Huck: your description of the Michelino is clear, concise and also goes beyond what I have seen before on the Web. I see that you are attempting to say what aspects of the various gods are important and to connect the cards with one another. You also have one eye on the CY, which I like, i.e. "Fame" and the 4 virtues.

But I would make different connections between cards. To me, the suits are two pairs of complementary opposites. The Middle Ages and Renaissance were fascinated by such double pairs. There was dry vs. wet and hot vs. cold. Their four combinations of two produce the four elements and the four humors. They, too, are sets of opposites. Fire (hot, dry) vs. water (cold, wet) and Air (hot, wet) vs. earth (cold, dry); as well as choleric vs. phlegmatic and sanguine vs. melancholic.

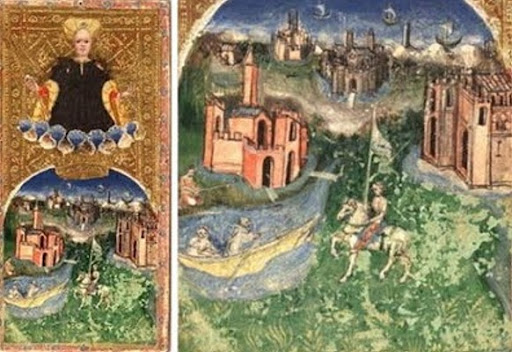

So in the Michelino, we have groups of four. The four elements may be seen in the suit of Riches: earth (Juno), water (Neptune), fire, and air (Aeolis, god of winds). The number four is also featured in the list of virtues, the four Platonic ones; thus we find them in the “virtues” suit, as you observe.

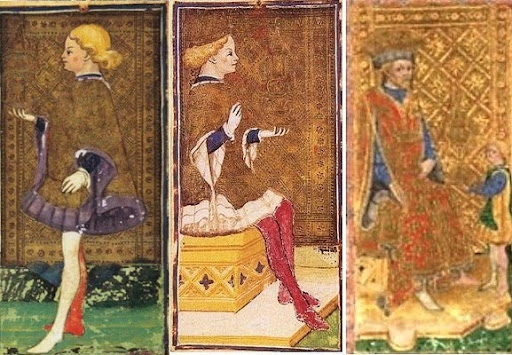

I would go further. Not only do we have groups of four, but four groups of four. two opposing pairs. In the suits, high-flying eagles are air (noble principles), phoenices are fire and metallurgy (e.g. smelting and shaping, into jewelry, coins, weapons, etc.), doves are water (baptism, Noah's scout, Venus’s foam), and turtledoves are earth (melancholy, solid steadfastness in the face of everything); turtledoves were emblems of faithfulness. Here it the eagles and the doves that are opposites, virtue vs. pleasure; and the phoenices and the turtledoves, volatility vs. fixedness, corrupting riches vs. incorruptible virginity, i.e. purity and independence. The trick is to have both pairs in balance, not excluding any.

We see the same pattern of double pairs in the Boiardo: fear vs. hope, and jealousy (i.e. hate) vs. love. And in later traditional play, the warlike Swords and Batons are less beneficial the higher the numbers, while it is the opposite for the peaceloving Cups and Coins.

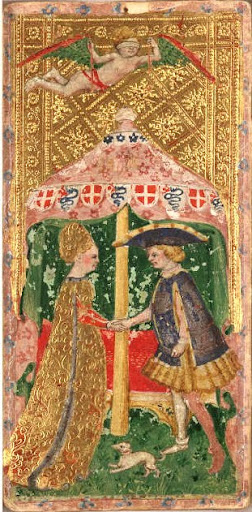

In this framework of opposing qualities, let us see how the gods contend. Jupiter is Justice, but the charms of Venus--his numerous love affairs-can make him forget his virtue. Apollo's wits are befuddled by Bacchus. Mercury, god of commerce and temperance, evens out the extremes of good harvest and bad, and winter and summer, caused by the changing moods of Ceres. Hercules may be the stongest, bravest man in the world, but small, weak Eros is said to be the most powerful of the gods, to whom even Zeus submits.

In the other set of oppositions, Juno's advocacy of advantageous marriages is balanced by Athena's virginal disdain for submitting to anyone except her father. For nature’s bounty, do we go to the sea or the mountains, the bounty of Diana's quiet forests or of Neptune's turbulent waters? Quiet Vestia and her virgins stick to their hearth while Mars is out conquering the world. Aeolus gives Odysseus a fair wind as long as he keeps the other winds under wraps and his men aren't disloyal; Daphne suffers from others' inability to keep their impulses at bay, but is faithful to herself.

Armed with such contrasting pairs, players of the game could learn lessons in both morality and Greek mythology. Depending on the sequence of the cards in playing a trick-taking game, they could also develop other contrasts from other characteristics of these gods. Whatever helped a player to remember what cards had been played, in the Art of Memory in which all public speakers and children of the nobility were schooled, could have been brought to bear.

SOURCES FOR AEOLUS

I had a hard time contrasting Daphne with Aeolus as Fame, as opposed to Aeolus as benefactor to Odysseus. In the latter capacity he is both the source of riches, for one who knows how to sail by the winds, andt a tester of Odysseus’s men. Greed and lack of loyalty to their captain contrasts with Daphne’s loyalty to herself against Apollo’s uncontrolled desire. Aeolus as Fame seems to me, as it would have to the Milanese humanists, a medieval confusion, whereas Aeolus as keeper of winds is the ancient account that theyi would have favored. I will elaborate.

What I think is the most relevant story about Aeolus is in the Odyssey, Book X:

(

http://www.theoi.com/Titan/Aiolos.html). Odysseus is speaking:

“…He [Aeolus] gave me a bag made from the hide of a full-grown ox of his, and in the bag he had penned up every Wind (anemos) that blows whatever its course might be; because Kronion [Zeus] had made him warden of all the Winds (anemoi), to bid each of them rise or fall at his own pleasure. He placed the bag in my own ship’s hold, tied with a glittering silver cord so that through that fastening not even a breath could stray; to Zephyros (the West Wind) only he gave commission to blow for me, to carry onwards my ships and men. Yet he was not after all to accomplish his design, because our own folly ruined us.

For nine days and through nine nights we sailed on steadily; on the tenth day our own country began to heave in sight; we were near enough to see men tending their fires on shore. It was then that beguiling sleep surprised me; I was tired out, because all this time I had kept my own hands on the steering-oar, never entrusting it to one of the crew, for I wished to speed our journey home. Meanwhile the crew began murmuring among themselves; they were sure I was taking home new presents of gold and silver from Aiolos…

Thus the men talked among themselves, and the counsels of folly were what prevailed. They undid the bag, the Winds (anemoi) rushed out all together, and in a moment a tempest (thuella) had seized my crew and was driving them--now all in tears--back to the open sea and away from home…”

Aeolus as controller of the winds also occurs in Book I of the Aeneid, this time acting on the bidding of Juno against Aeneas:

“[50] Thus inwardly brooding with heart inflamed, the goddess came to Aeolia, motherland of storm clouds, tracts teeming with furious blasts. Here in his vast cavern, Aeolus, their king, keeps under his sway and with prison bonds curbs the struggling winds and the roaring gales. They, to the mountain’s mighty moans, chafe blustering around the barriers. In his lofty citadel sits Aeolus, sceptre in hand, taming their passions and soothing their rage; did he not so, they would surely bear off with them in wild flight seas and lands and the vault of heaven, sweeping them through space. But, fearful of this, the father omnipotent hid them in gloomy caverns, and over them piled high mountain masses and gave them a king who, under fixed covenant, should be skilled to tighten and loosen the reins at command.” (

http://www.theoi.com/Text/VirgilAeneid1.html)

Aeolus is like the pilot who knows how to use the winds to his advantage. The winds are compared to wild passions, such as that with which Cupid afflicted Apollo for Daphne, but which followers of Aeolus will master.

But what about the other alternative, that Aeolus was meant as Fame, the trumpeter of Renown to all lands, and the bringer of riches by others’ association with the one so graced? Here is what one scholar observes about Eolus:

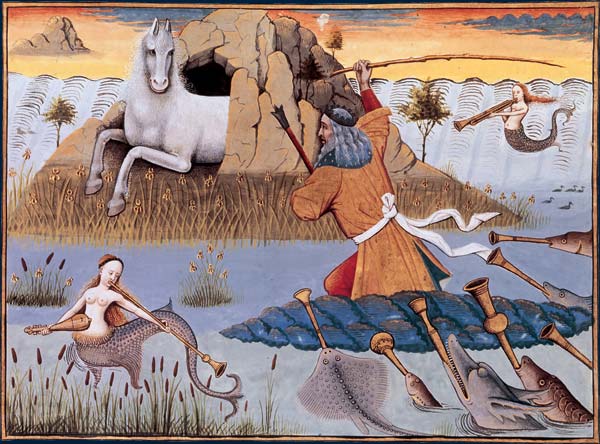

“In medieval iconography Aeolus was represented blowing two trumpets, as in a miniature in a manuscript of Fulgentius Metaforalis (c. 1331), by John Ridewall (Panofsky, Plate XIII). There Aeolus blows two trumpets while working a pair of bellows with his feet. The trumpets and bellows are briefly described by Albericus Philosophus, De deorum imaginibus libellus XIII (1342). The trumpets of Fame appear in Gower's Mirour de l'omme, 22129-22152.” (

http://www.columbia.edu/dlc/garland/dew ... /eolus.htm)

Gower’s poem was written 1376-1379. in Old Anglo-French. I have tried my best to render the basic sense of the two stanzas:

Fortune, tu as deux nacelles

Pour toy servir, si volent celles

Plus q’arandelle vole au vent,

So portont de ta court novellas;

Mais s’au jour d’ey nous porent belles,

Demein les changont laidement:

L’une est que vole au noble gent

C’est Renomee que bell et gent

D’onour les contes les favelles,

Mais l’autre un poy plus asprement

So vole, et ad noun proprement

Desfame, plaine de querelles.

C’est duy par tout u sont Volant

Chascune entour son coil pendant

Porte un grant corn, don’t ton message

Par les paiis s’en vont cornant.

Mais entrechange nepourqant

Souvent faisont de leur cornage,

Car Renome, q’ier vassellage

Cornoit, huy change son langage,

Et d’autre corn s’en vait sufflant,

Qu’est de misere et de hontage:

Sique de toy puet ester sage

Sur terre nul qui soit vivant.

Fortune, you have two baskets

To serve you, which fly

More than tassles fly in the wind,

So they appear like your court novellas;

If yesterday they appeared beautiful to us,

Tomorrow they appear ugly:

The one, which flies to a noble race,

Is Renown, whose tales favor

Beauty and people of honor,

But the other one a bit more disparagingly

Flies, and to none properly

Of fame, but is full of quarrels.

It is from you that all are Flying.

Each, hanging around its neck,

Carries a great horn, sounding

Your message into the lands.

But nonetheless, they often make an exchange,

Because Renown, which yesterday the horn served,

Today changes its language,

And the other horn sounds there instead,

That of misery and shame:

Who is wise to you?

On earth nothing that is alive.

(Complete works of John Gower, vol. 1 p. 248, at Google Books)

But this is only about Fame, Fortune, and the wind; Aeolus is not mentioned.

Oddly enough, just before this passage is what must be one of the earliest references to playing cards in England. I do not recall its being included on the playing card history sites:

“La dee du quell tu juerez

Ore est un siaz, or est un as… (22002ff)

The goddess with whom you play

Now is a six, now an ace… (p. 247)

In another work Gower does speak of Eolus (

Confessio Amantis, 2:4:731ff, at

http://www.library.rochester.edu/camelo ... av2b4t.htm) . In this tale, which I have not seen elsewhere, one of his daughters becomes pregnant by one of his sons. He has the daughter killed. Could that be the reference? It parallels Daphne’s fate, but it is hardly a tale about riches.

Before Gower there was Chaucer, in his

House of Fame, written in Middle English (here modernized):

“And at that she [Persephone?] summoned her messenger who was in the hall, and bade him, on pain of blinding, to go speedily and summon Aeolus, the god of winds: 'ye shall find him in Thrace, and bid him bring his clarions, that be full diverse in their tone. That is called Clear Laud with which he is wont to herald them that I please to have praised; and also bid him bring his other clarion, which everywhere is called Slander, with which he is wont to dishonor them that I will, and to shame them.'” (

http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~amtower/HOUSE.HTM)

Did the Milanese know these English sources? I am skeptical. How would they have known them, or Chaucer’s English? They were busy rediscovering the classical past. But were there such references in medieval Latin sources? I have looked in books discussing Chaucer’s sources. Piero Boitani

(

Chaucer and the imaginary world of fame, p. 165, at Google Books) observes that one “might have been the Christian commentator Bernardus Sylvestrus, for whom Aeolus meant “glory” and was associated with the “sapientia” of Odysseus, “because all science has its beginning in glory”; and Aeolus’s son is said to come from Aeolus “because the vain love of praise swells up a windy voice.”

As far as Albricus Philosophius, in his treatise entitled

De Deoum Imaginibus, this English writer, according to the 19th century scholar identifying him as a possible source, is extremely obscure, not listed in any book of English biographers (

Studies in Chaucer, Vol. 2, by T.R. Lounsbury, at Google Books.) It is clear in Lounsbury that there are two trumpets, but not what they are used for.

These sources, still mostly English, do suggest the possibility that there was a common understanding that Aeolis/Eolis blew the trumpets of Fame and Scandal. The Milanese thus could conceivably have associated Aeolus with Fame.

But barring some reference of which I am aware, it still seems that the

Odyssey is a far more likely source. There are two others in Latin that may help to diffuse the doubt: Virgil’s

Aeneid again and Ovid’sMetarmorphoses. In Virgil, I have found one more reference, besides that in Book I to Aeolis as the keeper of the winds; the other is in Book VI. This later book would have been read closely in Milan at this time because the humanist Decembrio, one of the commentators on the Michelino, in 1419 wrote a continuation of the Aeneid, which he called “Book XIII” (

http://www.virgil.org/supplementa/decembrio.htm); it was only 89 lines, but it may have inspired a longer “continuation” in 1428 by another humanist, which Decembrio considered “plagiarism).

In Book VI we read:

“And as they came, they see on the dry beach Misenus, cut off by untimely death – Misenus, son of Aeolus, surpassed by none in stirring men with his bugle’s blare, and in kindling with his clang the god of war. He had been great Hector’s comrade, at Hector’s side he braved the fray, glorious for clarion and spear alike; but when Achilles, victorious, stripped his chief of life, the valiant hero came into the fellowship of Dardan Aeneas, following no meaner standard. Yet on that day, while by chance he made the seas ring with his hollow shell – madman – and with his blare calls the gods to contest, jealous Triton, if the tale can win belief, caught and plunged him in the foaming waves amid the rocks.” (

http://www.theoi.com/Text/VirgilAeneid6.html)

And here is Ovid, Metamorphoses XIV, 101ff:

“When he had passed those islands, and left the walls of Parthenope behind him to starboard, the tomb of Misenus, the trumpeter, the son of Aeolus, was to larboard, and the shore of Cumae, a place filled with marshy sedges.” (

http://etext.virginia.edu/latin/ovid/tr ... orph14.htm)

It is Misenus, not Aeolus himself, who is the trumpeter. For these early humanists, it was important to get one’s classical sources accurate and not rely on careless medieval sources (see Wikipedia, Renaissance Humanism). If anyone meant Aeolus’s son, they would likely have said as much. I conclude—again, barring information I may have missed--on several grounds, that the Aeolus of

Odyssey Book X is the likeliest candidate for the Aeolus of the Michelino.