So now I am revisiting the Robertet (of Moulins, France) images in the light of Ziegler and others, in this post focusing on the Triumph of Love. I'm going to review what Ziegler has to say and add a few things. My topic is the hypothesis that the Robertet Triumphs (accepting Ziegler's 1490-1500 dating) are based on a pre-1447 tradition of Petrarch

Trionfi illustrations now lost, perhaps relating in turn to a similar tradition in certain tarot images.

Here are my screenshots of Ziegler's commentary (in German) on the Robertet Triumph of Love, which are my starting point. I give the German first so people will have it, and in what follows I can just paraphrase and occasionally give quotes in English translation:

He begins by observing that In their "mis-en-page" - how the figures are put on the page - the figures are similar to a famous series of Sybils (p. 178):

A close parallel to the mis-en-page of the Triumphs are the copper engravings with depictions of the Sibyls, which were attributed to Baccio Baldini and Francesco Rosselli.

These were done in Florence of the 1470s, according to Wikipedia. An example might be Rosselli's Phrygian Sybil, which I put to the right of the Robertet below for comparison.

Whether Rosselli actually influenced Robertet depends on how common such a layout was already in France and whether Robertet's design was original with him, or something he copied. I don't know of anything Italian like this, combining verses and pictures, before the 1470s, but perhaps there is.

Ziegler adds that Robertet is emphasizing the psychomachia (soul-strife) aspect of Petrarch poems, each physically fighting and overcoming the one before, a tradition that of course has a long history, back to Prudentius in the fifth century. Ziegler cites Matthias Greuter in 1596 as another illustrator of Petrarchan Triumphs who emphasizes that aspect (at

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Petr ... s_triumphs#, Greuter is second from the bottom; it seems to me that there are several others on this webpage, all 16th century French or Flemish/Dutch, that share this emphasis). This is a tradition that also existed independently of Petrarch, for example in Francesco Barbarino's

Documenti d'amore, a work done by a Tuscan in exile in Provence (and so perhaps of influence in France) before 1348 (

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francesco_da_Barberino, or the Vatican Library's website).

Here Cupid does battle against a group of twelve virtues. There are also illustrations of the triumphs of love and fame, as Wikipedia identifies them.

Another possible source is tarot cards. Zeigler mentions Nicole Reynaud's proposal that the lack of chariots is due to the influence of tarot cards (p. 180, n. 573).

Nicole Reynaud hypothesized that the figure compositions could be inspired by tarot cards: EXHIBIT.-CAT.PARIS 1993, p. 354. The scheme represents a rare alternative to the main strand of the chariot procession representational tradition.

Of course, he also said earlier that this suggestion was "without evidence." But it seems to me that it would be surprising if a Gonzaga bride, granddaughter of Bianca Maria Visconti's friend Barbara of Brandenburg, did not take tarot cards with her to Moulins, and that the local writers would not have been interested (for the reference, see the second link to Huck in my previous post). They clearly did have the "Tarot of Mantegna" set of 50 hierarchically arranged images, which also doesn't use chariots (with the possible exception of Mars) - just compare 24461's pictures of Saturn (

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... f/f21.item), Jupiter (next image), Mercury (a few further), and Mars, with their "Mantegna" equivalents, or any of the Muses (folio 28r-36r of 24461 for them; the "Mantegna" at

http://www.levity.com/alchemy/mantegna.html). But what the tarot has that the "Mantegna" doesn't is, along with other subjects, cards similar to Petrarchan triumphs - Love, Time (the Old Man), and Death for sure, the rest probably: Eternity in the Judgment card, then called the Angel, and Fame in the Chariot; Chastity is found for sure only in the Visconti di Modrone Chariot card (because of the shield she holds), where (I think) Fame is represented by the World card (Nathaniel thinks it was another card with a chariot). Some of the other subjects correspond, too: the Wheel of Fortune, dukes and duchesses replacing the papals and imperials, proverbs and sayings instead of the virtues, and the Sybils for a Christian eschatological ending.

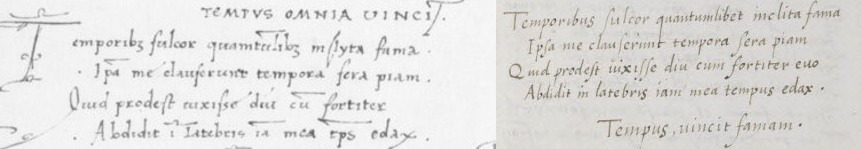

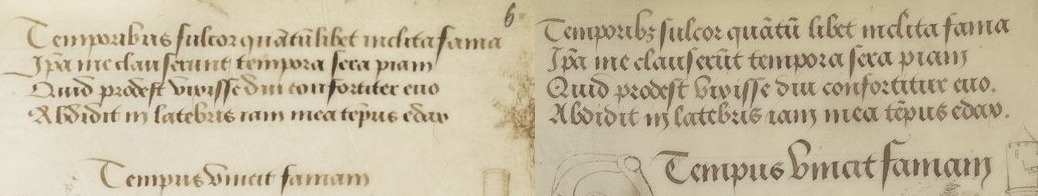

Ziegler also notes that around the same time a different representation schema was being used to illustrate the Triumphs in France.

Marie Jacob identifies with the miniature in the Codex Cod. Gall. 14 (Fol.1r) of the Bavarian State Library another French special solution from around 1450: JACOB 2005, esp. p. I96-I97.

He does not elaborate, and I cannot find that image on the Web, but Simona Cohen describes it (

Transformations of Time and Temporality, Appendix, p. 319):

The Triumph of Love seems to be a direct interpretation of the text by a French miniaturist who was unfamiliar with Italian illustrations of the Trionfi. Cupid and Venus are seated on a cart led by four horses, while the victims of Cupid’s arrows stand conversing in the foreground and the poet sits with a book on his knees. this is probably the oldest known illuminated copy of the Trionfi produced in France.

It is with a French translation of Petrarch's poems, although likely not the oldest copy of that translation (there is also, I discover elsewhere, the unillustrated BnF Fr. 1119, at

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... checontact).

For the rest, Ziegler is content to cite works that seem to have been influenced by the Robertet book. Such comparisons are worth exploring, to see what it was that later artists identified as important features. He mentions the stained glass window at Ervy-le-Chatel of 1502 (I discussed it at

viewtopic.php?p=26287#p26287, in connection with its Triumph of Death), for its consistently frontal presentation of the main figures, despite having the chariots that were missing from Robertet. I would add that in most of the scenes, figures representing the previous Triumph can be seen lying down beneath the chariot, the same motif as in Robertet. Below are the first three (

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File ... _76754.jpg).

In the image of Love, the figures aren't prostate, but a crowned figure seems about to be run over by the front wheel and an ecclesiastic plus others by the back. In the case of Death, as Trapp observed, the words Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos are even there, as in Robertet's illustration of that Triumph (they are just called "the sisters" in the verses). The verses under each image do not seem to be related specifically to those of Robertet, nor the precise ways in which Cupid, Chastity, and Death are portrayed. The naming of the three Fates could be following certain Italian manuscripts that did so (see my earlier post), but putting people under the wheels of any chariot but Death is first seen, at least as known, in Robertet. Likewise, the bit in Chastity's mouth was a conventional if rare attribute of Temperance (like the vessel pouring liquid; the bit is seen in Giotto's Temperance fresco, ca. 1305 Padua). However, Robertet's verses for Love also mention reins and a bit (I will quote them a little later).

Ziegler also mentions a fragment of a tapestry now in the Detroit Institute of Fine Arts. Google Books and archive.org have it in an exhibition catalog they scanned,

Masterpieces of Tapestry from the Fourteenth to the Sixteenth Century: An Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Issue 13, 1974, p. 150.

The verses are different from Robertet's, but still in the psychomachia tradition.

Ziegler also relates the Robertet to BnF ms. fr. 594 (

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... 6/f22.item, generally dated to 1502-3), making an observation I hadn't noticed: in small gold letters it identifies three of the people (far left) following the chariot as Jupiter, Neptune, and Pluto.

![Pétrarque_Les_Triomphes_traduction_rouennaise_[...]Petrarca_Francesco_btv1b60007856DET1.JPEG](./download/file.php?id=2967&sid=598e08dd949cf8c136ece2d51b008dac) Pétrarque_Les_Triomphes_traduction_rouennaise_[...]Petrarca_Francesco_btv1b60007856DET1.JPEG

Viewed 1802 times 59.03 KiB

Pétrarque_Les_Triomphes_traduction_rouennaise_[...]Petrarca_Francesco_btv1b60007856DET1.JPEG

Viewed 1802 times 59.03 KiB

The first two have obvious crowns. In the Robertet, all three have them, but Pluto's has fallen off. Similarly, in the tapestry fragment two crowned heads are visible below Cupid, on the far left and far right.

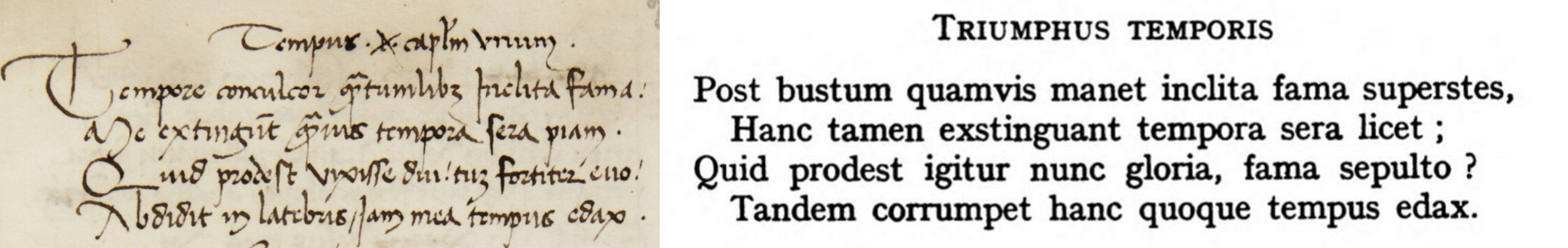

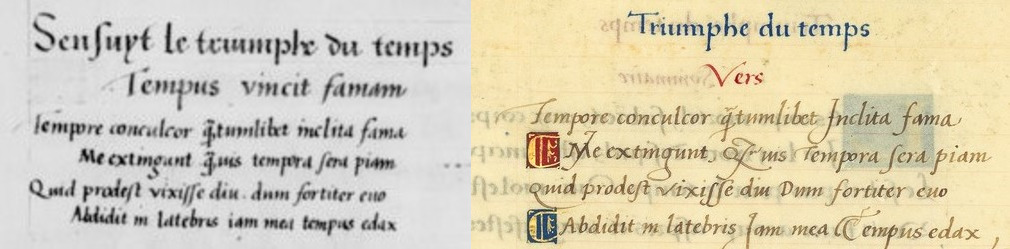

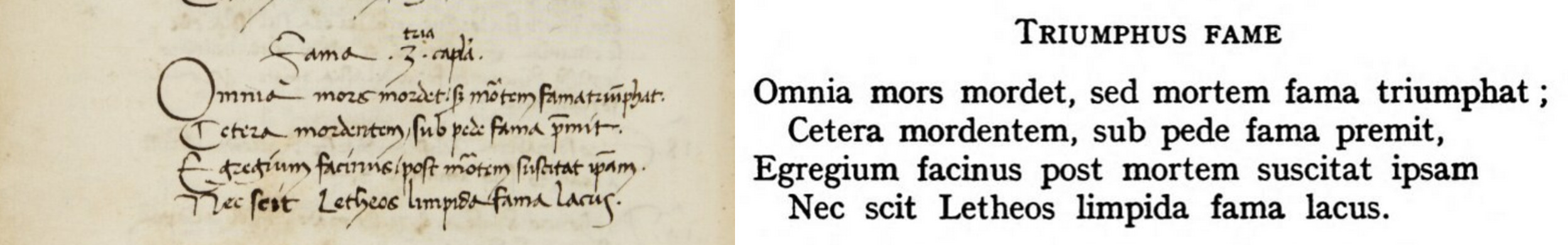

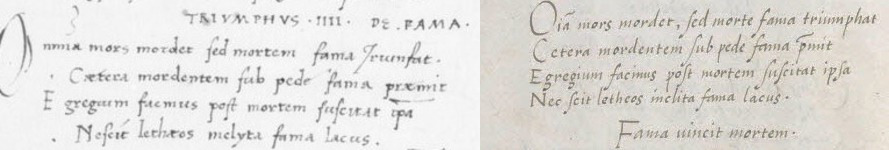

The identification of these three gods, each a "king" in his own realm, corresponds to Robertet, in both the verses and the image. I will repeat here, first the Latin, then the French, and finally my translation of both. (Ziegler pp. 177-178, followed by my machine-assisted translations):

Ecce Coronati telo stern nu(n)tur amoris.

Cum Iove nectunnus cu(m) Iove pluto subit.

Lora voluptati reges imponite . . .

His telis supero reges, mare, sidera, terras,

Plusque arcus noster quam lovis arma potest.

Cupido a de son dart prosternez

Jovis, neptunne et pluton couronnez,

Roys ensuivans folle amour et plaisance,

D’eulx triumphant nonobstant leur puissance . . .

Behold, the Crowned ones are laid low with the weapon of love.

With Jupiter, Neptune, with Jupiter Pluto submits.

Reins of pleasure are put on kings: . . .

These darts above kings, sea, stars [or sky], lands,

More our bow can do than Jove's weapons.

Cupid has with his dart prostrated

Crowned Jove, Neptune and Pluto,

Kings following mad love and pleasure,

On them triumphant despite their power. . . .

Ziegler says that Jupiter probably represents air, Neptune Water, and Pluto Earth, three of the elements. To me Jupiter's realm is a bit more inclusive, including the stars. In any case, the three together represent the World (of "Amor Vincit Mundum" - Love Conquers the World).

Ziegler appears unaware that the Latin quatrains (minus the "vincit" and the couplet) are also found in a manuscript in Modena, which is also its historical location as early as is known; Nathaniel brought it to our attention, noting that it has the year 1447 written on f. 105r (the quatrain is at

https://edl.cultura.gov.it/item/vmr9oevrwd, at f. 296r). But is the quatrain really so early, reflecting, by its "Behold," a now-lost visual presentation even earlier, singling out the three gods? Where in the Italian Petrarch illustrations at any time are these three singled out as particular victims of Cupid's arrows?

Jupiter was, yes. We can see that in a ca. 1480 ms. associated with the scribe Sanvito (now in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore).

That it is Jupiter is clear from the end of the first section of Petrarch's poem, where his guide tells him (

https://petrarch.petersadlon.com/read_t ... age=I-I.en):

"What shall I say? To put it briefly, then,

All Varro' s gods are here as prisoners,

And, burdened with innumerable bonds,

Before the chariot goes Jupiter."

Sanvito shows the chains.

Petrarch does mention Pluto and Persephone, as a couple and just in passing. He doesn't mention Neptune at all. It strikes me as odd that such a specific tradition, if it existed in pre-1447 Italy, would so uniformly die out. I don't even know of depictions of Cupid assailing Pluto and Neptune in other contexts, unlike, say, Apollo (with Daphne). It seems at least as likely that depicting the three gods was Robertet's initiative, expanding on Petrarch and an Italian tradition that showed Jupiter tied to the front of the chariot. It justifies the motto "Amor Vincit Mundum" that follows Robertet's quatrain. In that case, the same verses (which omitt the "Vincits") in the Modena ms. would be a later addition to what was there before (there are numerous blank pages at the end, interspersed with a few that use only a small part of the page and seem clearly to be addition. After being invented by Robertet in the 1470s, they would, on this hypothesis, been passed on by some Bourbon visitor to Ferrara, or in a letter, then recorded in a convenient Trionfi manuscript. Gilbert, Count de Montpensier, was there in 1485, according to the information Huck found back in 2010,

viewtopic.php?p=9118#p9118). But the couplet, which Robertet did not translate into French, was left out, along with the "vincit". Both help make the meaning clear, and with the couplet mentioning only Jupiter, but all three realms, he becomes a kind of three-in-one.

Ziegler discusses one more manuscript with Robertet-like images. From about 1540 and now in the Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin, Handschriftensammlung, [SMPK], it is their cod. phil. 1926. I cannot find this ms. online, but Ziegler offers the following description (p. 89, n. 266):

In the miniature of Cupid's triumph (fol. 2V) of the Codex SMPK cod. phil. 19266, only one of the defeated parties is identified as king, although the associated distich speaks of “roys” in the plural; Lecoq interpreted him as the wise King Solomon: LECOQ I988A, p. I40. The other two kings are replaced by Hercules and Samson - recognizable by their attributes. The powers defeated by Cupid are no longer the elements of the cosmos, but rather strength, virtue and wisdom.

I cannot find this ms. on the Web, but his descriptions of its Triumph illustrations correspond very much to those of the "Bildindex der Kunst und Architektur" at

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Petr ... 1-love.jpg), including a deviation from Robertet in the Triumph of Divinity (which Robertet and Petrarch called "Eternity": the Berlin ms. and Bildindex image have the Christian-imaged version). Interestingly, the ms. also has French paraphrases of the Latin quatrains. Ziegler (p. 90) suspects that someone at one time owned both this manuscript and BnF fr. 24461, because both were at times part of the library of Duke of La Valliere in the mid-18th century, and the two may have been passed down together.

Ziegler ends his commentary on this page of 22461 by saying (p. 180):

In France at the end of the 15th century, Marsilio Ficino's concept of Platonic love was intensively received and related to Christian-religiously inspired ideals of virtuous love, as was also the case in Symphonies Champier's Livre de vraye amour, part of the Nef des dames vertueuses (Lyon 1503).

What does Ficino's concept of Platonic love have to do with the concept of love illustrated by Robertet? Petrarch did not know about Platonic love as presented by Ficino, of course: he couldn't read Greek, and there is no evidence that anyone else translated the Phaedrus for him (he apparently did have a copy of Plato's works). But he did have the chivalric tradition, which was at least as big in France as in Italy in the later Middle Ages. In that tradition, love is ennobling as well as enslaving. For example, in part 2 of his Triumph of Love (

https://petrarch.petersadlon.com/read_t ... ge=I-II.en) he mentions a man who out of love gives his beloved the poison she desires, so as not to live as another's slave. Another man, out of paternal love, gives his young wife to his son, since both desire it. It is a feature of Love's bonds that they not only enflame but also constrain. Likewise in the chivalric tradition, love not only enflames the knight for his lady, but constrains him to live or die in her service without hope of consummation. It is much like the love that causes the charioteer in Plato's Phaedrus to bow down in awe and worship at the sight of the beloved, as an image of divine beauty seen in the heavens before birth.

Such a conception of love applied both in Robertet's France and in the courts of northern Italy. An Italian example that Ziegler cites elsewhere in his book is a medal made for Leonello d'Este in 1444, showing Cupid teaching a lion how to sing from what is written on a scroll. 1444 was the year of his second marriage. The lion is Leonello ("little lion"), and the medal expresses his submission to love. Here I would add that it also says that such submission is noble even if its expression appears awkward and foolish, as would be the case of a lion trying to sing.

In France we see this tradition even in the time of Charles VIII and Louis XiI, i.e. the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the next. A 1488 Venice print edition of Petrarch's Trionfi, Banco Rari 103 of the Biblioteca Nazionale of Florence, had a series of illustrations done afterwards (to be inserted into the book), commissioned by the uncle of the Venetian ambassador to France 1485-88 and again in 1498, according to a study by Alessandro Turbil, from which I get the illustration (

https://journals.openedition.org/studif ... 73?lang=en). That series' Triumph of Love had Jupiter tied to the front of Love's chariot (at left below).

There is a similar French illustration, in Bibliotheque Ste. Genevieve ms. 0965, p. 28, itself of 1681-1687 but said there by the author, the librarian at Ste.-Genevieve, to be a copy of an illustration from two centuries earlier (

https://portail.biblissima.fr/ark:/4309 ... 0fadbff2bc; to see the page, go to the link there for p. 28 and find the second image). Instead of Jupiter it shows King David at the front of the chariot playing his harp. According to Turbil, this is an allusion to Charles VIII, who fancied himself a latter-day David, or conceivably to Louis XII (machine translation of Turbil's French):

Charles VIII was successively David conqueror of the giant Goliath, for his first royal entry into Paris in 1484; the young shepherd anointed by God, upon entering Rouen in 1485; and again in Troyes in 1486, in order to prove that a child can, by divine will, become a triumphant king (29). This association at the level of the collective imagination will still work for King Louis XII, but to a lesser extent. From this perspective, it seems likely that this account of the historia salutis concerning David suggests to readers of this period a parallel with the biography of the child king; thus the illuminator's choice to substitute David in chains for Jupiter could not be random.

Associating French kings with David, as prisoner of Love, can hardly be meant pejoratively. David is merely a more accomplished version of Leonello's lion.

Devotion to ideals is less clear in the typical Florentine Petrarch illustration, in which Samson is shown submitting to Delilah's underhanded haircut, Aristotle to Phyllis's domineering use of him as she would a horse, and Cupid as a mischievous little boy shooting his arrows at people willy-nilly. But it is in the former spirit, of Love's arrows as ennobling, that Robertet in his verses says, after the part I quoted, that the ruler who practices moderation endures and the one who does not falls: moderation is constraint. Here is the remainder of the quatrain (plus the one line vincit) and huitaine (Ziegler 177-8):

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . septra

Immoderata ru(un)t et moderata durant

Amor vincit mu(n)du(m).

Princes, mettez frai(n) a voz voluptez

Car les ceptres qui sont immoderez

Tumbent tantost et ne sont point estables

Les moderez sont fermes et durables.

Amour vainc le mo(n)d.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .scepters

Uncontrolled rush and stay controlled.

Princes, apply the bit to [i.e. rein in] your voluptuousness,

For the scepters which are immoderate

Sometimes collapse and are not stable;

The moderate ones are firm and durable.

Love vanquishes the world.

Notice here the bit, which in the stained glass window is in the mouth of Chastity. However, it is not only love leading to abstinence that is ennobling, but any love in accord with virtue, love in moderation, as temperance was characterized, including here love of possessions. It is not that Cupid merely lays people low; he also ennobles, by creating the need for such restraint. On the other end of the spectrum, St. Sebastian's, too, can be seen as love-darts, enflaming the saint's passion and longing for God.

Such a love is also implied in the Tarot Love cards of this time. In the Modrone and Colleoni versions, the restraint is expressed in the handshake that seals the marriage contract, one of mutual obligations one to the other. It is also in the Modrone's Chariot card (

https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2002878,i image 50) where she holds her shield triumphantly and her horses are under control, even though one, as in Plato's allegory, is unruly and in need of restraint. In Italy, Plato's Phaedrus was topical in the 1430s and earlier, long before Ficino. That Plato presented all his ideals, gods, and even human souls as charioteers may be one reason why the Trionfi illustrations (as well as those of the "children of the planets" series) presented them similarly, an allusion to Plato for the humanistically inclined, even if to the masses they only suggested a procession.

In ca. 1500 card of Ferrara or Venice (fourth from left) and another from around the same time, probably reflecting a style of Florence or Bologna, even if the card itself might be from Perugia (see

http://pratesitranslations.blogspot.com ... rugia.html), it is the knight submitting to his lady and the lady accepting it, perhaps even keeping it on a lofty, chivalric plane - or, on another level, a marriage proposal.

In none of these except the Colleoni is Cupid presented in a way similar to how Robertet has him, upright posture, arrows held in the hand, pointing down, as if to throw them rather than shoot them from a bow. There also differences. On the card, Cupid seems to have two long shafts and no bow. Also, he is more the mischievous little boy than Robertet's proud youth. And of course nobody is being held down against their will. Nonetheless, Nathaniel has proposed that it could well reflect a ms. tradition that would have produced Robertet's images, back as far as pre-1447, because of the manuscript with the verses in Modena.

Except for that manuscript, there would be no reason to back anywhere near that far, it seems to me, at least based on the Robertet Triumph of Love. For one thing, it is known that copies of at least some of the Colleoni cards were made, because several such duplicates, more or less, have survived in various collections. They seem to have been done before 1500. If some were gifts, a copy of the card might have ended up in France. For another thing, there are known Petrarch

Trionfi manuscripts that have precisely the same pose as in the Robertet drawing. There is the one for Banco Rari 103 that I showed earlier, but it is not clear whether it would have gotten to France in time to influence Robertet. But there are two Ferrarese manuscripts that Nathaniel has drawn our attention to, made for Borso d'Este in 1459 and 1460: Dresden Mscr. Dresd. Ob. 26, image 5 (

https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/12986/5) and Vienna Cod. 2649, 4r (

https://onb.digital/search/635045). These dates are just before Jean Robertet is said, based on a letter that is part of a collection to which Jean Robertet contributed, to have been in Italy, the context suggesting to modern eyes 1462-3. It would have been easy enough to make mental notes and brief sketches, if he could get access to them. Or if not, then get them later, through family and diplomatic connections to Mantua and Ferrara. Here are their Triumphs of Love:

Here, oddly, we see a man in a papal tiara in front of the chariot. Is this a dig at the pope? Quite possibly. The reigning pope then was Pius II, who studiously avoided taking any position that required a vow of celibacy before he became pope, according to Wikipedia. Wikipedia quotes a book from the 1930s:

"The new Pope, Pius II, was expected to inaugurate an even more liberal and paganised era in the Vatican. He had led the dissipated life of a gentleman of the day and complained of the difficulty of practicing continency, a difficulty he did not surmount."

Well, perhaps it ennobled him anyway, if it was only a mistress.

What the person in the illustration is wearing is and was called a "triregnum," meaning reigning over three. Exactly what three the pope reigned over was not said. One suggestion on Wikipedia is that since the Emperor had three crowns - silver for Germany, iron for Italy, and gold for Emperor - the pope needed three as well. However, the man is bearded, at a time when popes were always clean-shaven. Jupiter, however, was presented as bearded (in the Sanvito and then for Banco Rari 103), and as king of the gods he would have ruled over Neptune and Pluto as well as his own domain of the air (if that is right) or Olympus. Hence the triregnum. If so, perhaps Robertet got the idea of three gods from the triregnum. I suppose the illustrations could have been reducing to one god an earlier tradition with all three gods. It seems to me more likely that the triregnum is there to indicate the pope, and the beard, implying Jupiter, is for purposes of deniability. I know of no tradition in which all three gods are subjected to Cupid.

Another discrepancy is that at least one of these two Ferrarese illustrations makes Cupid a little chubbier, younger, and less proud than the Robertet In the Sanvito that I showed earlier, we have both a bearded Jupiter and a proud youth. It is just a matter of mixing and matching. Moreover, it seems to me that the Sanvito was probably done in Mantua, where it or a copy could easily have reached Robertet. Sanvito had been born in Padua 1433 and trained there, perhaps, like Mantegna, with Squarcione. There is a nice piece on the internet by a person named Paul Shaw, summarizing a book on his life (

https://www.paulshawletterdesign.com/20 ... ce-scribe/). The critical part is this:

Sanvito was part of Cardinal Gonzaga’s household from 1463 until the Cardinal’s death in 1483. He moved to Rome in October 1464 and remained there, with frequent trips back to Padua, until 1501. During these decades he was the leading scribe of Humanist texts. Among his clients during these years were Sixtus IV, King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, Giovanni d’Aragona, Ludovico Agnelli of Mantova, and Bernardo Bembo (whose friendship dated to 1458). On many of these manuscripts he worked with the best miniaturists of the day, especially with Gaspare da Padova, another member of Cardinal Gonzaga’s household who he had met as early as 1462. The two began their collaboration in 1469 with a stunning copy of Julius Caesar and continued until the early 1490s when it is believed Gaspare died.

Although Gonzaga was from Mantua, he was based primarily in Rome. But it happens that he was not there at the time in question, ca. 1480. According to Wikipedia

From 1479 to 1480 Francesco hosted Angelo Poliziano at his court in Mantua, where the scholar poet wrote the Fabula of Orpheus (Italian: Fabula di Orfeo).

In these years, until December of 1480, the Cardinal was also in Bologna and Ferrara, Wikipedia adds, then in 1482 being assigned to Bologna. If his "court" was in Mantua, then probably Sanvito was, too, not only as part of that court but also because Mantegna was there, with all his connections. The ms. might even have made it to France in those years, as its history, before 1905 when it appeared on the London antiquities market, is quite unknown. It was in 1482, let us recall, that Chiara/Clara Gonzaga journeyed to the Robertets' vicinity.

In any case, it makes sense that between the later 1450s and the late 1480s there would have been numerous models for Cupid in Italy, easily accessible from Robertet's France. As to before then, the question remains open. On the one hand, there is the Modena ms. and the Colleoni card. On the other, the Modena manuscript specifies Jupiter, Neptune, and Pluto, never seen in either Triumph illustrations or tarot cards of Love, and there are extant but later models for Robertet's image. Or a version of the Colleoni card itself could have influenced Robertet. Or he was drawing on some version of Cupid that had nothing to do with Petrarch, such as that represented by the Barbarino illustration I showed near the beginning of this post and his Triumph of Love later in the book (

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... berino.jpg).