Oops—the Wheel of Fortune is obviously not in any Petrarchan illustrations. But you know what I mean.Nathaniel wrote: 14 Dec 2023, 09:52 The only other links between Robertet's images and tarot cards are the Love, Time, and Wheel of Fortune images, and none of those provide compelling evidence that the tarot deck was based on Petrarch's Trionfi. It could simply be that those three subjects were depicted on some tarot cards in the 1440s in a similar way to how they were depicted in some Petrarchan illustrations around that same time

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

182Thanks for the link, Ross. I couldn't seem to get anywhere navigating this library's website. There seems to be one other illustration besides that for Love, but I can't make out what it is supposed to be.

Nathaniel wrote,

Nathaniel wrote,

There are particular reasons why, reading Petrarch, one would come up with images found in the Visconti di Modrone: Chastity holding a shield (mentioned by Petrarch) and riding on a chariot (because of the distance Petrarch has her travel after her victory), and the Last Judgment as expressing Eternity (because it is the end of Time and mentioned as such by Petrarch). Likewise using the idea of an old man as Time (Petrarch's emphasis on decay). Also, it is natural, reading Petrarch, to see having all three of Temperance, Fortitude, and Chastity as a bit redundant, hence the disappearance of Chastity as a subject.

So does the nature of Robertet's design for Eternity, along with that of the Modrone's World card, show or suggest anything about Petrarch Trionfi illustrations before 1447? I hope that is the question you think is crucial. I certainly do see a few similarities between the images: they are both female, both hold two objects, one of them a crown, the other rather long at roughly the same height, and there is an arch or arc in the picture. As to what that shows, I need to study the question further. I was planning to discuss Robertet's Eternity last, after looking at the intervening four first, but I suppose I can jump the gun, as long as I am allowed to refer back to what I was going to talk about.

The general problem is, what can be attributed to invention and reasonable coincidence and what to inspiration from pre-existing models. It is reasonable to surmise that Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos were in Robertet's sources, because they are featured in previous Italian Petrarch manuscripts. They may even have been in Trionfi manuscripts before 1447, because 3943 might be that early. They are also in later ones. Robertet's use of them doesn't say anything about when the three Fates entered the tradition. Also, the French used them poetically quite independently as personifications of death; Robertet mentions Atropos in his "Complainct" of 1476, memorializing a fellow poet. But of course you are referring to an image, not a poetic device.

Robertet makes Eternity female. Well, "Eternite" in French is a feminine noun, just like "Fame" or "Renomme". "Amour" and "Temps" are masculine. "Mort" is feminine, hence the depiction of three women is ok, or a skeleton of indeterminate gender. In making Eternity's personification feminine, however, he is deviating from Italian tradition as we know it, which always has God the Father or Son. His deviation doesn't mean that there was an Italian tradition in which Eternity was given a feminine personification. He deviates from Italian tradition in several other ways: for example, he gives Fame the attributes of Prudence, including a mirror. Perhaps he was influenced by how Petrarch treated "good reputation" in De Remediis, in terms of vanity. A mirror sometimes does indicate vanity: an illustration by Hogarth to In Praise of Folly come to mind. Or perhaps, as Ziegler says, he saw Prudence as an essential ingredient of Fame. Artists can make innovations in existing patterns unless their client can be assumed to expect otherwise. Another example is the portable sun dial carried by Robertet's Time: I do not know of any such device on Time's belt otherwise (Ziegler calls it an astrolabe, but a sun dial is closer to what is shown, more clearly in 5066 than in 22461).

Then there is the crown instead of the usual globe held by the Father or the Son. Crowns are symbols of dominion, Ziegler says. So is the globe that the Father or Son holds in the usual depiction of Eternity. There is no need to stick to a globe if another symbol will do. In the case of Love, Robertet appears to have turned the pope or Jupiter into three gods, and for Time a purse into a sundial. At the same time, there happens to be a more specific source for Eternity's crown: the figure on top of Minchiate's World card holds one (below far right). Like Bologna's cards, Minchiate's have been remarkably stable over the centuries. The card likely already existed by the 1480s, as part of some common Tuscan deck. It may even have derived from a lost Trionfi illustration tradition originating with the Modrone World card.

Robertet would naturally assume that the World card was a representative of Eternity - even more than the Last Judgment, which is just the end of Time. In some versions of the World card, it may even have been identifiably feminine, as in the Charles VI card (above far left). If he had cards from Ferrara, he would assume that the World in Tuscany came after the card depicting the Last Judgment, as it did in Ferrara. Then it is natural to put a palm frond, for victory, instead of the arrow of the Minchiate card, or the staff on other cards, a symbol of authority. Robertet's figure holds them higher than other figures in his series hold their implements, because her victory is final. They are each at the same level as the other because that is how he depicted the two hands in preceding illustrations. The Sanvito also has God the Father's hands at that level, holding up the Cross. And Robertet puts a "rainbow" - Ziegler's word - instead of the world because he knows that Eternity in Petrarch series had such a thing sometimes.

Without more evidence, these things seem to me more likely than any unknown Italian Trionfi series, especially one going back before the Modrone. Despite the other similarities, Robertet's image is no more suggestive of a pre-1447 Trionfi illustration tradition than those cards are, because an illustrator is entitled to combine features from different sources and even make up a few.

Actually, I would go so far as to say that the tarot cards are one probable source for Robertet's Eternity, because of the way the personification holds the crown - as though to place it on someone's head, like the Father places a crown on the Son and the Father or Son on Mary. Also, Robertet's already has a crown on her head. It is the same on the two cards, the Modrone's and Minchiate's. In that way it is different from the orb held by God. It is not so much a symbol of sovereignty as of elevating someone else, in particular the chaste lover famous after death whose fame fades away, which is the fulfilling of the covenant symbolized by a rainbow.

However, I do not want to discount Nathaniel's hypothesis entirely. There are other parallels between later imagery and what is on the early Lombard luxury cards. There is the matter of the notches in Chastity's shield in the stained glass window and BnF fr. 594. Petrarch does not mention any notches, or that it is a jousting shield. A jousting shield would imply use of a lance, and no such weapon is mentioned either. It is only in the Modrone card that these notches are seen before those in France. Perhaps sketches or engravings corresponding to the cards were in circulation, or just verbal descriptions, either from Milan or from Savoy, which is where Filippo's widow returned after his death. More than one Savoy princess ended up in 15th century French court circles. BnF 594's Chastity, in one of the two, has two notches on the same side of the shield, as though a description specified two notches but failed to indicate that they were on opposite sides.

Such cards or descriptions may have survived in the seventeenth century. Both the Modrone and the Marseille II have just three people emerging from their graves in the Judgment card, the woman on one side looking at the central figure and the man on the other side looking up at the angel. Between the Modrone and the Marseille I, that pattern is lost, although Noblet might have known it but didn't follow it in an unambiguous way. The Cary Sheet pattern may have had some of this, as most of the six Petrarchans aren't there, all or in part. Enough of the Wheel is there to know that Robertet's is different. For the person on the ground, there was Ferrara's card. Mix and match. So I just say: more research and argumentation is needed.

Nathaniel wrote,

I think that ms. 24461 is significant for tarot history if there is a plausible case that its development was influenced by tarot cards. Otherwise, I don't know, but it is worth exploring, especially your hypothesis that it reflects Trionfi illustrations now lost and dating back to before 1447. In my post I was focusi about the Robertet illustrationThus, the link between the VdM World image and the Robertet Eternity image is essential here. If you reject it, then you reject any real significance of ms. 24461 for the history of tarot.

Nathaniel wrote,

I am not sure who you are arguing against. I don't remember proposing that the early tarot card images were influenced by Trionfi illustrations. I don't have an opinion on that. For me the relationship between tarot and Petrarch is mainly that six of the cards, however many there were at first, correspond to six of the subjects of Petrarch's cycle of poems. That does not seem to me a coincidence. Five of the subjects are in the Modrone and the sixth, Time, is in the other early Milanese cards, the Brera-Brambilla and the first artist Colleoni/PMB. The designers of the cards used various ideas and imagery that were current at the time, including imagery suggested by Petrarch. Also, the general concept of "trionfi" in the arts and society popularized by Petrarch applies naturally to a trick-taking card game and fits other subjects as well, based on the hierarchies of the time. Petrarch's poems, and the title of the whole sequence, fit that concept and suggest other cards along the same lines, such as imperials above kings, the virtues and the Wheel above them - the Wheel as another pre-existing conventional trumphator, if only from Boccaccio.The only other links between Robertet's images and tarot cards are the Love, Time, and Wheel of Fortune images, and none of those provide compelling evidence that the tarot deck was based on Petrarch's Trionfi. It could simply be that those three subjects were depicted on some tarot cards in the 1440s in a similar way to how they were depicted in some Petrarchan illustrations around that same time, without the former necessarily being an instance of the latter. All three were established allegorical subjects, which were depicted in many different contexts, not just the context of Petrarch's poem cycle (even if Time was a relatively rare one).

There are particular reasons why, reading Petrarch, one would come up with images found in the Visconti di Modrone: Chastity holding a shield (mentioned by Petrarch) and riding on a chariot (because of the distance Petrarch has her travel after her victory), and the Last Judgment as expressing Eternity (because it is the end of Time and mentioned as such by Petrarch). Likewise using the idea of an old man as Time (Petrarch's emphasis on decay). Also, it is natural, reading Petrarch, to see having all three of Temperance, Fortitude, and Chastity as a bit redundant, hence the disappearance of Chastity as a subject.

So does the nature of Robertet's design for Eternity, along with that of the Modrone's World card, show or suggest anything about Petrarch Trionfi illustrations before 1447? I hope that is the question you think is crucial. I certainly do see a few similarities between the images: they are both female, both hold two objects, one of them a crown, the other rather long at roughly the same height, and there is an arch or arc in the picture. As to what that shows, I need to study the question further. I was planning to discuss Robertet's Eternity last, after looking at the intervening four first, but I suppose I can jump the gun, as long as I am allowed to refer back to what I was going to talk about.

The general problem is, what can be attributed to invention and reasonable coincidence and what to inspiration from pre-existing models. It is reasonable to surmise that Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos were in Robertet's sources, because they are featured in previous Italian Petrarch manuscripts. They may even have been in Trionfi manuscripts before 1447, because 3943 might be that early. They are also in later ones. Robertet's use of them doesn't say anything about when the three Fates entered the tradition. Also, the French used them poetically quite independently as personifications of death; Robertet mentions Atropos in his "Complainct" of 1476, memorializing a fellow poet. But of course you are referring to an image, not a poetic device.

Robertet makes Eternity female. Well, "Eternite" in French is a feminine noun, just like "Fame" or "Renomme". "Amour" and "Temps" are masculine. "Mort" is feminine, hence the depiction of three women is ok, or a skeleton of indeterminate gender. In making Eternity's personification feminine, however, he is deviating from Italian tradition as we know it, which always has God the Father or Son. His deviation doesn't mean that there was an Italian tradition in which Eternity was given a feminine personification. He deviates from Italian tradition in several other ways: for example, he gives Fame the attributes of Prudence, including a mirror. Perhaps he was influenced by how Petrarch treated "good reputation" in De Remediis, in terms of vanity. A mirror sometimes does indicate vanity: an illustration by Hogarth to In Praise of Folly come to mind. Or perhaps, as Ziegler says, he saw Prudence as an essential ingredient of Fame. Artists can make innovations in existing patterns unless their client can be assumed to expect otherwise. Another example is the portable sun dial carried by Robertet's Time: I do not know of any such device on Time's belt otherwise (Ziegler calls it an astrolabe, but a sun dial is closer to what is shown, more clearly in 5066 than in 22461).

Then there is the crown instead of the usual globe held by the Father or the Son. Crowns are symbols of dominion, Ziegler says. So is the globe that the Father or Son holds in the usual depiction of Eternity. There is no need to stick to a globe if another symbol will do. In the case of Love, Robertet appears to have turned the pope or Jupiter into three gods, and for Time a purse into a sundial. At the same time, there happens to be a more specific source for Eternity's crown: the figure on top of Minchiate's World card holds one (below far right). Like Bologna's cards, Minchiate's have been remarkably stable over the centuries. The card likely already existed by the 1480s, as part of some common Tuscan deck. It may even have derived from a lost Trionfi illustration tradition originating with the Modrone World card.

Robertet would naturally assume that the World card was a representative of Eternity - even more than the Last Judgment, which is just the end of Time. In some versions of the World card, it may even have been identifiably feminine, as in the Charles VI card (above far left). If he had cards from Ferrara, he would assume that the World in Tuscany came after the card depicting the Last Judgment, as it did in Ferrara. Then it is natural to put a palm frond, for victory, instead of the arrow of the Minchiate card, or the staff on other cards, a symbol of authority. Robertet's figure holds them higher than other figures in his series hold their implements, because her victory is final. They are each at the same level as the other because that is how he depicted the two hands in preceding illustrations. The Sanvito also has God the Father's hands at that level, holding up the Cross. And Robertet puts a "rainbow" - Ziegler's word - instead of the world because he knows that Eternity in Petrarch series had such a thing sometimes.

Without more evidence, these things seem to me more likely than any unknown Italian Trionfi series, especially one going back before the Modrone. Despite the other similarities, Robertet's image is no more suggestive of a pre-1447 Trionfi illustration tradition than those cards are, because an illustrator is entitled to combine features from different sources and even make up a few.

Actually, I would go so far as to say that the tarot cards are one probable source for Robertet's Eternity, because of the way the personification holds the crown - as though to place it on someone's head, like the Father places a crown on the Son and the Father or Son on Mary. Also, Robertet's already has a crown on her head. It is the same on the two cards, the Modrone's and Minchiate's. In that way it is different from the orb held by God. It is not so much a symbol of sovereignty as of elevating someone else, in particular the chaste lover famous after death whose fame fades away, which is the fulfilling of the covenant symbolized by a rainbow.

However, I do not want to discount Nathaniel's hypothesis entirely. There are other parallels between later imagery and what is on the early Lombard luxury cards. There is the matter of the notches in Chastity's shield in the stained glass window and BnF fr. 594. Petrarch does not mention any notches, or that it is a jousting shield. A jousting shield would imply use of a lance, and no such weapon is mentioned either. It is only in the Modrone card that these notches are seen before those in France. Perhaps sketches or engravings corresponding to the cards were in circulation, or just verbal descriptions, either from Milan or from Savoy, which is where Filippo's widow returned after his death. More than one Savoy princess ended up in 15th century French court circles. BnF 594's Chastity, in one of the two, has two notches on the same side of the shield, as though a description specified two notches but failed to indicate that they were on opposite sides.

Such cards or descriptions may have survived in the seventeenth century. Both the Modrone and the Marseille II have just three people emerging from their graves in the Judgment card, the woman on one side looking at the central figure and the man on the other side looking up at the angel. Between the Modrone and the Marseille I, that pattern is lost, although Noblet might have known it but didn't follow it in an unambiguous way. The Cary Sheet pattern may have had some of this, as most of the six Petrarchans aren't there, all or in part. Enough of the Wheel is there to know that Robertet's is different. For the person on the ground, there was Ferrara's card. Mix and match. So I just say: more research and argumentation is needed.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

183Mike, we can be quite confident that Robertet was not responsible for designing those images, and that they must have been copied largely unchanged from a mid-15th century Italian source. The Latin quatrains not only refer directly to several elements visible in them, they also largely read as though they were intended as an explanation of them. By contrast, there is nothing in Robertet's additions to the text (neither his French translations nor the additional bits of Latin, which he can be presumed to have authored too) to suggest that he was responsible for adding any significant elements to the images at all.

The Eternity image provides one of the strongest arguments for this: the Latin mentions the palm frond, so that must have been there in the original mid-15th century Italian image. Robertet mentions the crown as well, but he does not appear to have added it to the image himself because if he did, you would expect him to allude in some way to its religious significance. The palm and crown were a typical representation of the reward of eternal life in heaven for Christians, especially Christian martyrs:

(The fact that the Latin quatrain also did not refer directly to the Christian's reward, and does not even mention the crown, is one of several reasons for thinking that the author of the Latin verses also may not have been responsible for designing the images, but was instead simply writing the verses to describe/explain/justify them after their creation by someone else. Moreover, by failing to highlight the Christian's reward, the Latin author is giving the figure's attributes an unconventional interpretation, just as with Chastity's attributes of palm and bouquet. There is good reason to think that the actual designer of the images would have viewed all these things in a more conventional way.)

UPDATED to correct my earlier error of mixing up the palm and the crown (as the attribute mentioned in the Latin verses)...

The Eternity image provides one of the strongest arguments for this: the Latin mentions the palm frond, so that must have been there in the original mid-15th century Italian image. Robertet mentions the crown as well, but he does not appear to have added it to the image himself because if he did, you would expect him to allude in some way to its religious significance. The palm and crown were a typical representation of the reward of eternal life in heaven for Christians, especially Christian martyrs:

I don't find it credible that Robertet would have felt the need to add the crown to go with the palm but at the same time would have written an accompanying French poem with no religious content whatsoever.Classical art used two symbols signifying victory, the palm branch and the crown of flowers or laurel leaves. In the 4th-century fresco above, the goddess Nike brings the two symbols to the winner of an athletic contest. The first picture on the right, also from the 4th century, adopts these symbols to represent Christian victory over sin and death. This adaptation of classical iconography was based on passages in Paul's epistles that compare the Christian life to a race for a prize or crown.

In medieval and later art the palm branch became the symbol of choice for identifying martyrs, as in the second picture at right. In images of the martyr's death it was often paired with a crown, carried to the dying saint by winged figures comparable to the Victory of classical iconography.

(source)

(The fact that the Latin quatrain also did not refer directly to the Christian's reward, and does not even mention the crown, is one of several reasons for thinking that the author of the Latin verses also may not have been responsible for designing the images, but was instead simply writing the verses to describe/explain/justify them after their creation by someone else. Moreover, by failing to highlight the Christian's reward, the Latin author is giving the figure's attributes an unconventional interpretation, just as with Chastity's attributes of palm and bouquet. There is good reason to think that the actual designer of the images would have viewed all these things in a more conventional way.)

UPDATED to correct my earlier error of mixing up the palm and the crown (as the attribute mentioned in the Latin verses)...

Last edited by Nathaniel on 16 Dec 2023, 17:01, edited 1 time in total.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

184A little addendum to my previous post:

Not only did Robertet make no mention of the Christian's reward in his French verses, he appears to have consciously removed the only (indirect) allusion to it in the Latin verses, by changing the final line from Felices animas regia nostra tenet to Celestem patriam regia nostra tenet.

Not only did Robertet make no mention of the Christian's reward in his French verses, he appears to have consciously removed the only (indirect) allusion to it in the Latin verses, by changing the final line from Felices animas regia nostra tenet to Celestem patriam regia nostra tenet.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

185Nathaniel wrote,

Nathaniel wrote,

I don't know Latin grammar, so you will have to correct any translation mistakes.

The Queen herself seated in triumph with the trophy

The old palm of slain Time I bear,

King Love and Shame, Death, Fame and Time I assail

Our kingdom holds the celestial country.

Eternity conquers all, overcomes all.

A crown may be implied by her being a queen, but that would be the one she is wearing, not holding.

In the French, a crown is mentioned:

from Time passed I bear palm and crown

Joyfully as victorious

Over glorious created things,

Worldly Love and Pudic Chastity,

Death, Fame and Time, however old and ancient:

Everything will end, but I have my mansion

Eternal in heaven in clear vision.

Eternity conquers all.

Is this crown one she is wearing or one she is holding? It is not clear (the French "porter" fits either); as if to cover his bases, the artist has her wearing one and holding another. As a result, it is not clear whether the verses are talking about a crown she is proffering or one she is wearing. In the first case, it would indicate that she is awarding someone victory. In the second, it would indicate her queenship. The 1490-1500 image suggests that the crown she is holding is being awarded to someone not in the frame. But that is not in the verses. I hadn't noticed that until you pointed it out, so thanks for that. I only disagree with what you make of it. Usually, what is shown in an Eternity scene, when it is one of the Petrarchan six, is God's dominion over everything. The verses replace God with pesonified Eternity, but it comes to the same thing. If the image showed her only wearing a crown and holding a palm frond, that would mean the same. But the second crown conveys, something more like what the Minchiate card conveys, or the Visconti di Modrone World card: salvation to heroes; and the palm frond then conveys the same thing. Anyway, I am quite lost as to what you think the mid-15th century image would have depicted, other than a lady and a crown.

Nathaniel wrote,

If the mid-15th century image had a crown in her hand, then yes, it would be surprising that the mid-15th century quatrain didn't mention it. Since it didn't, that's a good reason for assuming that the pre-1447 century image, if there was one, did not show her holding a crown, if the image was first and the quatrain later.

Actually, the salvation of heroes is a pagan theme as well as a Christian one. After Nike hands the palm and the wreath to the hero, she whisks him off to the Isles of the Blessed. In the 1490-1500 image, the only one I know, Eternity gets that role. That theme is acknowledged in the Latin couplet that follows the French:

Time, Fame, Death, Power, Love, all fled,

I command the eternal gods alone to live.

What the second crown does, also giving the palm branch a second meaning (beyond the personification's victory, as in Chastity's palm branch), is the elevation of the hero/martyr to the status that the divinities had in paganism: eternal life.

Nathaniel wrote,

Nathaniel wrote,

I do not see in the Latin verses for Chastity any suggestion that Chastity has a bouquet of flowers - so nothing in them that is unconventional. The flowers in the poem are associated with love. The bouquet is only in the image, where it indeed is quite unconventional. My guess is that the artist (either mid- or late 15th c.) saw the mention of flowers in the poem and may even have seen depictions of Cupid with flowers, such as Barbarino's in the 14th century. Another example is Gilles Corrozet, 1540, at https://www.emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/fren ... id=FCGa010.

Another example is Gilles Corrozet, 1540, at https://www.emblems.arts.gla.ac.uk/fren ... id=FCGa010.

Flowers are a customary lover's gift. So the artist probably thought that Chastity's taking his flowers could be another expression of her victory. I cannot account for the flowers any other way - in which case, the image would have been prompted by the poem, which can be Robertet's in the 1470s as much as anybody else's at an earlier time.

You refer to "the actual designer of the images" as someone with more conventional tastes. I assume by "actual designer" you mean the hypothetical designer in mid-15th century, as opposed to the actual designer of the images we see, from 1490-1500. So no flowers in the "actual" original? And no palms? Surely a palm branch held by Chastity is a perfectly conventional symbol for her victory over Cupid.

If the poems were written with the intent for them to be accompanied by an image, but one not yet realized by an artist, to guide the artist but not limit them, naturally he would not be the one to add anything significant to the images. In that case, they haven't been drawn yet. It is the artist who adds things so as to create an artistically pleasing scene, not the other way around. This is the normal procedure in manuscripts: first the scribe writes the text, leaving space for the image. Then the illuminator does the image. The writer of the verses may not even see it, although in this case he probably did. Also, the artist was not simply illustrating a text; he followed visual precedents in the subject-matter that were often not found in the particular text that went along with the image. The standard Florentine illuminations and cassone paintings on the theme of Petrarch's Trionfi are examples of that practice.The Latin quatrains not only refer directly to several elements visible in them, they also largely read as though they were intended as an explanation of them. By contrast, there is nothing in Robertet's additions to the text (neither his French translations nor the additional bits of Latin, which he can be presumed to have authored too) to suggest that he was responsible for adding any significant elements to the images at all.

Nathaniel wrote,

Where does the Latin mention a crown? Here is Robertet's quatrain, including the vincit after it:the Latin mentions the crown, so that must have been there in the original mid-15th century Italian image.

Perhaps by "the Latin" you mean the quatrain in the Modena manuscript. It doesn't mention a crown either.Ip(s)a triu(m)phali sedens regina tropheo

De vetere palma(m) tempore leta gero

Rex Amor atqu(e) pudor inors fama & tempus adibunt

Celeste(m) patria(m) regia n(ost)ra tenet

Eternitas o(mn)ia vincit

I don't know Latin grammar, so you will have to correct any translation mistakes.

The Queen herself seated in triumph with the trophy

The old palm of slain Time I bear,

King Love and Shame, Death, Fame and Time I assail

Our kingdom holds the celestial country.

Eternity conquers all, overcomes all.

A crown may be implied by her being a queen, but that would be the one she is wearing, not holding.

In the French, a crown is mentioned:

I am seated at the high triumphal throne;Je suis seant au hault triumphal throsne

Du temps passe porte palme et couronne

Joyeusement comme victorieuse

Sur les choses crees glorieuse

Mondaine amour et chastete pudicque

Mort fame et temps tant soit vieil & anticque

Tout prandra fin mais jay ma mention

Eterne au ciel en clere vision

Eternite vaint tout.

from Time passed I bear palm and crown

Joyfully as victorious

Over glorious created things,

Worldly Love and Pudic Chastity,

Death, Fame and Time, however old and ancient:

Everything will end, but I have my mansion

Eternal in heaven in clear vision.

Eternity conquers all.

Is this crown one she is wearing or one she is holding? It is not clear (the French "porter" fits either); as if to cover his bases, the artist has her wearing one and holding another. As a result, it is not clear whether the verses are talking about a crown she is proffering or one she is wearing. In the first case, it would indicate that she is awarding someone victory. In the second, it would indicate her queenship. The 1490-1500 image suggests that the crown she is holding is being awarded to someone not in the frame. But that is not in the verses. I hadn't noticed that until you pointed it out, so thanks for that. I only disagree with what you make of it. Usually, what is shown in an Eternity scene, when it is one of the Petrarchan six, is God's dominion over everything. The verses replace God with pesonified Eternity, but it comes to the same thing. If the image showed her only wearing a crown and holding a palm frond, that would mean the same. But the second crown conveys, something more like what the Minchiate card conveys, or the Visconti di Modrone World card: salvation to heroes; and the palm frond then conveys the same thing. Anyway, I am quite lost as to what you think the mid-15th century image would have depicted, other than a lady and a crown.

Nathaniel wrote,

I assume you mean adding a palm to the mid-15th century image which had only a crown. Otherwise I don't know what you are talking about. There is no crown in the Latin, unless one on her head is implied by calling her a queen. In the French, he adds mention of a crown, not the palm, probably meaning the crown on her head. The 1490-1500 image adds a crown in her hand to the one mentioned in the French, so that there are two. It seems to me that there is a Christian, or rather Judeo-Christian, religious content to the French and the Latin quatrain: not that of salvation, but simply of the victory of eternity over time: that time will end, unlike the unending time of the pagans.I don't find it credible that Robertet would have felt the need to add the palm to go with the crown but at the same time would have written an accompanying French poem with no religious content whatsoever.

If the mid-15th century image had a crown in her hand, then yes, it would be surprising that the mid-15th century quatrain didn't mention it. Since it didn't, that's a good reason for assuming that the pre-1447 century image, if there was one, did not show her holding a crown, if the image was first and the quatrain later.

Actually, the salvation of heroes is a pagan theme as well as a Christian one. After Nike hands the palm and the wreath to the hero, she whisks him off to the Isles of the Blessed. In the 1490-1500 image, the only one I know, Eternity gets that role. That theme is acknowledged in the Latin couplet that follows the French:

Please correct me if I have misunderstood:Tempora Fama Mors Virtus amor efugit omnis

Eternos iubeo vivere sola deos

Time, Fame, Death, Power, Love, all fled,

I command the eternal gods alone to live.

What the second crown does, also giving the palm branch a second meaning (beyond the personification's victory, as in Chastity's palm branch), is the elevation of the hero/martyr to the status that the divinities had in paganism: eternal life.

Nathaniel wrote,

Again I don't understand. It does mention the palm, as I've said. It is the crown it doesn't mention, or a second crown in the French. And that the author of the Latin verses may not have been responsible for designing the images is as true before the fact, for Jean Robertet, as for someone else after the fact.The fact that the Latin quatrain also did not refer directly to the Christian's reward, and does not even mention the palm, is one of several reasons for thinking that the author of the Latin verses also may not have been responsible for designing the images, but was instead simply writing the verses to describe/explain/justify them after their creation by someone else.

Nathaniel wrote,

I do not think the idea that time will end, or that Eternity rules heaven, is unconventional, which is what the Latin author is saying, no matter who it is. What the quatrain does not express, but is in the 1490-1500 image (because of the two crowns), is the idea that heroes will be rewarded with victory in eternity. That is in the holding of the second crown, as though to reward someone with it and the palm frond. That may be the 1490-1500 artist's addition, by a means that I think is suggested by certain tarot and Minchiate cards. I don't know any other images suggesting such symbolism that could reasonably have been known to the artist. There is the crowning of the Virgin, but that is something else.Moreover, by failing to highlight the Christian's reward, the Latin author is giving the figure's attributes an unconventional interpretation, just as with Chastity's attributes of palm and bouquet. There is good reason to think that the actual designer of the images would have viewed all these things in a more conventional way.)

I do not see in the Latin verses for Chastity any suggestion that Chastity has a bouquet of flowers - so nothing in them that is unconventional. The flowers in the poem are associated with love. The bouquet is only in the image, where it indeed is quite unconventional. My guess is that the artist (either mid- or late 15th c.) saw the mention of flowers in the poem and may even have seen depictions of Cupid with flowers, such as Barbarino's in the 14th century.

Flowers are a customary lover's gift. So the artist probably thought that Chastity's taking his flowers could be another expression of her victory. I cannot account for the flowers any other way - in which case, the image would have been prompted by the poem, which can be Robertet's in the 1470s as much as anybody else's at an earlier time.

You refer to "the actual designer of the images" as someone with more conventional tastes. I assume by "actual designer" you mean the hypothetical designer in mid-15th century, as opposed to the actual designer of the images we see, from 1490-1500. So no flowers in the "actual" original? And no palms? Surely a palm branch held by Chastity is a perfectly conventional symbol for her victory over Cupid.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

186Unfortunately, you didn't notice that I updated my post to correct the mistake I made with regard to the palm and crown in the original Latin (almost a day before you posted your reply to it).

But equally unfortunately, you haven't yet really grasped the religious significance of the palm and crown imagery. It simply would not have been possible for someone in the 15th century to look at that image with the palm and crown and fail to think of Christian martyrs and their heavenly reward. It is therefore not plausible that the creator of that image would have written a poem that fails to refer to this in any way.

Since you haven't been able to grasp that, it's not surprising that it also does not appear to have occurred to you that the crown on the Visconti di Modrone World card could likewise represent the Christian's reward of eternal life in heaven, even without the accompaniment of the palm. In the Middle Ages, there were images of martyrs and blessed souls showing only the crown without the palm. The webpage I linked to in my post above (the "source" link: you should definitely read that webpage if you have not already done so) links to an early example of such an image, in Ravenna.

Finally, do I really need to repeat myself again regarding the relationship of the Latin verses and the images?

The Latin verses read as though they were written to explain an existing set of images. They refer to a number of things that can be seen in those images, such as the palm frond and flowers held by Chastity, which are alluded to in the Latin verse mentioning Cyprus (an allusion to the palm) and the flowers on Mount Ida. The Latin verses appear to be motivated by a need to explain or justify images that would have seemed unusual for the time—they refer repeatedly to the calcatio layout of the figures, which we know would have been highly unusual for Trionfi imagery in the mid-15th century. The Latin verses also give some unconventional iconographic interpretations, such as the association of Chastity's palm and bouquet with Cyprus and Ida, rather than the more usual associations with victory over love and (in the case of the laurel bouquet) with the name of Petrarch's Laura. The Latin verses for Eternity contain a similarly unconventional view of the palm held by the Eternity figure, simply presenting it as a generic sign of victory (over Time in this instance), rather than associating it with the Christian's victory over sin and death. All these unconventional interpretations strengthen the impression that the verses were created to describe already-existing images that were created by someone else.

Robertet's French verses, for their part, simply follow the Latin ones with very little (intentional) alteration, and contain no suggestion that Robertet is likely to be responsible in any way for the iconographic content of the images. Since we know from the other pages of ms. Fr. 24461 that Robertet copied several other existing Italian images with little or no modification, it is logical to conclude that he has done the same with these six Trionfi images too.

But equally unfortunately, you haven't yet really grasped the religious significance of the palm and crown imagery. It simply would not have been possible for someone in the 15th century to look at that image with the palm and crown and fail to think of Christian martyrs and their heavenly reward. It is therefore not plausible that the creator of that image would have written a poem that fails to refer to this in any way.

Since you haven't been able to grasp that, it's not surprising that it also does not appear to have occurred to you that the crown on the Visconti di Modrone World card could likewise represent the Christian's reward of eternal life in heaven, even without the accompaniment of the palm. In the Middle Ages, there were images of martyrs and blessed souls showing only the crown without the palm. The webpage I linked to in my post above (the "source" link: you should definitely read that webpage if you have not already done so) links to an early example of such an image, in Ravenna.

Finally, do I really need to repeat myself again regarding the relationship of the Latin verses and the images?

The Latin verses read as though they were written to explain an existing set of images. They refer to a number of things that can be seen in those images, such as the palm frond and flowers held by Chastity, which are alluded to in the Latin verse mentioning Cyprus (an allusion to the palm) and the flowers on Mount Ida. The Latin verses appear to be motivated by a need to explain or justify images that would have seemed unusual for the time—they refer repeatedly to the calcatio layout of the figures, which we know would have been highly unusual for Trionfi imagery in the mid-15th century. The Latin verses also give some unconventional iconographic interpretations, such as the association of Chastity's palm and bouquet with Cyprus and Ida, rather than the more usual associations with victory over love and (in the case of the laurel bouquet) with the name of Petrarch's Laura. The Latin verses for Eternity contain a similarly unconventional view of the palm held by the Eternity figure, simply presenting it as a generic sign of victory (over Time in this instance), rather than associating it with the Christian's victory over sin and death. All these unconventional interpretations strengthen the impression that the verses were created to describe already-existing images that were created by someone else.

Robertet's French verses, for their part, simply follow the Latin ones with very little (intentional) alteration, and contain no suggestion that Robertet is likely to be responsible in any way for the iconographic content of the images. Since we know from the other pages of ms. Fr. 24461 that Robertet copied several other existing Italian images with little or no modification, it is logical to conclude that he has done the same with these six Trionfi images too.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

187mikeh wrote: 16 Dec 2023, 00:19 Robertet makes Eternity female. ...

Then there is the crown instead of the usual globe held by the Father or the Son. Crowns are symbols of dominion, Ziegler says. So is the globe that the Father or Son holds in the usual depiction of Eternity. There is no need to stick to a globe if another symbol will do. In the case of Love, Robertet appears to have turned the pope or Jupiter into three gods, and for Time a purse into a sundial. At the same time, there happens to be a more specific source for Eternity's crown: the figure on top of Minchiate's World card holds one (below far right). Like Bologna's cards, Minchiate's have been remarkably stable over the centuries. The card likely already existed by the 1480s, as part of some common Tuscan deck. It may even have derived from a lost Trionfi illustration tradition originating with the Modrone World card.WorldChVlMinchBolWorldWheel.jpg

Robertet would naturally assume that the World card was a representative of Eternity - even more than the Last Judgment, which is just the end of Time. In some versions of the World card, it may even have been identifiably feminine, as in the Charles VI card (above far left). If he had cards from Ferrara, he would assume that the World in Tuscany came after the card depicting the Last Judgment, as it did in Ferrara. Then it is natural to put a palm frond, for victory, instead of the arrow of the Minchiate card, or the staff on other cards, a symbol of authority. Robertet's figure holds them higher than other figures in his series hold their implements, because her victory is final. They are each at the same level as the other because that is how he depicted the two hands in preceding illustrations. The Sanvito also has God the Father's hands at that level, holding up the Cross. And Robertet puts a "rainbow" - Ziegler's word - instead of the world because he knows that Eternity in Petrarch series had such a thing sometimes.

Mike,

I think the emphasis here is more on dominion than eternity (although the Christian eternity is of course insinuated); the arrow is militant and has nothing to do with eternity in this specific card (perhaps the "love of Christ" to be spread with the Church Militant). The crown is over a world whose only named region is Europe. Put another way, the crown is over the dominion of Europe (just as I've argued the crown of the CY is over the Lombard vassal dowry of Cremona for Bianca/Sforza). The cosmic four winds seem to me to imply a dominance of Europe/Christianity over the whole earth. After the fall of Constantinople and further Turkish incursions, such crusade-related themes come to the fore. Finally, of the four exempli you posted, only the last is winged and adult (versus a putto), like a wrathful archangel.

Phaeded

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

188Phaeded: I am not clear about which crown you are talking about in the CY, as there are two of them - one in her hand and one above the scene. I am talking about the one in her hand. She seems to be offering it to someone, probably the knight below. I think the crown in the minchiate card is also being offered, as well as the orb in the Charles VI (and the Rosenwald, which seems to me its popular equivalent, with wings). It is different from the orb in the Bolognese World card, which symbolizes the holder's dominion, with wings on it and his hat to signify rising above the world of change below. I am not sure about the orb in the hand of the person on top of the Bolognese Wheel. It represents dominion in the world (not over it) and may also be held out as a temptation to the one climbing up. Orb and crown are similar.

I do not see any putti in the cards I showed. And I don't think wings are necessary, if a figure is standing above a world. Anyway, the Bolognese World card's figure does have wings, on his hat (and the Rosenwald, although I didn't show it, has angel's wings). I do not know if there is a world domination theme of the sort you propose for the minchiate card. I don't see it in any other World cards. But it is not important in the context I am concerned with. It is merely a source for an image.

I was writing in the context of the illustrator of the Robertet, taking further Ziegler's assumption that those images came after the poems, and in France, not Italy. From that perspective, the illustrator is looking for how to represent Eternity. The poem does not give very much - just the idea of a kingdom with Eternity as queen, bearing a palm branch, no mention of having a crown in her other hand (as opposed to on her head), although it is not excluded - the trophy seems to be the palm branch. There is also the "Eternos iubeo vivere sola deos" as the Latin motto - I command the eternal gods alone to live," I think.

If the illustrator had a copy of the minchiate deck, he would naturally identify with Eternity the card with a trumpet-blowing angel, accompanied by people below emerging from tombs (if not on the minchiate version, then that of Ferrara/Venice); and since the World was after the Angel in Ferrara and France, it most likely relates to Eternity, too. So a palm frond in one hand, for victory, and a crown in the other, which elevates to her court the soul she gives it to. He would see crown and orb as equivalent.

I presented this process as an alternative to Nathaniel's view that the Robertet picture must predate the poem, at least in its Modena version (which has a kingdom of happy souls rather than gods).

I am not disagreeing with you, Phaeded, about the symbolism of crowns as dominion. But I think there is more, at least the crown (or orb) in the hand, which suggests offering it to someone. That fits the "martyr" interpretation, but I think another is more appropriate: a symbol of victory and dominion over the world more generally. To the extent that death is part of this world, when the lady has a trumpet in the other hand (the CY), it is a symbol of the victory of Fame, and a kind of dominion after death. Worldly Fame, in time, is a similitude of eternal fame (the latter in Petrarch's Triumph of Eternity), and both a kind of deification, as in the euhemerist tradition of "deified heroes," which of course Filippo Maria Visconti knows all about. It seems to be alluded to in Robertet's Latin motto, too. The "happy souls" version tones it down.

I suspect that there was also a tradition in which receiving a crown from an angel just meant going to heaven, regardless of whether one is a martyr. I recall a modern American bluegrass/country music song in which the singer sings of getting a crown in the context of life after death, but with no suggestion of martyrdom. There is also the minchiate Hope card, which has a lady praying toward the top right, where there is a crown. It symbolizes God, but might also suggest that the crown could be hers.

Nathaniel: I guess we have to agree to disagree. I fail to see what martyrdom has to do with Petrarch's Triumph of Eternity, the Modrone World card (or any World card), or the verses on the Robertet page. Perhaps the illustration can be construed as the martyrdom of Love, Chastity, Death, Fame, and Time, which lie dead at Eternity's feet, but only in a comical and inappropriate way. They are not martyrs.

And if the palm on the Chastity page goes with Cyprus, like the flowers with Ida, the poem associates both with Venus, not Chastity. (I assume we agree about that.) The illustrator has merely used these mentions by the poet for inspiration - or vice versa. But it seems to me more likely the former, because I think a poet will be more careful about images than someone just turning out illustrations, using whatever models he has at hand.

In the Chastity illustration, the only one who has died is Love: but he is not a martyr in that illustration either. That the palm frond is featured in both illustrations tells me that its symbolism was conceived separately from its connection with a crown. The usual meaning is victory.

I want to resume my examination of Ziegler and the sources of the imagery, following his assumption that the poems came first, but cognizant of the other alternative. I turn to Chastity.

The main source for Chastity's palm frond would seem to be the standard Italian Triumphs of Chastity illustrations, as Ziegler observes, symbolizing "victory and virtue". The flowers, he also observes, come from the poem, expressing a kind of idyll. In that case it could be the other way around, too. I would add as a possible source the bouquet on illustrations of the Triumph of Love unconnected with Petrarch, expressing there a love idyll but now expropriated by Chastity.

So there is no connection to tarot cards in Robertet's image of Chastity. The only comparison might be to figures holding out things in both hands. But this is too generic, with too many other possible inspirations.

Ziegler notes that the palm frond is also part of the triumph of Chastity in the stained glass window series, where instead of the flowers she holds a pillar - indicative of her steadfastedness against Cupid in Petrarch's poem.

Pillars are a frequent attribute of Fortitude in tarot cards, e.g. in Bologna, Florence, and the Rosenwald, and also in the "Tarot of Mantegna," which is a clear influence in other parts of the manuscript. They could be an influence on the stained glass version and other French illustrations with that motif. Ziegler indicates one, Gilles Corrozet's Hecatongraphie, 1540, but pillars are also frequent in 16th century French illustrations of this Triumph. I have not investigated whether pillars represented fortitude earlier in France. I see no reason to assume that they didn't.

To be continued (with Death, Fame, and Time).

I do not see any putti in the cards I showed. And I don't think wings are necessary, if a figure is standing above a world. Anyway, the Bolognese World card's figure does have wings, on his hat (and the Rosenwald, although I didn't show it, has angel's wings). I do not know if there is a world domination theme of the sort you propose for the minchiate card. I don't see it in any other World cards. But it is not important in the context I am concerned with. It is merely a source for an image.

I was writing in the context of the illustrator of the Robertet, taking further Ziegler's assumption that those images came after the poems, and in France, not Italy. From that perspective, the illustrator is looking for how to represent Eternity. The poem does not give very much - just the idea of a kingdom with Eternity as queen, bearing a palm branch, no mention of having a crown in her other hand (as opposed to on her head), although it is not excluded - the trophy seems to be the palm branch. There is also the "Eternos iubeo vivere sola deos" as the Latin motto - I command the eternal gods alone to live," I think.

If the illustrator had a copy of the minchiate deck, he would naturally identify with Eternity the card with a trumpet-blowing angel, accompanied by people below emerging from tombs (if not on the minchiate version, then that of Ferrara/Venice); and since the World was after the Angel in Ferrara and France, it most likely relates to Eternity, too. So a palm frond in one hand, for victory, and a crown in the other, which elevates to her court the soul she gives it to. He would see crown and orb as equivalent.

I presented this process as an alternative to Nathaniel's view that the Robertet picture must predate the poem, at least in its Modena version (which has a kingdom of happy souls rather than gods).

I am not disagreeing with you, Phaeded, about the symbolism of crowns as dominion. But I think there is more, at least the crown (or orb) in the hand, which suggests offering it to someone. That fits the "martyr" interpretation, but I think another is more appropriate: a symbol of victory and dominion over the world more generally. To the extent that death is part of this world, when the lady has a trumpet in the other hand (the CY), it is a symbol of the victory of Fame, and a kind of dominion after death. Worldly Fame, in time, is a similitude of eternal fame (the latter in Petrarch's Triumph of Eternity), and both a kind of deification, as in the euhemerist tradition of "deified heroes," which of course Filippo Maria Visconti knows all about. It seems to be alluded to in Robertet's Latin motto, too. The "happy souls" version tones it down.

I suspect that there was also a tradition in which receiving a crown from an angel just meant going to heaven, regardless of whether one is a martyr. I recall a modern American bluegrass/country music song in which the singer sings of getting a crown in the context of life after death, but with no suggestion of martyrdom. There is also the minchiate Hope card, which has a lady praying toward the top right, where there is a crown. It symbolizes God, but might also suggest that the crown could be hers.

Nathaniel: I guess we have to agree to disagree. I fail to see what martyrdom has to do with Petrarch's Triumph of Eternity, the Modrone World card (or any World card), or the verses on the Robertet page. Perhaps the illustration can be construed as the martyrdom of Love, Chastity, Death, Fame, and Time, which lie dead at Eternity's feet, but only in a comical and inappropriate way. They are not martyrs.

And if the palm on the Chastity page goes with Cyprus, like the flowers with Ida, the poem associates both with Venus, not Chastity. (I assume we agree about that.) The illustrator has merely used these mentions by the poet for inspiration - or vice versa. But it seems to me more likely the former, because I think a poet will be more careful about images than someone just turning out illustrations, using whatever models he has at hand.

In the Chastity illustration, the only one who has died is Love: but he is not a martyr in that illustration either. That the palm frond is featured in both illustrations tells me that its symbolism was conceived separately from its connection with a crown. The usual meaning is victory.

I want to resume my examination of Ziegler and the sources of the imagery, following his assumption that the poems came first, but cognizant of the other alternative. I turn to Chastity.

The main source for Chastity's palm frond would seem to be the standard Italian Triumphs of Chastity illustrations, as Ziegler observes, symbolizing "victory and virtue". The flowers, he also observes, come from the poem, expressing a kind of idyll. In that case it could be the other way around, too. I would add as a possible source the bouquet on illustrations of the Triumph of Love unconnected with Petrarch, expressing there a love idyll but now expropriated by Chastity.

So there is no connection to tarot cards in Robertet's image of Chastity. The only comparison might be to figures holding out things in both hands. But this is too generic, with too many other possible inspirations.

Ziegler notes that the palm frond is also part of the triumph of Chastity in the stained glass window series, where instead of the flowers she holds a pillar - indicative of her steadfastedness against Cupid in Petrarch's poem.

Pillars are a frequent attribute of Fortitude in tarot cards, e.g. in Bologna, Florence, and the Rosenwald, and also in the "Tarot of Mantegna," which is a clear influence in other parts of the manuscript. They could be an influence on the stained glass version and other French illustrations with that motif. Ziegler indicates one, Gilles Corrozet's Hecatongraphie, 1540, but pillars are also frequent in 16th century French illustrations of this Triumph. I have not investigated whether pillars represented fortitude earlier in France. I see no reason to assume that they didn't.

To be continued (with Death, Fame, and Time).

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

189In this post I am going over again Death and Fame. Below are the Robertet illustrations (I have deleted the poems above and below) Regarding the Robertet illustrator's presentation of Death as the three Fates rather than the usual skeleton, Ziegler comments that this motif is inspired by Robertet's verses, as they are not mentioned by Petrarch. (Of course, as Nathaniel says, it could have been the other way around.) Ziegler cites Trapp in observing that the three Fates had been secondary characters in early Petrarch manuscripts (as has already been seen in this thread, viewtopic.php?f=11&t=906&p=26287&hilit=Naples#p26287). And he observes that in the V&A tapestries these continue, probably as a result of the same verses and the illustrations that accompany them. He notes how the one V&A tapestry is especially close to the Robertet illustration, apparently assuming that the influence was from Robertet to the tapestry and not the other way around. He does not attempt to date the tapestry (which others have dated to 1490). Here is Ziegler's German:

The connection to Lombard Petrarch ms. vat.barb. 3943 seems to suggest a tradition in which the Fates take on the role of Death trampling on Chastity before 1443. However, it remains possible that this one, from Lombardy, or the one from Naples (here again, see my post at viewtopic.php?f=11&t=906&p=26287&hilit=Naples#p26287), were copied and received in France. And Atropos at least, the Fate who cuts the thread, seems to have been a symbol of Death in French poetry, mentioned by Robertet in his Complainct.

Regarding the Robertet illustrator's presentation of Death as the three Fates rather than the usual skeleton, Ziegler comments that this motif is inspired by Robertet's verses, as they are not mentioned by Petrarch. (Of course, as Nathaniel says, it could have been the other way around.) Ziegler cites Trapp in observing that the three Fates had been secondary characters in early Petrarch manuscripts (as has already been seen in this thread, viewtopic.php?f=11&t=906&p=26287&hilit=Naples#p26287). And he observes that in the V&A tapestries these continue, probably as a result of the same verses and the illustrations that accompany them. He notes how the one V&A tapestry is especially close to the Robertet illustration, apparently assuming that the influence was from Robertet to the tapestry and not the other way around. He does not attempt to date the tapestry (which others have dated to 1490). Here is Ziegler's German:

The connection to Lombard Petrarch ms. vat.barb. 3943 seems to suggest a tradition in which the Fates take on the role of Death trampling on Chastity before 1443. However, it remains possible that this one, from Lombardy, or the one from Naples (here again, see my post at viewtopic.php?f=11&t=906&p=26287&hilit=Naples#p26287), were copied and received in France. And Atropos at least, the Fate who cuts the thread, seems to have been a symbol of Death in French poetry, mentioned by Robertet in his Complainct.

Since no tarot cards display the least tendency to show the three Fates, or even of Chastity/Laura lying prone as Death's victim (although showing the bodies of the powerful), the influence of tarot cards on the verses is unlikely.

For Fame, Robertet's illustrator has made the surprising move to give the personification attributes not otherwise associated with her, namely a looking-glass and a book, which, Ziegler notes, are attributes of Prudence in Giotto's depiction of that virtue in the Scrovegni Chapel. He continues:

That practical wisdom is a prerequisite for fame, however, is something else: many of the heroic exemplars of Fame are not known for their prudence. Ziegler gives no precedent for this last dictum, as though it were the illustrator's initiative, or that of some editor after the compositions of the verses. But Francois Robertet's verses (if he was the editor) also have no such message.

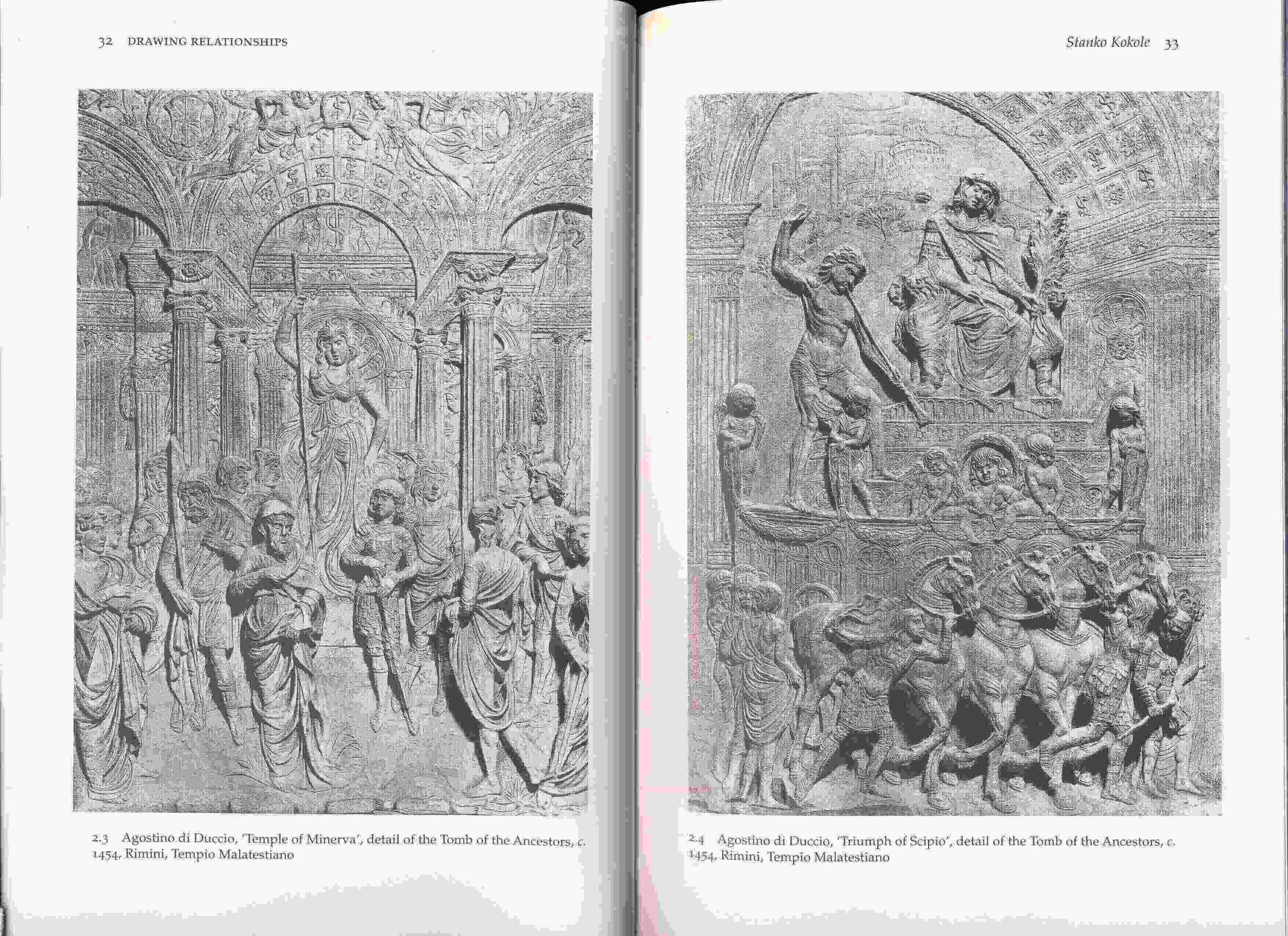

One possible source, I would add, is a "Temple of Minerva" relief in the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, done in the 1450s. It shows Minerva above a mixture of warriors and philosophers. The lower groups are as in Petrarch, but not the goddess above. It is there with another relief, a Triumph of Scipio. I include both below for your inspection. In the right hand photo, I am not sure which of the figures is Scipio, the one with the palm branch and scepter, or the lower figure flanked by putti. The relief of Minerva seems to be a variation on a "Temple of Fame" poem composed in ca. 1450 for Sigismondo Malatesta, mostly celebrating his military triumphs, but in the relief, Minerva substitutes for Fama (see Stanko Kokole, "The Tomb of the Ancestors in the Tempio Malatestiano and the Temple of Fame in the poetry of Basinio da Parma," in Charles Dempsey, ed., Drawing Relationships in Northern Italian Renaissance Art, 2004). Given that this is a product of the same milieu as the early tarot (Sigismondo as an early customer), we may wonder if perhaps Wisdom or Prudence was already associated with Fama in some early Triumph of Fame tradition.

The relief of Minerva seems to be a variation on a "Temple of Fame" poem composed in ca. 1450 for Sigismondo Malatesta, mostly celebrating his military triumphs, but in the relief, Minerva substitutes for Fama (see Stanko Kokole, "The Tomb of the Ancestors in the Tempio Malatestiano and the Temple of Fame in the poetry of Basinio da Parma," in Charles Dempsey, ed., Drawing Relationships in Northern Italian Renaissance Art, 2004). Given that this is a product of the same milieu as the early tarot (Sigismondo as an early customer), we may wonder if perhaps Wisdom or Prudence was already associated with Fama in some early Triumph of Fame tradition.

If this relief was among the models in the copy-books consulted by the designer/illustrator of the Robertet, it would be a satisfactory precedent for the attributes of Fame here. But he would also have to know that what was portrayed was Minerva and not Fama - and that is no easy task, unless the person bringing back the copy took care to note somewhere that it was Minerva. (Why Kokole made that interpretation escapes me, although it seemed convincing when I read it.)

Prudence with a mirror was ubiquitous. So was Prudence with a book. I don't know about their combination, but if Giotto did so, that is enough, given the chapel's fame. Another indication of Giotto's possible influence on Triumph depictions is the bit in the mouth of the stained glass version of Chastity, with reins on either side: Giotto's Temperance has such a bit and reins.

As with Death, the result is ambiguous, at least as to when this image of Fame with the attributes of Prudence would have been conceived. The Robertet image may have been influenced by the "Temple of Minerva," or vice versa. Given the relative obscurity of the relief, the notoriety of its sponsor, and fact whether an artist would even know it was Wisdom rather than Fame, it seems to me to count as evidence, although certainly not proof, that the image in Robertet is pre-1450. It could also be a sui generis novelty on the part of the artist or editor, or part of a tradition of which I am unaware.

But both Death and Fame show aspects that do relate to early illustrations of those subjects that may have existed in northern Italy before 1450, even if neither example of the Triumph of Death (Lombardy, Naples) puts the Fates in place of the usual skeletal figure. There is no suggestion that the imagery of any tarot card would have influenced the Robertet drawings.

Since no tarot cards display the least tendency to show the three Fates, or even of Chastity/Laura lying prone as Death's victim (although showing the bodies of the powerful), the influence of tarot cards on the verses is unlikely.

For Fame, Robertet's illustrator has made the surprising move to give the personification attributes not otherwise associated with her, namely a looking-glass and a book, which, Ziegler notes, are attributes of Prudence in Giotto's depiction of that virtue in the Scrovegni Chapel. He continues:

Here is the German: It is not necessary to cite an obscure Florentine merchant. The dictum that Prudence is "practical wisdom" was already a commonplace derived from Aquinas's teachings about Prudence in the Summa Theologiae, II-II-47-2, at https://www.newadvent.org/summa/3047.htm.Paolo da Certaldo, a Florentine merchant of the I4. Century, recognized Giotto's personification in the Scrovegni Chapel as that of "practical wisdom."596 Mirrors and books remained common in the 16th century as attributes of Sapientia. A well-known example of the Sapientia with a mirror is a woodcut illustration with Fortuna and Sapientia from Carolus Borvillus' Liber de Sapiente (I5I0/11). 597

Neither Jean Robertet nor Petrarch emphasizes a specific virtue in the triumph of fame, but they know virtus, virtue in general, as the decisive character trait of the famous. Already in Petrarch, among them are not only the warriors, but also the scholars, philosophers, poets, historians: "Pon' mente a l'alto lato, / che s'acquista ben pregio altro che d'arme." 598 With the fusion of Fama and Sapientia, the drawing makes an evaluation in this sense: practical wisdom, sapience, is the prerequisite for virtue and fame. 599.

That practical wisdom is a prerequisite for fame, however, is something else: many of the heroic exemplars of Fame are not known for their prudence. Ziegler gives no precedent for this last dictum, as though it were the illustrator's initiative, or that of some editor after the compositions of the verses. But Francois Robertet's verses (if he was the editor) also have no such message.

One possible source, I would add, is a "Temple of Minerva" relief in the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, done in the 1450s. It shows Minerva above a mixture of warriors and philosophers. The lower groups are as in Petrarch, but not the goddess above. It is there with another relief, a Triumph of Scipio. I include both below for your inspection. In the right hand photo, I am not sure which of the figures is Scipio, the one with the palm branch and scepter, or the lower figure flanked by putti.

If this relief was among the models in the copy-books consulted by the designer/illustrator of the Robertet, it would be a satisfactory precedent for the attributes of Fame here. But he would also have to know that what was portrayed was Minerva and not Fama - and that is no easy task, unless the person bringing back the copy took care to note somewhere that it was Minerva. (Why Kokole made that interpretation escapes me, although it seemed convincing when I read it.)

Prudence with a mirror was ubiquitous. So was Prudence with a book. I don't know about their combination, but if Giotto did so, that is enough, given the chapel's fame. Another indication of Giotto's possible influence on Triumph depictions is the bit in the mouth of the stained glass version of Chastity, with reins on either side: Giotto's Temperance has such a bit and reins.

As with Death, the result is ambiguous, at least as to when this image of Fame with the attributes of Prudence would have been conceived. The Robertet image may have been influenced by the "Temple of Minerva," or vice versa. Given the relative obscurity of the relief, the notoriety of its sponsor, and fact whether an artist would even know it was Wisdom rather than Fame, it seems to me to count as evidence, although certainly not proof, that the image in Robertet is pre-1450. It could also be a sui generis novelty on the part of the artist or editor, or part of a tradition of which I am unaware.

But both Death and Fame show aspects that do relate to early illustrations of those subjects that may have existed in northern Italy before 1450, even if neither example of the Triumph of Death (Lombardy, Naples) puts the Fates in place of the usual skeletal figure. There is no suggestion that the imagery of any tarot card would have influenced the Robertet drawings.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

190This is partly because you misunderstood what I meant in relation to the Visconti di Modrone World card. I was trying to get you to finally see what Michael Hurst pointed out many years ago, namely that the crown on that card could represent the "crown of life", the heavenly prize of eternal life won by good Christians: see James 1:12 (where the original Greek word for the crown, στέφανον, specifically means the crown bestowed on the winner of a race or game), 1 John 2:25, 1 Corinthians 9:24-25, Philippians 3:14, etc. This applies to anyone who goes to heaven, not just martyrs. And in early Christian art, the crown together with the palm sometimes signified the reward given to all faithful Christians, and not only signified martyrdom.I fail to see what martyrdom has to do with Petrarch's Triumph of Eternity, the Modrone World card (or any World card), or the verses on the Robertet page.

But by the end of the Middle Ages, the palm in particular had become quite a strong symbol of martyrs specifically—they were very often depicted holding it—so by the 15th century, the palm and crown together would have inevitably called martyrdom to mind.

And you are right: this association with martyrdom seems incongruous in the Robertet Eternity image. But it is not a good response to that puzzling fact to simply try to ignore the historical evidence and thereby dismiss the existence of the puzzle. A better response is to try to solve the puzzle—to ask the question, why did the artist put those details in this image even though they were incongruous? Why did the artist think this was a good choice?

The hypothesis I propose is that, in an earlier image on which this Eternity image (or a predecessor of it) was modeled, the crown and palm were preceded by a crown and a winged trumpet. A later artist, confronted with this, could not make sense of the winged trumpet in an allegory of Eternity, as it was so strongly associated with allegories of Fame, Glory, and Victory. So that artist decided to replace it with something that seemed like a more natural counterpart for the crown in this context, namely the palm, as it was well known that the combination of palm and crown signified the reward of eternal life in heaven. The artist might have been somewhat troubled by the strong association of these two objects with martyrdom, because martyrdom wasn't really relevant to this set of images. But the artist could have concluded that the palm was nevertheless still preferable to the winged trumpet, because at least it made some kind of sense in the context of Eternity, whereas the winged trumpet did not seem to make sense to the artist at all. In other words, it was an improvement in the artist's eyes, and so the change was made.

One might ask why the artist did not simply take away the trumpet and leave that hand empty; that would certainly have been an option. But the artist might have felt the need to place something in that hand in order to keep as close as possible to the model image, or might have felt that an empty hand was even worse than one holding a completely inappropriate object; and the iconographic pairing of palm and crown, being so well established, may have seemed irresistible.