The significance includes early French and Imperial influence on the Visconti and their initiation of 'paraheraldry' - imprese - in regard to madrigal poetry here. What is unclear to me as to why the eagle (often conflated with the significance of the dove here) didn't maintain a more pronounced status under Filippo, but note the emblem of Pavia (and all Visconti dukes are first Counts of Pavia when younger) is three stacked eagles. I suppose its imperial meaning was enough, but if the family was so identified with two birds early on its easy to see why Marziano features suits of birds. The other main take away is that their primary symbols were created in the context of a wedding (for which I associate the CY). Finally the references to "three orbs" seems to be a precursor to the three interlocked rings.

Perhaps the most illuminating research on the Visconti heraldry I've read (her frequent references to Kirsch I've largely left out as they are well known here), especially since it discusses its genesis; excerpts from Chapter 4 (pp 122-144), but first the abstract:

Abstract: This study investigates a repertoire of eighteen madrigals whose texts refer to heraldry, all of

which were composed in trecento Italy. The hereditary and personal arms cited in the song texts

are those of the Visconti, Della Scala and Carrara families of northern Italy. Though these

madrigals have been used in the past as a means for dating manuscripts and reconstructing

composer biographies, they have never been studied as a discrete repertoire. This study applies

musicological, heraldic and art historical approaches to the repertoire in order to investigate the

heraldic madrigal as a manifestation of political authority in trecento Italy.

A Trinitarian Reading of Jacopo da Bologna’s Aquila altera

Despite being one of the most extraordinary songs of the heraldic madrigal repertoire, Jacopo da

Bologna’s three-voice madrigal Aquila altera/Creatura gentile/Uccel di Dio continues to be

ignored by both musicologists and performers. As is the case with most heraldic madrigals,

musicologists have only been interested in using the heraldic references in Aquila altera to

reconstruct the biography of Jacopo da Bologna. I believe, however, that a thorough study of the

heraldry in Aquila altera can tell us much about the occasion of its performance, the relationship

between Jacopo da Bologna and members of the court of Galeazzo Visconti, and finally, how

unusual madrigals such as Aquila altera were perceived by scribes and collectors of trecento

song.

Nino Pirrotta was the first to suggest a date for Aquila altera, proposing that it had been

written to celebrate the visit of emperor Charles IV to the Visconti court in 1354.335 Geneviève

Thibault thought otherwise: she believed it more likely that Aquil’altera had been written in

1360 on the occasion of Giangaleazzo Visconti’s wedding to Isabelle de Valois, daughter of the

French king John II.336

In Thibault’s interpretation, each stanza of the madrigal mentions a

heraldic badge, either of the Visconti or the Valois: the upper voice sings of the eagle, the middle

voice mentions the sun, and the lower voice describes the “Bird of God”, which can be

interpreted as both the eagle and the dove. The eagle is an emblem of the Visconti, reflecting

their status as imperial vicars, and is also reminiscent of John the Evangelist, revealer of the

Trinity. The dove-in-sun badge is said to have been adopted by Giangaleazzo when he married

Isabelle. This chapter will show that heraldic references within the song, as well as their

trinitarian associations, strongly suggest that Thibault’s theory is correct.

The Paraheraldry of Giangaleazzo Visconti

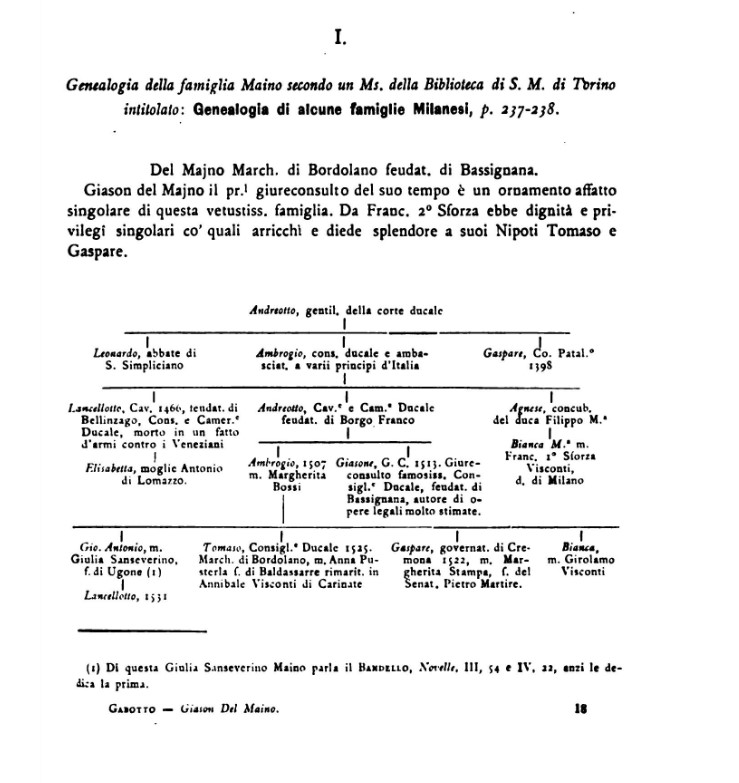

The Visconti arms were the same as those of Milan: a blue viper or biscia, said to be that of St

Ambrose, holding a red human figure in its mouth (Figure 3.1)337. Because the biscia charge was

associated with the lordship of Milan (which was held by his uncle Bernabò), Giangaleazzo

Visconti did not adopt it until after his takeover of Milan in 1385. When Giangaleazzo became

Duke of Milan in 1395, his arms were changed to reflect his new status: the biscia was now

quartered with the imperial eagle.338

In addition to their official heraldry, the Visconti were among the first Italian noble

families to adopt paraheraldic devices, a practice that seems to have originated with

Giangaleazzo’s father Galeazzo II.339 Though we do not know exactly when, Galeazzo adopted

the divisa dell’acqua e del fuoco, the device of water and fire, consisting of “a ragged staff set

diagonally, burning at its lower end and supporting at its upper end two pails of water suspended

from the same rope.” 340 The taste for paraheraldry was passed on to Galeazzo’s son

Giangaleazzo, and also to Giangaleazzo’s son Filippo Maria, who adopted the paraheraldic

devices of both his father and grandfather.341 Thus, along with true heraldry, Visconti

paraheraldry was passed on from generation to generation.

...

The paraheraldic badge most commonly associated with Giangaleazzo, however, is that

of the dove in the sun, featuring a white dove set against the rays of the sun with blue sky in the

background, and sometimes accompanied by the motto A bon droit. This device is often thought

to have been created by Petrarch and based on the heraldry of Isabelle de Valois, to whom

Giangaleazzo was married in October 1360.352 This connection with Giangaleazzo’s marriage

explains why the dove-in-sun badge is also associated with his epithet, Conte di Virtù, since part

of Isabelle’s dowry was the county of Vertus in France (which was Italianized as Virtù, meaning

virtue).

In his canzona Pascolando mia mente al dolce prato, Petrarch explains the dove-in-sun badge.

The sun represents the lord’s power, and its rays of unequal length reach out to everyone, so that

their souls can be bathed in its light.353 The dove symbolizes chastity and humility, the sky

stands for serenity, and three orbs or balls (palle), which may be on the dove’s chest or on the

sun, signify lawfulness, loyalty and honesty.354 Writing in 1389, Visconti court poet Francesco

di Vannozzo expands on Petrarch’s poem in his Canzon morale fatta per la divisa del conte di

Virtù (Moralizing Song Made on the Device of the Count of Virtù). The sun, symbol of

Giangaleazzo, is discussed first:

Per sua divisa al tuo signor è dato | Your lord is given for his device

un sol, che rappresenta sua persona | , a sun, representing his person,

in segno di corona | in the shape of a crown

tra gli altri e de victoria trionfante…| triumphant in victory among all others…

Mira gli raggi suoi che dan splendore | Admire the sun’s rays that give brightness

tramegg’i grandi, maggi e piccolini: | among them the large, the medium and the very small:

questo vuol ch’endovini | you are meant to realize

che del suo lume ogn’anima è vestita...355 | that from its light every soul is clothed…

The next element Vannozzo describes is the dove, which symbolizes humility:

…

ziò che comprende l’alba totorella, | that which comprises the white dove

la qual con Umeltà tanto s’inbella | that which with Humility beautifies itself so much

a Purità conzonta e Castitate; | combined with Purity and Chastity;

chè se con lui legate | so that linked to it

seran queste tre donne356 | will be these three women

Finally, Vanozzo discusses the blue background, home of the sun:

Apri la luce ancora e poni mente | The light opens and reminds us

al chiaro sole che non alberga in valle;| that the bright sun that does not sleep in valleys;

ma con soe dolce spalle | but with its sweet shoulders

riposa e giace ne l’azurro cielo,| rests and idles in the blue sky,

de cui color risorge a tutta gente | the colour of which reminds everyone

tre zentilesche e lizadrette palle, | of three noble and beautiful orbs,

che saglion come galle| that rise like floats

riempiendo il mondo d’amoroso gielo. | filling the world with loving cold.

Vannozzo then summarizes this device in trinitarian terms. The azure background symbolizes

heaven (the “loco del padre”), the sun represents Christ and the dove embodies the Holy Spirit:

Prima l’azurro per lo ciel si pone,| First the blue stands for the sky,

eterno loco d’un Padre da cui | eternal realm of a Father from whom

el sol Figlio, per cui | comes the only Son, through whom

se tien lo mondo franco; | holds the mortal world;

poi l’ucel bianco, Spirito Santo, in quale | then the white bird, Holy Spirit, on whom

s’apoggia per salvarse ogni mortale.357 | every mortal depends for salvation.

....

As we have seen, Giangaleazzo’s dove-in-sun badge, most probably created on the

occasion of his marriage to Isabelle de Valois in 1360, is the paraheraldry most often associated

with him, and the one most often used to link his religious and dynastic concerns.364 In Five

Illuminated Manuscripts for Giangaleazzo Visconti, Kirsch argues very convincingly that two of

these manuscripts, Lat. 757 and Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Smith-Lesouëf 22,

commemorate the marriage of Giangaleazzo to his cousin Caterina in 1380 and demonstrate

Giangaleazzo’s “lifelong devotion to both the Holy Ghost and the Trinity.”

365 While the two illuminated manuscripts are the earliest examples of the artistic depiction of the dove-in-sun

device, Jacopo da Bologna’s madrigal Aquila altera/Creatura gentile/Uccel di Dio can be

considered the first musical work to refer to this device. 366....

Aquila altera/ Creatura gentile/Uccel di Dio

Aquila altera, ferma in su la vetta Heavenly eagle, lift the valorous eye

de l’alta mente l’occhio valoroso, above the summit of the high mind,

dove tuo vita prende suo riposo, where your life takes its repose,

là è’l parer e là l’esser beato. There is the appearance and there bliss.

Creatura gentil, animal degno, Gentle creature, worthy animal,

salire in alto e riminare’l sole only to rise high and look at the sun

singularmente tuo natura vole. your nature flies.

Là è l’imagine e là perfezione. There is the image and there, perfection.

Uccel di Dio, insegna di giustizia, Bird of God, emblem of justice,

tu hai principalmente chiara gloria, you have above all clear glory,

perché ne le grand’opre è tua vittoria. because in great works is your victory.

Là vidi l’ombra e là la vera essenza. There I see shadow and there the true essence.

The madrigal Aquila altera/Creatura gentile/Uccel di Dio features three voices, each singing a

different text. Each voice mentions a heraldic device associated with Giangaleazzo Visconti: the

cantus sings of the eagle, the middle voice refers to the sun, and the tenor sings of the Bird of

God, which could refer to the dove, or again to the eagle. Although one of the most original

madrigals written before French music became popular in Italy, Aquila altera has been all but

ignored. This may be due in part to Pirrotta’s assumption, unlikely as it seems, that the madrigal

is missing both the second tercet of the poetry and the second line of text in the ritornello, in all

surviving versions.367 While it is improbable that there is text missing, the poetry of Aquila

altera is certainly unique. As we have seen, most madrigal texts consist of two tercets made up

of eleven-syllable lines, and a two-line ritornello. Aquila altera, however, is made up of three

tercets (one for each voice) and a one-line ritornello for each voice. Each tercet is constructed in

the same way: the first line describes a bird who embodies a virtuous attribute (“heavenly,”

“gentle,” “worthy,” “just”). The second line of each tercet associates the bird with physical or

metaphorical height (“fix the gaze of the high mind,” “only to rise high and look at the sun,”

“you have above all clear glory”). Finally, each ritornello is related to the others by means of

similar formal structure and through the comparison and juxtaposition of similar concepts

(appearance/image/shadow vs. heavenly existence/perfection/true essence).

....

In her groundbreaking article “Emblèmes et devises des Visconti,” however, Geneviève

Thibault pointed out that the heraldry in the madrigal’s text makes more sense if we consider that

the song had been composed in 1360 for the wedding of Giangaleazzo Visconti to Isabelle de

Valois, daughter of the French king John II (sometimes called “the Good”).

384 Thibault reasoned that since we know that Jacopo had been in the service of Luchino Visconti, it would be

reasonable to look for Visconti devices in the text of Aquila altera. This led to the discovery

what she believed were three heraldic or paraheraldic charges of the Visconti in the madrigal

text: the eagle, while technically not a Visconti heraldic charge at that time, represented the

family’s role as imperial vicars, and the dove (Uccel di Dio, “Bird of God”) and the sun were

part of the paraheraldry of Giangaleazzo, and seemed to have some connection to his wife,

Isabelle.385

More recently, Oliver Huck has reiterated Thibault’s theory, but interprets creatura

gentil as representing the union between Giangaleazo and Isabelle itself.386

The reference to the Bird of God in the madrigal’s text is confusing, since we naturally

assume that this represents the dove of the Holy Spirit, but in medieval Italian literature the Bird

of God clearly refers to the eagle.387 There is no real need, however, to choose between the two,

if we keep in mind that medieval readers were not overly worried about polytexuality,

intertextuality or the exact intentions of the author. With regard to medieval symbols, Russell

Peck states “One does not ask… ‘What does it mean?’ Rather one asks ‘What can it mean?’.”

388 In this case, I believe that the Bird of God can be taken to mean either the eagle, who is

described by the other two voices in the song, or the dove, implied by the other trinitarian

associations of the music and text, reflecting Giangaleazzo’s badge. Instead of simply relying on

the openness of medieval interpretation to associate Giangaleazzo with Aquila altera, however,

there are other reasons to suppose that the madrigal was composed for the wedding of

Giangaleazzo and Isabelle de Valois. If Giangaleazzo’s connections to the text of Aquila altera

can be doubted on heraldic grounds, Isabelle’s cannot. As a member of the French royal family,

Isabelle’s heraldry was the royal fleur-de-lys, which the house of Valois had taken great pains to

associate with the Trinity.

...

If Jacopo da Bologna wanted to celebrate Giangaleazzo’s marriage and the adoption of

the dove-in-sun badge, why did he not refer to either the badge or the fleur-de-lys explicitly in

the text? Why do all three voices sing about the eagle instead? (although, as mentioned above,

the tenor sings about the Bird of God, which can be interpreted as the eagle and/or the dove). Do

the answers to these questions exclude Giangaleazzo as the patron, or his wedding as the event

for which Aquila altera was composed? Obviously, I will argue that this is not the case at all. In

1360 Giangaleazzo’s father Galeazzo was granted an imperial vicariate, so we can assume that

the presence of the eagle in the text of Aquila altera is designed to impress Galeazzo’s new

political status upon those who would have heard the madrigal. And apart from the textual

references that suggest a trinitarian reading of the song, the formal structure of the music lends

itself to a such a reading, and also to such a hearing, since the madrigal is for three voices, with

different but related texts for each voice. Each voice, while part of a unified whole, is able to

present a different version of the same story. Although this is perhaps far-fetched, it is also

possible to interpret the canonic form of the madrigal in trinitarian terms: the secundus flows or

follows directly from the cantus, whose musical material it imitates, suggesting the relationship

between two persons of the Trinity, the Father and the Son.

...

Conclusions

When we consider the evidence given by the trinitarian associations of the dove-in-sun badge

and the lilies of the Valois, then, it seems very likely that Thibault’s theory is correct, and Aquila

altera was indeed commissioned for Giangaleazzo’s wedding in 1360. The hypotheses of Corsi

and Pirrotta do not acknowledge the reference to the sun in the second tercet of the madrigal, and

can therefore be discounted.

...

Giangaleazzo and Isabelle were married in Milan in October 1360. The bride was eleven

years old and the groom had just turned nine. Three contemporary accounts exist of the wedding.

The chronicler Pietro Azario limits his discussion of the marriage to the amount spent by

Galeazzo to procure the bride, 409 but Matteo Villani, brother of the Florentine chronicler

Giovanni Villani, gives much more detail. Though highly biased (he complains that while the

French king received three hundred thousand scudi, all he gave in return was the “tiny county of

Vertus” 410), he describes the wedding negociations, preparations and festivities. The event

Villani describes was certainly extravagant, the Lords of Milan having collected jewels, precious

stones and fabrics with which to make clothing and other decorations.411 The celebrations lasted

for three days, and included jousts and a feast for more than a thousand featuring Lombard

specialities.412 Heraldry was everywhere, because the “festivities were of the most noble kind”

and the guests had to be made to appreciate this.413 Finally, it seems as though the festivities

included dancing: two instrumental dances, named Isabella and Principio di Virtù, were almost

certainly composed for this event.414

Two further points should be made with regard to Aquila altera. First, since

Giangaleazzo was only nine years old at the time of his marriage to Isabelle, the commission for

Aquila altera must have originated with his father, Galeazzo. Therefore, the trinitarian references

in the song’s text and music are a clever way for the composer and poet (or composer/poet) to

acknowledge both the support of the father (Galeazzo) and the marriage of the son

(Giangaleazzo).

...

The second point I would like to mention concerns the imperial vicariate granted to

Galeazzo that same year, which is represented by the eagle in the song text, though this

obviously stands for John the Evangelist as well. The presence of the eagle/imperial vicariate

reference is especially important since it was primarily his wealth, and not his political influence,

that had allowed Galeazzo to marry his son into the French royal family.418 It seems perfectly

plausible, therefore, that Galeazzo would want to show off his newly acquired title as a rebuttal

to those who had accused him of buying himself an undeserved royal daughter-in-law.

In summary then, Jacopo da Bologna’s madrigal Aquila altera/Creatura gentile/Uccel di

Dio features an unusual textual and formal design, which, I have argued, is due to the occasion

for which it was written. Each heraldic element mentioned in the text refers to Giangaleazzo

Visconti and his devotion to both the Holy Spirit and the Trinity. If we accept that the dove-in-sun emblem was created on the occasion of Giangaleazzo’s marriage in 1360, then Aquila altera is the first artistic work to document Giangaleazzo’s adoption of the device, and we can even consider the possibility that Aquila altera was meant as much as a celebration of his new

paraheraldry as it was a commemoration of his wedding. It is unfortunate that this heraldic

madrigal has been ignored for so long, since it reveals so much about fourteenth-century

perceptions of the relationships among concerns for piety, dynastic ambition and personal identity.