I finally remembered to order the exhibition catalog to the current exhibition at the Issy museum, Tarots Enluminés: chefs-d'oeuvre de la Renaissance Italienne, 2020-2021 . It came today, and it is a keeper. Lots of stuff I didn't know about.

For example, the Cary-Yale is attributed to Andrea Bembo, Bonifacio's older brother in Brescia, and the PMB 6 added cards to Franco de' Russi, 1465-1470. The Issy Chariot is attributed to a painter in Lombardy, along with the two Warsaw cards and another card from that deck that I haven't seen before. Long essays on the Charles VI (Ada Labriola attributing it to the workshop of Appolonio di Giovanni), the "Alessandro Sforza" (Emilia Maggio now attributing it to the workshop of Lo Scheggia rather than Apollonio, which she used to do), the Petrarch illuminations (by Labriola), the Bembo decks, and the other playing card-themed Lombard painters (both by Roberta Delmoro). It was nice to see that the Visconti-Savoy marriage theme for the CY Love card is still alive, for a deck said done "après 1441". I agree with both it and the other theory, Visconti-Pavia.

Also, the Rothschild cards are attributed to the workshop of Dal Ponte, although that was not new to me. The dating is closer to the truth than it has been; it used to be that Christine Fiorini held it to be early 1420s, while others the 1470s or later. I had guessed 1430-1435. Here it is 1435-1440, probably on the assumptions that it is a tarot and the tarot is no earlier than 1435. But I haven't read it yet.

And of course a fine essay on Marziano by our own Ross Caldwell.

The exhibition itself runs until March 13. On March 11 there will be an all-day colloquium featuring some of the main contributors to the catalog, including Ross. See https://www.museecarteajouer.com/les-expositions/. I presume it will be in French, or I'd inquire about whether there is a zoom option. None is mentioned on the website.

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

2The catalog is excellent, and I can't wait to see the exhibition.

This means that there is still very much the possibility that this deck was not a tarot deck at all, but rather an Imperatori deck (which it could theoretically be even if it is from 1435-1440, of course). This question could perhaps be resolved by the mysterious set of ten cards which Michael Dummett mentioned on p. 89 of Il Mondo e l'Angelo. He wrote that Giuliano Crippa had told him that ten cards in the Bianchi Bonomi collection resembled the Rothschild-Bassano cards, but Dummett had no other information regarding them. If those cards contain trumps, they would be of enormous interest. (And even if they were just suit cards, they would still be of great historical value, especially if they included numeral cards.)

We need to be careful here: The dating and attribution of this deck in the catalog is the work of Ada Labriola, on pages 116-7 in her essay "Les tarots peints à Florence au XVe siècle," one of two excellent contributions from her in this book. It is important to note that she does not unequivocally date the deck to 1435–1440; rather, she says that the deck could be dated to that time. In her discussion, she is effectively reconciling the work of Christina Fiorini and Ross: She agrees with Fiorini (and Bellosi) that the artwork has the style of Giovanni dal Ponte, but appears to agree with Ross that is not likely to be the work of Giovanni dal Ponte directly, but instead the work of someone strongly influenced by him (not necessarily in his workshop, but certainly someone who had at least been trained there). However, this does not mean that the deck must date from after Giovanni dal Ponte's death. Labriola therefore leaves open the possibility that the deck could date from the period 1422-1425 (as hypothesised by Fiorini and by Emanuele Zappasodi in 2016), or presumably from any time between then and 1440.mikeh wrote: 09 Feb 2022, 08:01 Also, the Rothschild cards are attributed to the workshop of Dal Ponte, although that was not new to me. The dating is closer to the truth than it has been; it used to be that Christine Fiorini held it to be early 1420s, while others the 1470s or later. I had guessed 1430-1435. Here it is 1435-1440, probably on the assumptions that it is a tarot and the tarot is no earlier than 1435. But I haven't read it yet.

This means that there is still very much the possibility that this deck was not a tarot deck at all, but rather an Imperatori deck (which it could theoretically be even if it is from 1435-1440, of course). This question could perhaps be resolved by the mysterious set of ten cards which Michael Dummett mentioned on p. 89 of Il Mondo e l'Angelo. He wrote that Giuliano Crippa had told him that ten cards in the Bianchi Bonomi collection resembled the Rothschild-Bassano cards, but Dummett had no other information regarding them. If those cards contain trumps, they would be of enormous interest. (And even if they were just suit cards, they would still be of great historical value, especially if they included numeral cards.)

I plan to be there for the colloquium. I'm very much looking forward to it!The exhibition itself runs until March 13. On March 11 there will be an all-day colloquium featuring some of the main contributors to the catalog, including Ross. See https://www.museecarteajouer.com/les-expositions/. I presume it will be in French, or I'd inquire about whether there is a zoom option. None is mentioned on the website.

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

3Thanks for the correction. I was just going by catalog entries, 19 and 20, pp. 122 and 124, which say "vers 1435-1440"; I wasn't citing Labriola. But yes, now that I've read her, to say "vers 1435-1440" does not capture awhat she says. Like you, I would emphasize the whole range 1422-1440.

It is worth reiterating the importance of not discounting pre-1435. The experts on dal Ponte, notably those who put together the exposition in 2016, give "1425 circa" as the date of the Knight of Swords, but were willing to consider anything as early as 1421. They know the evolution of Dal Ponte's style, from the the beginning to his death, which is why they are so emphatic that it is 1420s. Presumably an assistant would follow the master, if perhaps more cartoonishly. I only wish they had said more.

Zappasodi (p. 128 of the catalog) had suggested that there is a "suggestive" comparison

In response to Zappasodi (she cites the page number, 128), she says:

It seems to me that the Queen is so badly drawn that it is surely by an assistant

It seems to me that the Queen is so badly drawn that it is surely by an assistant

In my own study of the Rothschild cards (http://rothschildcards.blogspot.com/) I picked the fourth panel, because of its "anziani": Also, it seems to me that the old men in the left segment, including the king on the far left, are similar to the Rothschild Emperor and King of Coins. The King of Staves is more similar to the men in the previous panel, although his beard is more like the ones in this one. There are other beards in other works more similar to the Emperor's, as Bellosi pointed out, also of the 1420s.

Also, it seems to me that the old men in the left segment, including the king on the far left, are similar to the Rothschild Emperor and King of Coins. The King of Staves is more similar to the men in the previous panel, although his beard is more like the ones in this one. There are other beards in other works more similar to the Emperor's, as Bellosi pointed out, also of the 1420s.

I don't see "fiery" or "energetic" in dal Ponte's late work, but rather stateliness and dignity. Nothing like that decapitation, for example.

So why should be 1425 not be reasonable? Labriola turns, as she should, to documents about card making. All she says is that Antonio di Dino, who is documented as a card painter in 1446, worked for dal Ponte in 1427. Well, yes, so maybe he was already painting cards. He was one reason why I suggested the early 1430s. In my study I had a fairly involved section on Antonio di Dino, including documentation from 1433 as well as 1427, and that he seems to have been an apprentice, with his main job preparing boards. Huck commented, in our old thread on the Rothschild cards, that his later cards were fairly cheap, so probably not the best. Surely dal Ponte also had assistants in 1421, given that Queen. It's just that there's no evidence of someone who might be learning to make cards then.

Lucky you, to be going to the colloquium. Report back! It is halfway around the world for me, and even if I went, I wouldn't understand much. And thanks for the heads up on the ten Bianchi Bonomi cards. That's worth more follow up, trumps or not.

It is worth reiterating the importance of not discounting pre-1435. The experts on dal Ponte, notably those who put together the exposition in 2016, give "1425 circa" as the date of the Knight of Swords, but were willing to consider anything as early as 1421. They know the evolution of Dal Ponte's style, from the the beginning to his death, which is why they are so emphatic that it is 1420s. Presumably an assistant would follow the master, if perhaps more cartoonishly. I only wish they had said more.

Zappasodi (p. 128 of the catalog) had suggested that there is a "suggestive" comparison

By "World" he meant the card that most of us consider the Page of Coins. I am not sure what he meant by "pointed": maybe noses; or better, something exaggerated about the pointed hats, comparing those in the third panel with that Page (the "World"). Bellosi in his essay gave numerous other comparisons, all to work of the 1420s, scraggly and wiggly beards, like that of the Emperor, among them....tra i profili appuntiti e le barbe increspate dell'Imperatore e del Mondo (?) delle parigine e gli anziani della predella con storie di santa Caterina.

(...between the pointed profiles and the ruffled beards of the Emperor and the World (?) of the Parisians, and the elders of the predella with the stories of Saint Catherine)

In response to Zappasodi (she cites the page number, 128), she says:

The features Zappasodi pointed to (not slender royalty and fiery movements) provide a lower bound of around 1421. Labriola gives us a reproduction of what she takes to be the relevant part of the predella, but it is not easy to make out the details. (In general, I have to say, many of the smaller reproductions in the book tend to be rather poor, needlessly dark.) There are actually four panels, online at https://supernaut.info/2015/01/szepmuve ... -1250-1800. The one she picked is third. Notice the hats and beards:Les figures élancées de l'Empereur (fig. 3), des rois et des reines, les mouvements énergiques et fougueux du valet de bâtons (fig. 4) ou du cavalier d'épées reflètent effectivement des choix stylistiques similaires à ceux faits par Giovanni dal Ponte jusque dans les dernières années de son activité. Il convient néanmoins d'aborder la question de l'attribution des tarots avec davantage de prudence.

(The slender [is that the correct translation?] figures of the Emperor (fig. 3), kings and queens, the energetic and fiery movements of the valet of batons (fig. 4) or the knight of swords effectively reflect stylistic choices similar to those made by Giovanni dal Ponte until the last years of his activity. However, the question of the attribution of the tarot cards should be approached with more caution.)

In my own study of the Rothschild cards (http://rothschildcards.blogspot.com/) I picked the fourth panel, because of its "anziani":

I don't see "fiery" or "energetic" in dal Ponte's late work, but rather stateliness and dignity. Nothing like that decapitation, for example.

So why should be 1425 not be reasonable? Labriola turns, as she should, to documents about card making. All she says is that Antonio di Dino, who is documented as a card painter in 1446, worked for dal Ponte in 1427. Well, yes, so maybe he was already painting cards. He was one reason why I suggested the early 1430s. In my study I had a fairly involved section on Antonio di Dino, including documentation from 1433 as well as 1427, and that he seems to have been an apprentice, with his main job preparing boards. Huck commented, in our old thread on the Rothschild cards, that his later cards were fairly cheap, so probably not the best. Surely dal Ponte also had assistants in 1421, given that Queen. It's just that there's no evidence of someone who might be learning to make cards then.

Lucky you, to be going to the colloquium. Report back! It is halfway around the world for me, and even if I went, I wouldn't understand much. And thanks for the heads up on the ten Bianchi Bonomi cards. That's worth more follow up, trumps or not.

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

4Those are interesting points, regarding the similarities to Giovanni dal Ponte's earlier work rather than his later work.

There are also a few details of the card designs themselves which make them look like they could be from a relatively early date. They have features which are not found in the other painted cards from 15th century Florence, but which do appear in early decks from other regions. This suggests that these features are relatively old and were derived from some early common ancestor of all of those decks, and they were still preserved in the Rothschild cards but then disappeared from cards in Florence in later years.

These features are the gothic decorations in the upper corners, the Jack of Coins with his beard and long tunic, and the "saracen" style shields of the Cavalier of Swords (with similar shields on the King and Queen of Batons).

Gothic upper-corner decorations like those on the Rothschild cards appear on some of the "Budapest" printed cards, some of the trumps of the Rosenwald deck, and some court cards in the Assisi deck. The Rosenwald and Assisi decks were probably both made in Umbria, most likely in Perugia. As far as I recall, nothing like these corner decorations is found on any other Florentine cards until the Minchiate deck appears, when we see decorative squares in the upper corners of many trumps and court cards which are reminiscent of these earlier gothic corner decorations. There are good reasons to believe that the tarot deck on which the Minchiate deck was based must have originally come from somewhere outside Florence (perhaps Arezzo or Siena, or even northern Lazio or Umbria) so this is not strong evidence of any persistence of those gothic decorations on Florentine cards throughout the fifteenth century. In other words, it seems that these gothic corners are a feature that was common to many Italian cards of the early fifteenth century but was dropped by Florentine card designers by the middle of that century.

The Jack of Coins' beard and long tunic, and also those "saracen" shields, are features which are seen in the two decks shown by Tor Gjerde here: http://cards.old.no/1400-morisca/

These decks, which are evidently related (although separated by at least a century in time), probably come from the area of Switzerland and Provence. The saracen shields can be seen in both of them. The older of the two, the Swiss-looking deck (now in the Museo Fournier de Naipes in Spain), includes a bearded jack (of batons), while the other deck has three jacks wearing long tunics. Again, it seems we are dealing with features derived from some early common ancestor of these decks and the Rothschild deck. None of these features are found in any other known cards from Florence except the saracen shields, which appear to be present on the Jack of Swords and Cavalier of Swords in the set of cards in the Bibiolteca Nazionale Universitaria in Turin (these cards are now heavily damaged after a fire in 1904, but images of the intact cards were found and presented by Thierry Depaulis in "Tarots et autres cartes du XVe siècle exposées en 1880 à Turin," The Playing-Card 46 no. 3 (2018): 120–133). The cards in the Turin set have very similar borders to the Rothschild deck, and were therefore probably produced around the same time, or not very many years later; in other words, the Turin cards could also be somewhat earlier than the other surviving Florentine cards.

To sum up my overall impression, the Rothschild cards "look old" to me. Of course, if they were from the late 1430s, they would still be slightly older than most other Florentine cards we have. But they do look as though they could well be even a little older than that—and not just because of the similarities to the work of Giovanni dal Ponte in the 1420s.

There are also a few details of the card designs themselves which make them look like they could be from a relatively early date. They have features which are not found in the other painted cards from 15th century Florence, but which do appear in early decks from other regions. This suggests that these features are relatively old and were derived from some early common ancestor of all of those decks, and they were still preserved in the Rothschild cards but then disappeared from cards in Florence in later years.

These features are the gothic decorations in the upper corners, the Jack of Coins with his beard and long tunic, and the "saracen" style shields of the Cavalier of Swords (with similar shields on the King and Queen of Batons).

Gothic upper-corner decorations like those on the Rothschild cards appear on some of the "Budapest" printed cards, some of the trumps of the Rosenwald deck, and some court cards in the Assisi deck. The Rosenwald and Assisi decks were probably both made in Umbria, most likely in Perugia. As far as I recall, nothing like these corner decorations is found on any other Florentine cards until the Minchiate deck appears, when we see decorative squares in the upper corners of many trumps and court cards which are reminiscent of these earlier gothic corner decorations. There are good reasons to believe that the tarot deck on which the Minchiate deck was based must have originally come from somewhere outside Florence (perhaps Arezzo or Siena, or even northern Lazio or Umbria) so this is not strong evidence of any persistence of those gothic decorations on Florentine cards throughout the fifteenth century. In other words, it seems that these gothic corners are a feature that was common to many Italian cards of the early fifteenth century but was dropped by Florentine card designers by the middle of that century.

The Jack of Coins' beard and long tunic, and also those "saracen" shields, are features which are seen in the two decks shown by Tor Gjerde here: http://cards.old.no/1400-morisca/

These decks, which are evidently related (although separated by at least a century in time), probably come from the area of Switzerland and Provence. The saracen shields can be seen in both of them. The older of the two, the Swiss-looking deck (now in the Museo Fournier de Naipes in Spain), includes a bearded jack (of batons), while the other deck has three jacks wearing long tunics. Again, it seems we are dealing with features derived from some early common ancestor of these decks and the Rothschild deck. None of these features are found in any other known cards from Florence except the saracen shields, which appear to be present on the Jack of Swords and Cavalier of Swords in the set of cards in the Bibiolteca Nazionale Universitaria in Turin (these cards are now heavily damaged after a fire in 1904, but images of the intact cards were found and presented by Thierry Depaulis in "Tarots et autres cartes du XVe siècle exposées en 1880 à Turin," The Playing-Card 46 no. 3 (2018): 120–133). The cards in the Turin set have very similar borders to the Rothschild deck, and were therefore probably produced around the same time, or not very many years later; in other words, the Turin cards could also be somewhat earlier than the other surviving Florentine cards.

To sum up my overall impression, the Rothschild cards "look old" to me. Of course, if they were from the late 1430s, they would still be slightly older than most other Florentine cards we have. But they do look as though they could well be even a little older than that—and not just because of the similarities to the work of Giovanni dal Ponte in the 1420s.

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

5Labriola's main subject, of course, is the Charles VI, which she attributes to the workshop of Apollonio di Giovanni. The idea is not new; she says that according to Depaulis Ross suggested it many years ago; I myself advocated it, based on commonalities in the backgrounds, in 2018 (viewtopic.php?p=20310#p20310), along with the parallel attribution of the Catania cards to Lo Scheggia (which Huck had already formulated). But it always helps to have new arguments.

Here is what she says (pp. 120-121):

So we have four examples, plus the suggestion of more, from other Apollonio Trionfi illustrations. I have a hard time seeing similarities when the details aren't right next to each other, so I've made collages.

First, the Love card. Clockwise from top left, they are first, the young people of the Love card, then the relevant detail of Labriola's example from the Aeneid illuminations (I got it from a screenshot of the illumination at https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_10649/?sp=5), then below those a detail from an Apollonio cassone of the Story of Esther that I thought was at least as close, as far as the headpieces (from the Metropolitan Museum site).

Second, the Charioteer. Below, to the right, is the detail she uses for comparison. The match is not that close, in my opinion. The weapon is different, and so is the hat, as well as his posture. But the face is similar. And I have found hats in other Apollonio illustrations that seem to me close to that on the Charioteer, on the left nearest the Chariot card.

Third is the Fool, i.e. the children underneath.

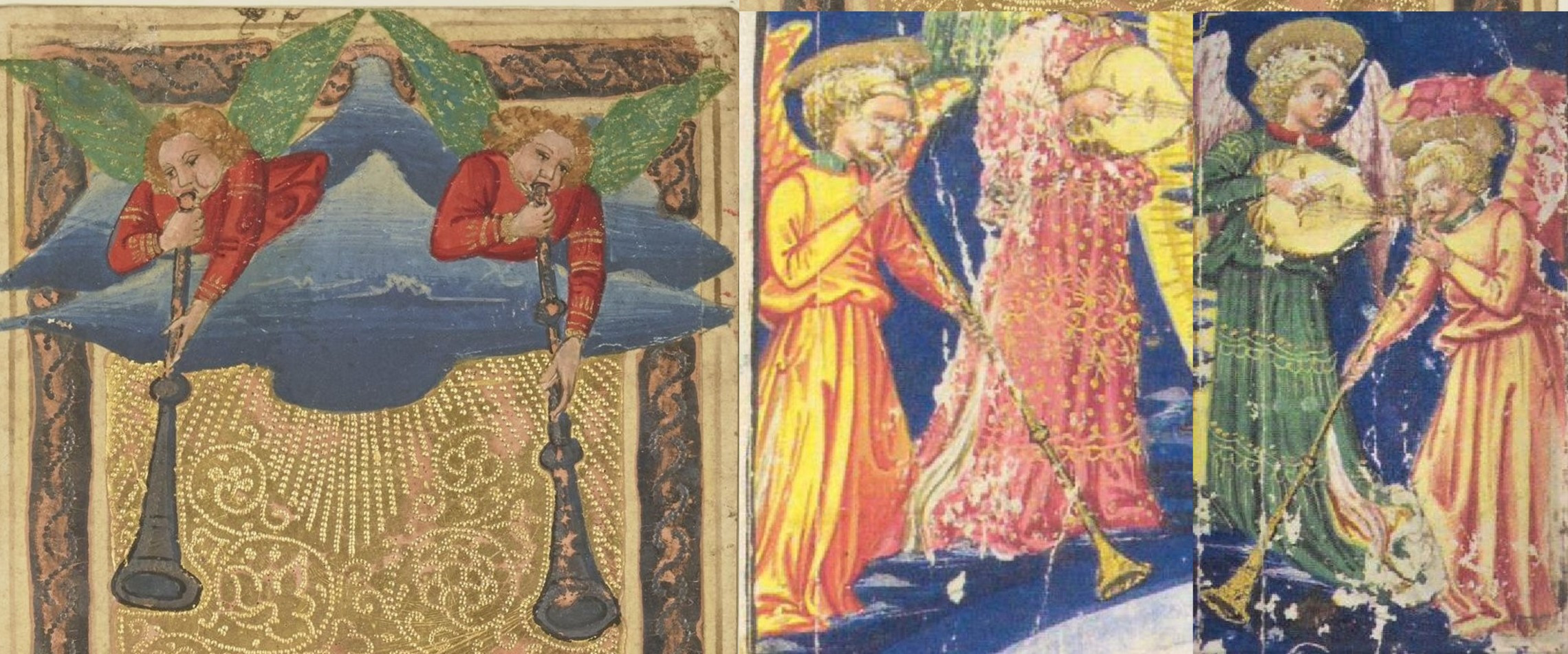

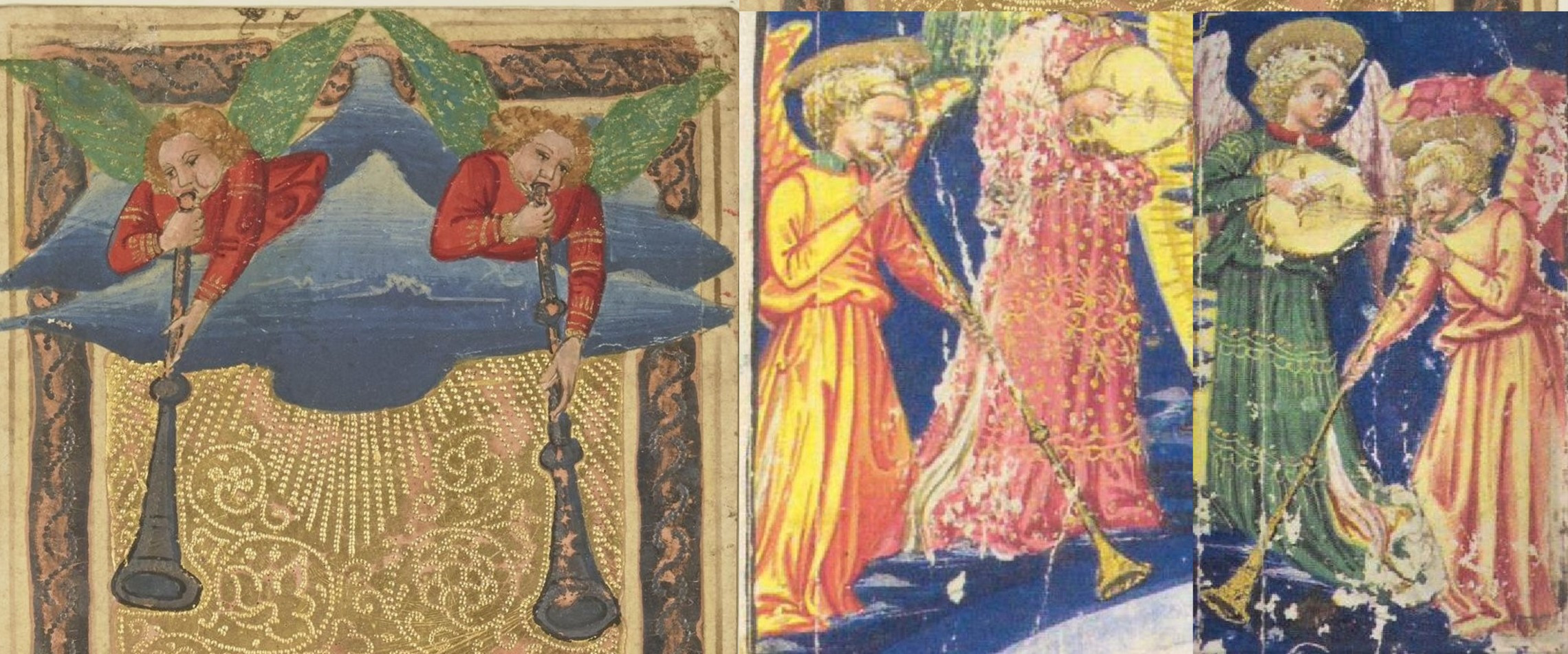

Fourth, the trumpeters, isolating the relevant details from the card and the Apollonio Triumph.

Finally, I want to add one more, an example of "the prominent red mouths, the accentuated expressiveness," namely the two astronomers and a couple of scenes from the Aeneid series.

I will end this post with a few questions. First, what does she mean by "square shapes surrounded by a thick line" (formes carrées entourées d'un trait épais)? What are some examples? Perhaps someone can help me. Second, what similarities in Apollonio can be found for other trump cards in the series? And third, are there other artists or milieux that also have similarities, perhaps closer and perhaps different, and if so, how are we to know which workshop it is that did the cards? I will work on these latter two questions in posts to follow.

Here is what she says (pp. 120-121):

À mon avis, le jeu de la BnF présente des affinités avec les oeuvres réalisées par Apollonio di Giovanni vers 1460 ou peu après, et peut être confronté notamment avec son activité dans le domaine de l'illustration de livres. Les types et les physionomies des personnages (les formes carrées entourées d'un trait épais, les bouches rouges proéminentes, l'expressivité accentuée) font écho à ceux peints par Apollonio dans son manuscrit enluminé le plus fastueux, qui contient les trois poèmes de Virgile (les Bucoliques, les Géorgiques et l' Énéide)31. À titre d'exemple, citons les dames du cortège figurant sur la carte de l'Amoureux, identiques aux élégantes du manuscrit virgilien (f. 72r) (fig. 9), le soldat debout sur le Chariot peu différent de la représentation d'Achille traînant le corps d'Hector (f. ) (cat. 25, fig. 10), et les

___________

31. Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana, Ricc. 492.

jeunes gens se moquant du Fou qui rappellent le serviteur visible au premier plan du Banquet de Didon (f. 75r) (fig.6,11) 32. Les comparaisons peuvent s'étendre à un autre manuscrit des Triomphes de Pétrarque peint par Apollonio33. Parmi les nombreuses analogies que l'on peut relever, on notera la similitude entre les visages des anges musiciens avec le tuba du Jugement et ceux de l'enluminure du Triomphe de l'Éternité (f. 46r) (fig. 7, 12) 34. Le peintre des cartes à jouer est vraisemblablement un collaborateur d'atelier.

____________

32. Lazzi 2006 ["Enea sull 'Arno. il Virgilio riccardiano" Alumina, IV, No. 13, p.44-51]; Labriola 2012 ["Da Padova a Firenze: l'illustrazioni dei Trionfi," dans Ida Givanna Rao (dir.), Francesco Petrarca, I Trionfi: Commentario, Castelveltro di Modena, pp. 59-115], p. 105, fig. 76, 77, 112. Le manuscrit virgilien fut signé par le copiste florentin 'Nicolaus Riccius Spinosus», c'est-à-dire Niccole de' Ricci.

33. Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana, Ricc.1129.

34. Le manuscrit Ricc. 1129 a été rapproché de la commande du Florentin Agnolo di Lorenzo della Stufa, riche marchand et fidèle allié des Médicis, entre 1459 et 1461: Callmann 1974, P. 35-36. 58, n°13. Son écriture a été attribuée au copiste anonyme « de l'Eusèbe de Barcelone ». Voir de la Mare 1985a, 1, p. 541.

(In my opinion, the BnF deck presents affinities with the works produced by Apollonio di Giovanni around 1460 or shortly after, and can be compared in particular with his activity in the field of book illustration. The types and physiognomies of the characters (the square shapes surrounded by a thick line, the prominent red mouths, the accentuated expressiveness) echo those painted by Apollonio in his most sumptuous illuminated manuscript, which contains the three poems of Virgil (the Bucolics, the Georgics and the Aeneid)31. By way of example, let us cite the ladies of the cortege appearing on the card of The Lovers, identical to the elegant ladies of the Virgilian manuscript (f. 72r) (fig. 9), the soldier standing on the Chariot little different from the representation of Achilles dragging the body of Hector (f. 70r) (cat. 25, fig. 10), and the

___________

31. Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana, Ricc. 492.

young people mocking the Fool who recall the servant visible in the foreground of the Banquet of Dido (f. 75r) (fig.6,11)32. The comparisons can be extended to another manuscript of the Triumphs of Petrarch painted by Apollonio33. Among the many analogies that can be noted, note the similarity between the faces of the musical angels with the trumpet of Judgment and those of the illumination of the Triumph of Eternity (f. 46r) (fig. 7, 12) 34. The painter of the playing cards is probably a workshop collaborator.

____________

32. Lazzi 2006 ["Enea sull 'Arno. il Virgilio riccardiano" Alumina, IV, No. 13, p.44-51]; Labriola 2012 ["Da Padova a Firenze: l'illustrazioni dei Trionfi," in Ida Givanna Rao (ed.), Francesco Petrarca, I Trionfi: Commentario, Castelveltro di Modena, pp. 59-115], p. 105, fig. 76, 77, 112. The Virgilian manuscript was signed by the Florentine copyist 'Nicolaus Riccius Spinosus', i.e. Niccole de' Ricci.

33. Florence, Biblioteca Riccardiana, Ricc.1129.

34. The Ricc. manuscript 1129 was related to the order of the Florentine Agnolo di Lorenzo della Stufa, a wealthy merchant and faithful ally of the Medici, between 1459 and 1461: Callmann 1974, pp. 35-36. 58, no.13.The writing has been attributed to the anonymous copyist “of Eusebius of Barcelona”. See de la Mare 1985a, 1, p. 541.)

So we have four examples, plus the suggestion of more, from other Apollonio Trionfi illustrations. I have a hard time seeing similarities when the details aren't right next to each other, so I've made collages.

First, the Love card. Clockwise from top left, they are first, the young people of the Love card, then the relevant detail of Labriola's example from the Aeneid illuminations (I got it from a screenshot of the illumination at https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_10649/?sp=5), then below those a detail from an Apollonio cassone of the Story of Esther that I thought was at least as close, as far as the headpieces (from the Metropolitan Museum site).

Second, the Charioteer. Below, to the right, is the detail she uses for comparison. The match is not that close, in my opinion. The weapon is different, and so is the hat, as well as his posture. But the face is similar. And I have found hats in other Apollonio illustrations that seem to me close to that on the Charioteer, on the left nearest the Chariot card.

Third is the Fool, i.e. the children underneath.

Fourth, the trumpeters, isolating the relevant details from the card and the Apollonio Triumph.

Finally, I want to add one more, an example of "the prominent red mouths, the accentuated expressiveness," namely the two astronomers and a couple of scenes from the Aeneid series.

I will end this post with a few questions. First, what does she mean by "square shapes surrounded by a thick line" (formes carrées entourées d'un trait épais)? What are some examples? Perhaps someone can help me. Second, what similarities in Apollonio can be found for other trump cards in the series? And third, are there other artists or milieux that also have similarities, perhaps closer and perhaps different, and if so, how are we to know which workshop it is that did the cards? I will work on these latter two questions in posts to follow.

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

6I am now reading more of Labriola's article. First is the Rothschild. She says:

Whether the globe in the Emperor's hand is meant as a florin or as a symbol of the empire does not seem to me clear. However, once it is established by other means that the artist was a Florentine, then it tends to support that attribution. It is Bellosi's merit to have drawn the connection to dal Ponte.

Whether the globe in the Emperor's hand is meant as a florin or as a symbol of the empire does not seem to me clear. However, once it is established by other means that the artist was a Florentine, then it tends to support that attribution. It is Bellosi's merit to have drawn the connection to dal Ponte.

I want in fact to draw one more connection between dal Ponte and the cards. If you look at the 1421 predella showing the queen with Saint Catherine, the length of the torso is too long. You can see why by comparing it to another queen of batons, from the Brera-Brambilla (Bembo workshop, 1440s), in which the upper legs descend from the hip to the knee at an angle, as seen through the clothes. In the dal Ponte and Rothschild card, the upper leg isn't shown at an angle, so that the hip appears too low in both cases. Perhaps it is the same assistant at work in both places, I don't know.

Then from the Rothschild to the Catania it is fairly clear; one might wonder if the same artist didn't do both the Palermo Empress, considered part of the Catania set, and the Rothschild Emperor. The only reason I can see for saying no has to do with the other cards in the Catania - i.e. Temperance, which shows the style of Scheggia - and in the Rothschild - where the knight of swords in particular shows the style of dal Ponte. Then the relation to the Charles VI is stylistically a rather big jump, from Late International Gothic to Renaissance, if only in the degree of naturalism, better shading in the ChVI and boys as opposed to miniature adults.

But how do we know that it was Apollonio's workshop that did the Charles VI and Scheggia's the Catania? Why not one workshop for both, since so many of the cards in the two decks look so similar: the Old Man (https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-yko2uoO14Is/ ... VITime.jpg) and the World (https://2.bp.blogspot.com/-r7voo9kBNbs/ ... VIFame.jpg), especially. Here is what Labriola says:

https://www.magnoliabox.com/products/tr ... -xal194162

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File ... irenze.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... dimari.jpg

Unfortunately she doesn't say what it is about these paintings by Scheggia that remind one of the Catania-Palermo cards as opposed to the Charles VI cards. The drawings of the faces show variations, but it is the same variations in both artists. In the Charles VI, look at the virtues and then the Page, for example. (It could be that different artists were at work, including the same artist in different workshops!)

Huck once pointed to the difference that the Catania-Palermo heads were more blond and curly, as opposed to the Charles VI's darker heads: viewtopic.php?p=17326&sid=235fb7e51bdb8 ... 482#p17326. I also notice more use of red on the heads, especially around the mouths, in the Charles VI. These same differences show up in Scheggia's and Apollonio's art, for similar age and gender. Older men are darker in both artists (for Scheggia see his famous birthtray). Perhaps that is what she has in mind; but I am only guessing. It didn't occur to Huck and me that such differences would be a sign of a different workshop, but maybe it is. And as Huck noticed long ago (and also in the last mentioned post) the card that has the closest affinity to Scheggia is the "Stagrider".

For myself, what strengthens the rejection of Scheggia's as the workshop of the Charles VI is the features of the cards that can be found in Apollonio and not Scheggia. For trumpeting angels (or humans), Apollonio's are a good match; Scheggia's aren't. Below are the only examples by him I could find: I also cannot find hats precisely like the one on the Charles VI Charioteer's head in Scheggia, rectangular shaped as opposed to slightly circular (concave) on top or upside down conical, like on the Catania. I do find the rectangular shaped ones in Apollonio. Scheggia's women's caps likewise are a bit different, lacking the dots on them that we see on the Love card and in Apollonio. These are very fine details, admittedly. Perhaps there is something more obvious that I have missed.

I also cannot find hats precisely like the one on the Charles VI Charioteer's head in Scheggia, rectangular shaped as opposed to slightly circular (concave) on top or upside down conical, like on the Catania. I do find the rectangular shaped ones in Apollonio. Scheggia's women's caps likewise are a bit different, lacking the dots on them that we see on the Love card and in Apollonio. These are very fine details, admittedly. Perhaps there is something more obvious that I have missed.

This is sometimes taken as definitive that the Rothschild is Florentine. It seems to me that Emilia Maggio showed fairly well a few years ago that the fleur de lys does not necessarily symbolize the currency of Florence, but rather the office which the emperor holds. Here are four images of the fleur-de-lys, one of an actual florin, but I don't know of what date, two others just signifying the empire (one from the Borso d'Este Bible, the other from Maggio's article, p. 261) the Emperor Mansa Musa, from the Catalan Atlas, 1375, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris (cote MSS. ESP. 30)Dans le jeu Rothschild, l'Empereur tient dans samain gauche un globe où figure un florin d'or, monnaie symbole de Florence (fig.3], tandis que danscelui réparti entre le musée municipal de Catane et le Palazzo Abatellis de Palerme apparaît un emblèmedistinctif non florentin.

(In the Rothschild deck, the Emperor holds in his left hand a globe on which appears a gold florin, the currency symbol of Florence (fig.3], while in the one distributed between the municipal museum of Catania and the Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo appears a distinctive non-Florentine emblem.)

I want in fact to draw one more connection between dal Ponte and the cards. If you look at the 1421 predella showing the queen with Saint Catherine, the length of the torso is too long. You can see why by comparing it to another queen of batons, from the Brera-Brambilla (Bembo workshop, 1440s), in which the upper legs descend from the hip to the knee at an angle, as seen through the clothes. In the dal Ponte and Rothschild card, the upper leg isn't shown at an angle, so that the hip appears too low in both cases. Perhaps it is the same assistant at work in both places, I don't know.

Then from the Rothschild to the Catania it is fairly clear; one might wonder if the same artist didn't do both the Palermo Empress, considered part of the Catania set, and the Rothschild Emperor. The only reason I can see for saying no has to do with the other cards in the Catania - i.e. Temperance, which shows the style of Scheggia - and in the Rothschild - where the knight of swords in particular shows the style of dal Ponte. Then the relation to the Charles VI is stylistically a rather big jump, from Late International Gothic to Renaissance, if only in the degree of naturalism, better shading in the ChVI and boys as opposed to miniature adults.

But how do we know that it was Apollonio's workshop that did the Charles VI and Scheggia's the Catania? Why not one workshop for both, since so many of the cards in the two decks look so similar: the Old Man (https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-yko2uoO14Is/ ... VITime.jpg) and the World (https://2.bp.blogspot.com/-r7voo9kBNbs/ ... VIFame.jpg), especially. Here is what Labriola says:

Here are the paintings she is referring to:La représentation des personnages se caractérise par unesolide répartition des volumes aux contours simplifiés ; la définition de l'espace y est cohérente et mesurée, comme sur les cartes qui illustrent le Chariot et le Monde, par exemple (fig.5). Ces images trouvent un équivalent dans la peinture florentine autour de 1450 ou peu après, et de manière particulière, à mon sens, dans les œuvres de Lo Scheggia: nous citerons ainsi les Triomphes déjà mentionnés (fig.1) et le Jeu du civettino du musée du palais Davanzati [cat.27], sans oublier l'une de ses peintures les plus célèbres, le coffre Adimari avec une Scène de danse (Florence, Galleria dell'Accademia)27.

The representation of the characters is characterized by a solid distribution of volumes with simplified contours; the definition of space is coherent and measured there, as on the cards illustrating the Chariot and the World, for example (fig.5). These images find an equivalent in Florentine painting around 1450 or shortly after, and in a particular way, in my opinion, in the works of Lo Scheggia: we will thus cite the Triumphs already mentioned (fig.1) and the Game of Civettino of the Davanzati Palace Museum [cat.27], not forgetting one of his most famous paintings, the Adimari Chest with a Dance Scene (Florence, Galleria dell'Accademia)27.)

__________

27. Sbaraglio 2010, p. 162-165, cat. no. 1

https://www.magnoliabox.com/products/tr ... -xal194162

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File ... irenze.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... dimari.jpg

Unfortunately she doesn't say what it is about these paintings by Scheggia that remind one of the Catania-Palermo cards as opposed to the Charles VI cards. The drawings of the faces show variations, but it is the same variations in both artists. In the Charles VI, look at the virtues and then the Page, for example. (It could be that different artists were at work, including the same artist in different workshops!)

Huck once pointed to the difference that the Catania-Palermo heads were more blond and curly, as opposed to the Charles VI's darker heads: viewtopic.php?p=17326&sid=235fb7e51bdb8 ... 482#p17326. I also notice more use of red on the heads, especially around the mouths, in the Charles VI. These same differences show up in Scheggia's and Apollonio's art, for similar age and gender. Older men are darker in both artists (for Scheggia see his famous birthtray). Perhaps that is what she has in mind; but I am only guessing. It didn't occur to Huck and me that such differences would be a sign of a different workshop, but maybe it is. And as Huck noticed long ago (and also in the last mentioned post) the card that has the closest affinity to Scheggia is the "Stagrider".

For myself, what strengthens the rejection of Scheggia's as the workshop of the Charles VI is the features of the cards that can be found in Apollonio and not Scheggia. For trumpeting angels (or humans), Apollonio's are a good match; Scheggia's aren't. Below are the only examples by him I could find:

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

7It also requires more defense that these cards, all three decks, are Florentine as opposed to Bologna or Ferrara, the other places that in the past were suggested. The "florin" on the Rothschild Emperor is not enough. Nor is the similarity in design, because if a set is purchased in Ferrara, it is not hard to copy the design if the commissioner wants that done. We know that Imperatori decks were purchased from Florence by the d'Este court, in 1423 and 1432. So even if the Rothschild and Catania cards were made in Florence, the Charles VI could be made in Ferrara or Bologna, at least so far. Nor are the palle by themselves a good argument, because that design is seen in contexts with no apparent connection to the Medici. See Huck's post at viewtopic.php?p=24364#p24364 and mine at viewtopic.php?p=18665#p18665, In the case of the cloth preserved in Venice, the Medici connection is only an assumption.

On the other hand, it seems to me that if the Charles VI were made for the Estense, Borso in particular (shown wearing a similar hat in the Schifanoia April fresco), he wouldn't have wanted a design on it well-known for its association to the Medici.

And there are other reasons for doubting it comes from Emilia-Romagna, even assuming the use of Florentine models. For one thing, the rock on the Old Man card is in a style seen in numerous Florentine contexts, especially Apollonio's, but the Emilians liked to give it a more interesting colors than just gray (Apollonio is second from right, Borso Bible far right):

Another background consideration is architecture. Cosimo started the Medici Palace in 1444 and finished enough for Gozzoli to safely put his fresco in the chapel by 1459. It initiated the "rustication" style for the masonry of the outer wall, seen earlier on the Palazzo Vecchio and a few others but not fashionable in new buildings until Cosimo used it. The Pazzi did their palace in the same way. In both Scheggia (top left) and Apollonio (bottom left) this style is evident, as well as, in simplified form, the Charles VI Tower card. Emilian exteriors were either plain or simply smooth blocks, not protruding out as seen on the Tower card, as in the example at right. Moreover, it is enough to compare Emilian images apparently taken from the designs on the Charles VI or other cards with Apollonio to see how different the Emilian style is, even when the pose is the same (on the left Apollonio, from his rape of the Sabine women; on the right, from Borso's Bible).

Moreover, it is enough to compare Emilian images apparently taken from the designs on the Charles VI or other cards with Apollonio to see how different the Emilian style is, even when the pose is the same (on the left Apollonio, from his rape of the Sabine women; on the right, from Borso's Bible).

And:

And:

I pick Borso d'Este's Bible for my Emilian examples because it brought together a large number of illuminators in one place.

I pick Borso d'Este's Bible for my Emilian examples because it brought together a large number of illuminators in one place.

The Schifanoia Hall of the Months indeed has a different style, closer to that of the Charles VI. While Cossa's April fresco is certainly as expressive and beautiful as anything in the Charles VI (or more so), the women's caps (as opposed to the double horns, a style shared by both Florence and Ferrara) are quite differently portrayed, and the clothing lacks the shading characteristic of Ferrara. Clockwise below, from the upper right to the upper left: the Love card, three from Apollonio (Florence), and two from the Schifanoia April fresco (Ferrara): The Schifanoia details are from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... _Venus.jpg.

The Schifanoia details are from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... _Venus.jpg.

On the other hand, it seems to me that if the Charles VI were made for the Estense, Borso in particular (shown wearing a similar hat in the Schifanoia April fresco), he wouldn't have wanted a design on it well-known for its association to the Medici.

And there are other reasons for doubting it comes from Emilia-Romagna, even assuming the use of Florentine models. For one thing, the rock on the Old Man card is in a style seen in numerous Florentine contexts, especially Apollonio's, but the Emilians liked to give it a more interesting colors than just gray (Apollonio is second from right, Borso Bible far right):

Another background consideration is architecture. Cosimo started the Medici Palace in 1444 and finished enough for Gozzoli to safely put his fresco in the chapel by 1459. It initiated the "rustication" style for the masonry of the outer wall, seen earlier on the Palazzo Vecchio and a few others but not fashionable in new buildings until Cosimo used it. The Pazzi did their palace in the same way. In both Scheggia (top left) and Apollonio (bottom left) this style is evident, as well as, in simplified form, the Charles VI Tower card. Emilian exteriors were either plain or simply smooth blocks, not protruding out as seen on the Tower card, as in the example at right.

The Schifanoia Hall of the Months indeed has a different style, closer to that of the Charles VI. While Cossa's April fresco is certainly as expressive and beautiful as anything in the Charles VI (or more so), the women's caps (as opposed to the double horns, a style shared by both Florence and Ferrara) are quite differently portrayed, and the clothing lacks the shading characteristic of Ferrara. Clockwise below, from the upper right to the upper left: the Love card, three from Apollonio (Florence), and two from the Schifanoia April fresco (Ferrara):

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

8You forgot the numbers written on the Charles VI and Catania cards. The numbering on both is the Florentine order in the Minchiate deck, except of course that these decks could never have been used for Minchiate, which means the numbering must date from a time after the mnemonic Florentine strambotto (published ca. 1500 but probably at least ten years older than that, because it must predate the numbering of the decks, which in the case of the Rosenwald was happening by around 1500) but before Minchiate ousted the 78-card deck in Tuscany in the 16th century.mikeh wrote: 27 Feb 2022, 09:48 It also requires more defense that these cards, all three decks, are Florentine as opposed to Bologna or Ferrara, the other places that in the past were suggested. The "florin" on the Rothschild Emperor is not enough. Nor is the similarity in design, because if a set is purchased in Ferrara, it is not hard to copy the design if the commissioner wants that done. We know that Imperatori decks were purchased from Florence by the d'Este court, in 1423 and 1432. So even if the Rothschild and Catania cards were made in Florence, the Charles VI could be made in Ferrara or Bologna, at least so far. Nor are the palle by themselves a good argument, because that design is seen in contexts with no apparent connection to the Medici. See Huck's post at viewtopic.php?p=24364#p24364 and mine at viewtopic.php?p=18665#p18665, In the case of the cloth preserved in Venice, the Medici connection is only an assumption.

Given that the trump order written on the cards was not the earliest one used in Florence, it is unlikely that the same numbering was coincidentally used anywhere beyond Tuscany as well, so we can be reasonably confident that the numbers were written onto these cards in Tuscany sometime between the late 15th century and the early 16th century, at a time when regular decks had begun to be made with numbers printed on the trumps, but before the dominance of Minchiate.

It seems extremely unlikely that the cards would have been made in Ferrara or Cremona or somewhere like that and then brought to Tuscany later (and then numbered), if only because we know that Florence itself was producing substantial numbers of luxury cards of this type, so they would have surely had no need to import them from so far afield.

The substantial production of Florence is in itself another reason to support an attribution of these cards to Florence: They were making so many of them that we would expect a few to have survived, and these are the only possible candidates, along with the related non-tarot cards in the Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria of Turin, the Museo Correr in Venice and the Louvre. On the other hand, it would be rather surprising if the small-scale production of luxury cards in Ferrara were to have left so many survivors.

All things considered, I am quite satisfied with the Florentine attribution of these three decks and see no reason to doubt it.

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

9Slight correction: I do of course mean "the Florentine order in the Minchiate deck if the 20 additional trumps were not there," i.e. I am not saying that the Moon, Sun, World, and Angel in the Charles VI deck were numbered 37, 38, 39, 40...Nathaniel wrote: 28 Feb 2022, 08:57 The numbering on both is the Florentine order in the Minchiate deck,

Re: Issy Exhibition (until March 13, '22) Catalog

10I am sorry for not noticing your comments on the Rothschild, Nathaniel (viewtopic.php?p=24545#p24545). Those were good points. I have raised some of them at http://rothschildcards.blogspot.com/. There is one thing I didn't understand. You wrote:

Nathaniel wrote,

Whether there are reasons for thinking the Charles VI was made elsewhere, or for a commission elsewhere, I do not know. Artists and artisans trained in Florence went to Bologna in those years, to satisfy the desires there for Florentine-style household goods (I don't remember where I read that, perhaps Ady's book). Costumes have been mentioned in favor of a Ferrarese commission (by Klein at least, although I haven't read him, and something is forthcoming by Elisabetta Gnignera in the revised book, now also translated into English, on tarocchi focusing on Bologna that Andrea and I are working on), but I do not understand the argument.

I did not follow your argument that the numbers on the Charles VI indicate that they were put there later than the Strambotto. That they are the same as those of minchiate does not seem to me to mean anything in itself, because a card game called minchiate is documented in 1466 (Pulci to Lorenzo) and is made a legally allowed game in 1477 (http://naibi.net/A/426-FI1473-Z.pdf, trans. at http://pratesitranslations.blogspot.com ... -laws.html). It does not have to have had all 97 cards by then either. A term for a game is defined by continuity of use over time for an object that may change in character. All that is important is that the games be different, so that they are not simply names for the same game. The presence of theologicals and Prudence could be enough, if that is the way it went. In that sense, even the Cary-Yale might be a minchiate. We don't know how old the term is, even if 1466 is the earliest so far. Already in c. 1440 a satirical poet in Florence, given to double meanings, is speaking of "minchiatar" in the same breath as "triomphi",viewtopic.php?p=15174#p15174.

But again, I do not disagree that the order of the numbers on the Charles VI is later than that of the Strambotto. My thinking is that the Bolognese order was first (with the Chariot after the virtues, as for Croce 1602), which then went to Florence, which changed the order of the virtues and at some point removed a papa, and that order was later supplanted by the minchiate order, reversing the position of Chariot and Wheel. This line of thought seems to me a bit insecure, so I am interested in what yours is.

I need to correct one earlier mistake. "Imperatori" decks are documented as made in Florence for Ferrara, besides 1423, also in 1434, not 1432 (http://naibi.net/A/55-IMPER-Z.pdf).

Please explain. That might also help to clear up some of my confusion about your most recent post, regarding minchiate.There are good reasons to believe that the tarot deck on which the Minchiate deck was based must have originally come from somewhere outside Florence (perhaps Arezzo or Siena, or even northern Lazio or Umbria) so this is not strong evidence of any persistence of those gothic decorations on Florentine cards throughout the fifteenth century.

Nathaniel wrote,

I am not denying that the Charles VI was made in Florence. I said "at least so far", meaning so far in my presentation. It is merely that the numbers by themselves don't show that it was made there. A deck can be made in one place (say, Bologna) for another place (say, Ferrara) and then sold or given as a present later to someone in another place (Florence), where the numbers are added. The numbers on the Charles VI and Catania do suggest prima facie that the deck was for Florence, and there are other reasons for thinking so as well, as I go on to say. I wanted to support Labriola's emphasis on identifying the artists' milieu and style. I could add that it does not seem to me likely that the Ferrara court would commission a Chariot cad with a design already well known to be associated with the Medici. Also, the Catania and Charles VI seem different enough to have been different commissions. If so, it is a strange coincidence that they both would have been sold or given to people in Florence independently, who put the Florentine numbers on.You forgot the numbers written on the Charles VI and Catania cards. The numbering on both is the Florentine order in the Minchiate deck, except of course that these decks could never have been used for Minchiate, which means the numbering must date from a time after the mnemonic Florentine strambotto (published ca. 1500 but probably at least ten years older than that, because it must predate the numbering of the decks, which in the case of the Rosenwald was happening by around 1500) but before Minchiate ousted the 78-card deck in Tuscany in the 16th century.

Whether there are reasons for thinking the Charles VI was made elsewhere, or for a commission elsewhere, I do not know. Artists and artisans trained in Florence went to Bologna in those years, to satisfy the desires there for Florentine-style household goods (I don't remember where I read that, perhaps Ady's book). Costumes have been mentioned in favor of a Ferrarese commission (by Klein at least, although I haven't read him, and something is forthcoming by Elisabetta Gnignera in the revised book, now also translated into English, on tarocchi focusing on Bologna that Andrea and I are working on), but I do not understand the argument.

I did not follow your argument that the numbers on the Charles VI indicate that they were put there later than the Strambotto. That they are the same as those of minchiate does not seem to me to mean anything in itself, because a card game called minchiate is documented in 1466 (Pulci to Lorenzo) and is made a legally allowed game in 1477 (http://naibi.net/A/426-FI1473-Z.pdf, trans. at http://pratesitranslations.blogspot.com ... -laws.html). It does not have to have had all 97 cards by then either. A term for a game is defined by continuity of use over time for an object that may change in character. All that is important is that the games be different, so that they are not simply names for the same game. The presence of theologicals and Prudence could be enough, if that is the way it went. In that sense, even the Cary-Yale might be a minchiate. We don't know how old the term is, even if 1466 is the earliest so far. Already in c. 1440 a satirical poet in Florence, given to double meanings, is speaking of "minchiatar" in the same breath as "triomphi",viewtopic.php?p=15174#p15174.

But again, I do not disagree that the order of the numbers on the Charles VI is later than that of the Strambotto. My thinking is that the Bolognese order was first (with the Chariot after the virtues, as for Croce 1602), which then went to Florence, which changed the order of the virtues and at some point removed a papa, and that order was later supplanted by the minchiate order, reversing the position of Chariot and Wheel. This line of thought seems to me a bit insecure, so I am interested in what yours is.

I need to correct one earlier mistake. "Imperatori" decks are documented as made in Florence for Ferrara, besides 1423, also in 1434, not 1432 (http://naibi.net/A/55-IMPER-Z.pdf).