury decks shows what those standard trumps were.

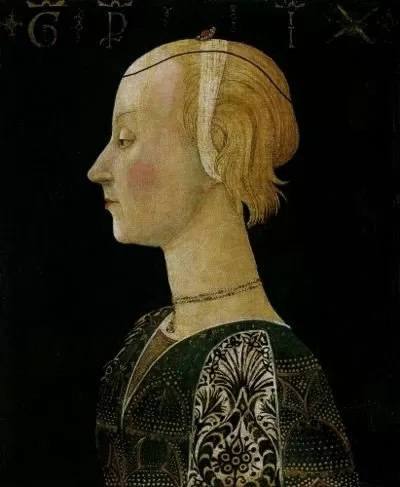

If Ferrara was an early adopter from the very beginning, per that historical possibility I laid out above, it may have accordingly been loathe to accept the innovation made elsewhere (Milan), therefore we encounter a reference to the original 70 card format some 6 years after the innovation of a 78 total card trionfi deck in Milan. Both versions briefly overlapped in time but the centrality and economic might of Milan meant that the 78 card format was to win out, especially since the Sforza dynasty persisted down to the end of the century (and why Malatesta wanted such a deck from Bianca in 1451 - it was novel, and unlike the one he had from Florence since 1440). Ferrara itself eventually following suit per the "Ercole d'Este" deck in 1473.

We don't know how the 70-card deck was composed. Because I can't see how 14 trumps - which ones? - were standard in Ferrara in 1457, I have to accept other explanations for what the "70" means.

If we exclude Charles VI because it appears to be from Apollonio di Giovanni's workshop, and his cassone paintings belong to the same style, which began around 1460, then we have 15 standard trumps accounted for among VdM, Brambilla, PMB, and Catania. If we allow Charles VI as "mid-1450s", because of its close relationship to Catania, which is now dated to around 1450, then every standard trump but the Devil is accounted for. All of this before 1457.

All of this juggling individual trump cards is just so improbable and unnecessary when the obvious, clear, parsimonious, and most Occamic solution is simply that the standard 22 subjects were the original model, all surviving decks have lost some, and the VdM adds three - a coherent single series, not random subjects - to its expanded conception.

Bianca Maria's 14 images have nothing to do with it, and 70 card reference in Ferrara refers to some other configuration, like a deck shortened in the pips. Or it is simply a mistake on the scribe's part.